[ad_1]

Hiram Dryer is not a name that readily comes to mind when we ponder leaders who stood out during the Battle of Antietam. He remains largely unknown to all but the battle’s most ardent students, yet the impact Captain Dryer had on the fighting September 17, 1862, should not be underestimated.

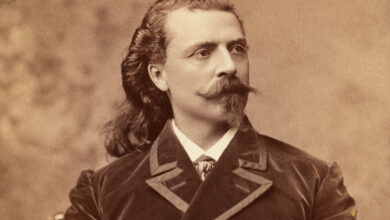

A New York native, Dryer was 53 years old at Antietam. Relatively little is known about his early years, but on October 1, 1846, during the Mexican War, he enlisted in the Regular Army. Assigned to the newly organized Regiment of Mounted Riflemen, he rose rapidly in rank to first sergeant, and then earned a commission on July 31, 1848, as a second lieutenant in the 4th U.S. Infantry for gallantry at the battles of Chapultepec and Garita de Belan. He served for a time with future Civil War luminaries Ulysses S. Grant, Phil Sheridan, and George Crook. In 1852, the 4th U.S. was transferred to the West Coast, which required the regiment first to cross the Isthmus of Panama and then journey by ship to the Pacific Northwest. Passage across Panama’s isthmus was a nightmare, as a cholera breakout killed 104 enlisted men and one officer. In November 1853, while stationed at Fort Vancouver in Oregon, Dryer displayed trademark courage in volunteering to lead a supply expedition to a group of settlers trapped by a blizzard in the Cascade Mountains.

(University of Washington libraries, special collections, POR2041)

Dryer returned with his regiment to the East in the fall of 1861 and was assigned to the Army of the Potomac. The early war period was a time of great change for the Regular Army, its leadership decimated both by officers assuming commissions of higher rank in the U.S. Volunteer service and Southern-born officers who resigned to fight for the Confederacy. Individuals pulled from civilian life frequently filled the resulting vacancies.

The enlisted ranks were also in flux due to the expansion of the Regular Army, featuring nine new regiments of infantry and one each of cavalry and artillery. Some of the noncommissioned officers serving under Dryer were no doubt grizzled veterans, but many of his soldiers had enlisted in 1861. Rigorous training and discipline was what set Regulars apart from most volunteer regiments, and the heightened attention they received in skirmishing and marksmanship would prove particularly crucial.

Dryer, who saw service during the 1862 Peninsula and Second Bull Run campaigns, was his regiment’s senior officer when fighting broke out at Antietam. At about 10 a.m. September 17, Maj. Gen. George McClellan ordered his cavalry commander, Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, to cross Antietam Creek at the Middle Bridge with his troopers and horse artillery in order to provide a diversion and support to the current Union attack on the Confederate position along the Sunken Lane.

A diversion was a sound idea; using cavalry was not. Most Union troopers lacked carbines or training in fighting dismounted, so Pleasonton’s men were forced mainly to hide from enemy artillery either behind Joshua Newcomer’s large barn or on the Antietam Creek bank. This left the horse artillery exposed to long-range fire from skirmishers and sharpshooters. Disgusted that his guns and the others had been sent into harm’s way without proper support, one horse battery commander, John C. Tidball, sought infantry help.

Pleasonton managed to get two companies of the 1st Battalion/12th U.S. Infantry (1/12th) to support his batteries, and then for Brig. Gen. George Sykes, commanding the 5th Corps’ 2nd Division (which included all of the army’s Regular regiments) to send in the entire 2nd/10th U.S. Infantry, commanded by Lieutenant John Poland.

Fierce artillery duels and skirmishing continued well into the afternoon. Worried the Confederates had large reserves concealed behind Cemetery Hill and Cemetery Ridge, Sykes was reluctant to send more infantry across the creek but acquiesced on Poland and the 2nd/14th U.S., and then, at 2 p.m., ordered Dryer to cross the creek with the 4th U.S. and the 1st/14th U.S. and to assume command of all Regular forces there.

Described by a peer “as one of the coolest and bravest officers in our service,” Dryer proceeded to justify such high praise. He first reinforced the Regulars’ skirmish line west of Newcomer Ridge—high ground several hundred yards west of the Newcomer farmhouse. Then, he ordered skirmishers forward on both sides of the Boonsboro Pike, toward Cemetery Hill south of the pike, and Cemetery Ridge, north of it. Unlike commanders who liked to test enemy strength and position by an all-out attack with massed infantry, resulting in extensive casualties—Maj. Gen. William H. French, for instance—Dryer used the superior training, leadership, and marksmanship of the Regulars to probe and press the enemy defenses, his men deployed in dispersed order, offering no inviting targets for Confederate artillery or riflemen.

Backed by plentiful artillery deployed along Newcomer Ridge, the Regulars worked their way forward, advancing on the left as far as the Sherrick Farm lane and on the right, north of the pike, using four companies (at most 130 men) to dislodge Confederate defenders on Cemetery Hill. While forcing the artillery there to withdraw, they advanced within 450 yards of the Lutheran Church on Cemetery Hill’s western slope. But that would be their high-water mark, not because of Rebel resistance, but because of General Sykes. What Sykes saw in Dryer’s advance was an unnecessary risk rather than an opportunity. He found it highly unlikely the Confederate center was simply a hollow shell, only that his Regular infantry faced potential destruction with Dryer exceeding his orders.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Sykes’ orders directing him to immediately withdraw his forces to Newcomer Ridge left Dryer incredulous. Asking if there was any discretion, he was told the “order was imperative.” Gathering up their dead and wounded, Dryer and his Regulars fell back.

At a cost of 11 killed and 75 wounded, they had cleared Cemetery Ridge of Confederates and threatened to capture Cemetery Hill. It would be an exemplary yet virtually unknown achievement. When one considers that the 1st Delaware lost 230 men alone in French’s failed frontal assault upon the Sunken Lane, Dryer’s proficiency in tactics and managing his troops is remarkable.

Dryer went on to receive brevet promotions for courage at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville but, surprisingly, not for Antietam. He apparently lacked political clout, or had no interest in taking a volunteer commission, for there is no evidence he sought or was considered for promotion to higher rank in the volunteer service.

Thrown from a horse in June 1863, Dryer would miss the Gettysburg Campaign. The injury apparently affected his ability to return to the field, for he spent the rest of the war in staff duties. He was remembered by a fellow officer as “always kind and friendly.” We might add that he was also a man of remarkable, daring skill and competence who deserves to be remembered.

[ad_2]

Source link