[ad_1]

(Watch an interview with author John C. McManus here.)

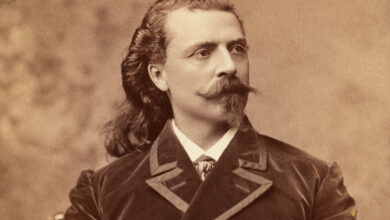

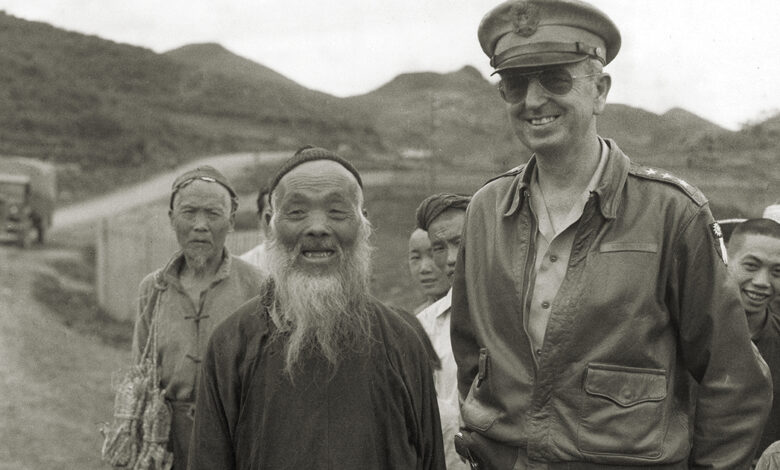

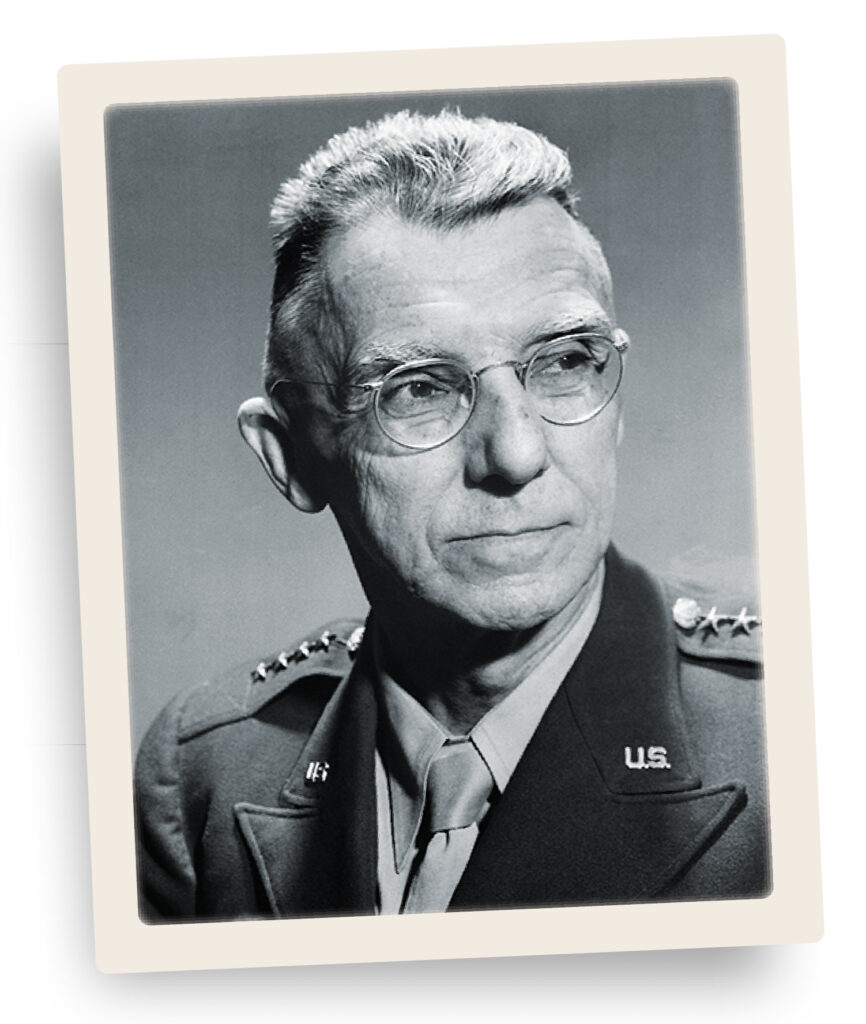

Major General Albert Wedemeyer was a difficult man to surprise, but he knew that war often confounded the predictable. Born to German American parents in Nebraska, fluent in the tongue of his ancestors, and one of the U.S. Army’s few graduates of the Kriegsakademie, Germany’s war college, he did not expect to succeed General Joseph Stilwell in China. The news of this had come to Wedemeyer in the form of an urgent message from Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall on the evening of October 27, 1944, just as Wedemeyer drifted off to sleep in his bunk at Kandy on the island of Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka). At the time, Wedemeyer served as deputy chief of staff to Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, the British commander of South East Asia Command, the polyglot theater that included Burma and India.

Tall, stately, impeccably groomed and neatly coiffed, Wedemeyer’s pleasing physical appearance accurately suggested a man more at ease in a boardroom than a foxhole. A 1919 West Point graduate with two and a half decades of loyal service, he had no combat experience, little command time, and almost nothing in common with the average soldier. Clever, diplomatic, and adept at under-the-radar self-promotion, Wedemeyer counted himself among George Marshall’s many protégés. He also found an influential sponsor in Lieutenant General Stanley Embick, whose daughter Elizabeth he had married in 1925. Wedemeyer clearly lacked the inspirational characteristics of a frontline commander.

Much more a manager than a leader, Wedemeyer’s understanding of modern combat tended more toward the intellectual than the experiential. But he possessed an incisive strategic mind, one that marked him as an insightful military thinker who was blessed with a strong understanding of geopolitics. On the eve of the war, when Wedemeyer was only an overaged major in the War Plans Division at the Pentagon, an organization his father-in-law had recently commanded, Marshall had chosen him to work on a team to produce a comprehensive plan for mobilization and victory when the United States entered the conflict. Wedemeyer’s significant contributions to this so called “Victory Plan” had circuited his career in a relentlessly upward direction, with a rapid two-year rise from major to major general, and led historical posterity, with his gentle prodding, to afford him a bit too much credit for the plan’s success. For the first two years of the war, Wedemeyer had remained part of the War Plans Division, functioning as a roving planner and consummate military insider, and an intimate participant in high-level conferences from London to Casablanca and Washington, D.C., helping to craft Allied grand strategy. He emerged as one of the army’s leading experts on German military capabilities, a skill set that he expected—incorrectly, as things turned out—would lead him to spend the war in Europe. He argued passionately for a cross-channel invasion of France in 1942 and 1943, butting heads with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who advocated successfully for Mediterranean operations. Wedemeyer’s strategic views were so adamantly opposed to those of Churchill that it was said in high command circles—and Wedemeyer came to believe—the prime minister himself orchestrated his assignment to Mountbatten’s headquarters in October 1943 just to prevent him from having any influence on European grand strategy.

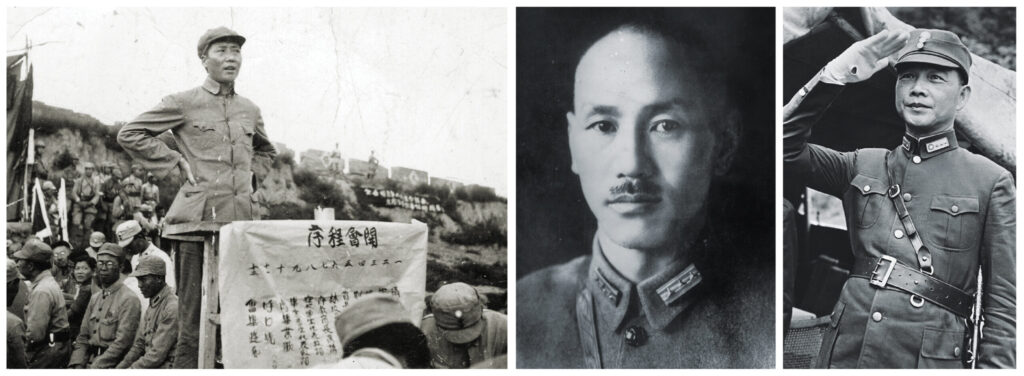

(Left: Hulton Archive/Getty Images; center: Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; right: Bettmann/Getty Images)

If Wedemeyer was something of a map board and typewriter officer, his appointment to China did make some sense in a theater bereft of U.S. ground combat units and where the American military presence never rose above 60,000 soldiers, over half of whom belonged to the Army Air Forces. The situation called for a strategy-savvy military diplomat, not necessarily a warrior. As Wedemeyer served Mountbatten ably for a year, he had observed China’s many problems and Stilwell’s demise, albeit from a distance. Wedemeyer respected Stilwell’s extensive experience on the ground in China and his obvious expertise about the country and its people. But he could not fathom Stilwell’s inability to get along with Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek when the success of his mission, and American strategic aims, so conspicuously depended upon it. Honest and upright, yet prone to small-minded pettiness, Stilwell loved China and its people, but he had grown to detest, in equal measure, Chiang as little more than a third-rate despot and his government as a corrupt, repressive oligarchy with little inclination to fight the Japanese, at least in a manner he thought appropriate. Stilwell’s unvarnished contempt for Chiang finally, in October 1944, exhausted Stilwell’s welcome in China when the Chinese leader demanded his relief after an especially stormy meeting.

These elemental ideas belied the complex realities that actually confronted Wedemeyer when he arrived in China at the end of October. After eight terrible years of war, and the loss of millions of lives, three main power brokers besides the Japanese continued to vie for dominance over a country in which one out of every five people had, at some point, become a refugee. In Japanese-occupied China, the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China under Ching-wei Wang, an ardent follower of the great Chinese nationalist Dr. Sun Yat-sen, saw itself as the best hope to salvage an autonomous China from the ashes of Japanese continental dominance. The Americans and their Chinese allies dismissed this regime as little more than a Japanese puppet (similar to the Allied view of Vichy France). In Yan’an province and nearby portions of northern China, Mao Zedong’s communist shadow government continued to grow in power and influence. Mao now controlled an army of 900,000 soldiers augmented by a similar number of militia and guerrilla fighters. Communist propaganda perpetuated the notion that Mao’s troops were fighting stubbornly and effectively against the Japanese. In reality, they were doing little besides observing mutual back-scratching truces with the Japanese, though communist military formations, by their very existence, did function as an impediment to Japanese influence and expansion in northern China. Instead of fighting, Mao focused on enhancing the political position of his movement and preserving his military strength to fight Chiang and the Nationalists. Both leaders saw the other as the main adversary, far more dangerous than the Japanese and Wang’s so-called puppets; both knew they must one day either destroy or neutralize the other in order to establish real control over China.

(Corbis via Getty Images)

Chiang once opined that the Japanese were like a skin disease, the communists like heart disease. Colloquially known as the “Generalissimo” in acknowledgment of his days as the army’s commander in chief, he remained the face of legitimate public government in China, a flawed but respectable, patriotic figure who had managed to preserve the notion of an independent, modern China through nearly a decade of war. He nominally controlled southern and western China. But his armies were hollow, his government was still plagued by corruption and sapped by the disloyalty of all too many local officials who pursued their own personal agendas, often to the point of defying Chiang’s orders or observing backhanded cease-fire arrangements with the Japanese. The hated foreigners remained in control of Manchuria, the entire coastline, major cities such as Canton and Shanghai, and much of the Chinese heartland. Their ongoing Ichi-go offensive, a massive effort that the Japanese had launched in April 1944, now menaced the eastern frontiers of Nationalist-controlled China, placing the key transit point town of Kweilin in danger as well as perhaps even the Generalissimo’s capital city of Chungking 480 miles to the northwest and the Chinese city of Kunming, a vital supply hub and the location of air bases for American Major General Claire Chennault’s Fourteenth Air Force. Newly established B-29 bases at Chengtu, located some 240 miles northwest of Chungking, were probably well beyond the reach of the invaders, but these fields would inevitably become compromised logistically if the Japanese succeeded in taking any of the other objectives.

Wedemeyer received a multipoint directive from the Joint Chiefs stipulating that his “primary mission with respect to Chinese Forces is to advise and assist the Generalissimo in the conduct of military operations against the Japanese.” He would command all American military forces in the country and serve as Chiang’s chief of staff, as Stilwell had done before him. No doubt with an eye on the looming death struggle for power between Chiang and Mao, the chiefs cautioned Wedemeyer not to let his troops become embroiled in Chinese domestic strife “except insofar as necessary to protect United States lives and property.”

Wedemeyer believed that the key to accomplishing his mission hinged on establishing a good relationship with Chiang. Though Wedemeyer lacked Stilwell’s Chinese linguistic skills, he understood many nuances of Chinese culture, especially the notion of saving face. He had served in China with the 15th Infantry Regiment in the early 1930s and of course learned much during his year on Mountbatten’s staff. He had already met Chiang on several occasions, so he simply built upon the existing relationship. Constitutionally even tempered, the tactful Wedemeyer spoke nary a sharp word to the Generalissimo. He unfailingly treated Chiang with courtesy and respect and the Chinese leader responded in kind. The two men got on well. They met nearly every day, often to discuss the long, thoughtful daily memos that Wedemeyer composed for Chiang.

Wedemeyer sympathetically recognized that Chiang was surrounded by a poisonous coterie of scheming family members, political advisers, and generals who usurped his power and often served as a negative influence. In viewing Chiang as an unrepentant advocate of freedom, though, the American seemed not to grasp the repressive nature of the Nationalist government, at least in the eyes of many Chinese who resented the regime’s confiscatory taxation, its heavy-handed conscription, its wasteful neglect of public health, its inflationary currency, and the tyrannical police state run by the odious but fanatically loyal Lieutenant General Dai Li, Chiang’s right-hand man and intelligence chief. Or perhaps Wedemeyer understood all this well, but diplomatically decided that he must overlook the regime’s flaws in pursuit of a greater good.

Without question the new commander’s genial relationship with Chiang defused some of the tension that had accumulated, like clogged arteries, during the Stilwell years. But Wedemeyer, with his bird’s-eye approach to military life, tended erroneously to equate this with success. “[He] is the kind of man who sees only the great picture, strategy on a global scale,” one of his public affairs officers analyzed confidentially, “but he seems utterly incapable of adjusting his grandiose ideas to practicable conditions and facts. This situation is probably the result of being a ‘book soldier’ with little practical experience.” As General Wedemeyer soon discovered, a nicer work environment could not paper over ugly ground-level realities. An in-depth assessment he sent to General Marshall nearly mirrored many of Stilwell’s reports. “They are not organized, equipped, and trained for modern war,” Wedemeyer wrote of the Nationalist government. “Psychologically they are not prepared to cope with the situation because of political intrigue, false pride, and mistrust of leaders’ honesty and motives. Frankly, I think that the Chinese officials surrounding the Generalissimo are actually afraid to report accurately conditions for two reasons, their stupidity and inefficiency are revealed, and further the Generalissimo might order them to take positive action and they are incompetent to issue directives, make plans, and fail completely in obtaining execution by field commanders.”

(Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Chiang’s underfed, overmatched armies reeled under the weight of a new phase of the Ichi-go offensive, launched by the Japanese in response to China-based raids by American B-29 Superfortresses against southern Japan. The Japanese took Kweilin on November 10, 1944. “The Chinese are not fighting,” a dejected Wedemeyer confided to Major General J. Edwin Hull in one gloomy missive. “It is indeed disconcerting to take over under [these]…depressing circumstances.” For several weeks thereafter, it seemed that the enemy might actually capture Kunming and Chungking, a nightmare scenario that would have compromised the American position in China and might well have destroyed the Nationalist government. “It was highly discouraging when even the highly touted divisions which at great effort we have moved by air or motor transport to the Kweilin-Liuchow area also fell back,” Wedemeyer later wrote.

He found himself in crisis mode, wondering if the military situation was so dire that the Allies might have to choose between hanging on to the cities of Chungking or Kunming. To Army Air Forces Major General Larry Kuter, an old friend, he confided his deep concerns in colorful terms. “I feel that the War Department has made me Captain of a Chinese junk whose hull is full of holes, in stormy weather, and on an uncharted course. If I leave the navigator’s room to caulk up the holes, the junk will end up on the reef and if I remain in the navigator’s seat, the junk will sink.” With admirable resolve, Chiang vowed to stay in Chungking and, if necessary, die there. Wedemeyer made it clear to the Generalissimo that he had no such intentions. Secretly, he and his staff prepared evacuation plans to Chengtu and Kunming, the latter of which he viewed as an irreplaceable supply node whose military value far exceeded the threadbare Nationalist capital.

(Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In 1943 Chiang had agreed to send his best troops to fight with Stilwell in northern Burma as part of the American general’s attempt to open a supply line from India, through northern Burma, and into China. During the spring and early summer of 1944, at the dawn of Ichi-go, Chiang understandably chafed at having those troops in Burma while the Japanese threatened to overrun his country. Once again in the late fall he pushed for their return to defend Chinese soil. A supplicating Wedemeyer managed to persuade his old boss Mountbatten to agree to airlift two divisions, the 14th and the 22nd, back to China throughout December. American transport planes managed to move 25,105 soldiers and 1,596 horses and mules, plus weapons and equipment, into western China. Fortunately, the crisis passed, more due to Japanese limitations than the intervention of these divisions. Had the Allies understood more about enemy intentions, they might not have even gone to the trouble of airlifting these troops home. As always seemed to be the case in China, the Japanese could take territory, inflict tactical defeats on Nationalist forces, and unleash untold horrors upon the population. But they seldom possessed the manpower and logistical heft to establish real control over large swaths of territory, especially the farther inland they advanced from their coastal bases. They had no intention, nor really the capability, of pushing for Kunming and Chungking, both of which remained firmly under Allied control.

Promoted to lieutenant general on January 1, 1945, Wedemeyer focused on reforming the Chinese Army, just as Stilwell had before him. “Sometimes I feel like I am living in a world of fantasy, a never never land, but we are going to continue our efforts…despite discouraging experiences along the way,” Wedemeyer confided in a private letter to Hull. For all of Wedemeyer’s famous tact, he laid out the army’s many deficiencies for Chiang in frank terms, especially in relation to the paucity of food for the soldiers and the tyrannical nature of the draft system in which men were forcibly taken into custody, sometimes bound and tied like prisoners. “Conscription comes to the Chinese peasant like famine or flood, only more regularly—every year twice—and claims its victims,” he wrote to Chiang in a detailed memo urging immediate reform. “Famine, flood and drought compare with conscription like chicken-pox with plague.” While poor and illiterate people were brutally forced into service, the educated and the wealthy could evade the draft by hiring a substitute or paying an official. “One can readily see that it was the poor, weak, and those with insufficient money who were forced to defend their more fortunate countrymen against the Japanese invader,” one of Wedemeyer’s staff reports bemoaned.

To improve the treatment, care, training, and effectiveness of the average soldier, and thus the army as a whole, Wedemeyer urged sweeping reforms and reorganization. He proposed the creation of a new fighting force, known as Alpha, comprising between 36 and 39 divisions of 10,000 soldiers apiece, plus supporting troops. They were to be entirely trained, equipped, armed, and advised by the Americans. The plan bore an almost uncanny resemblance to one that Stilwell had proposed, in vain, to the Generalissimo a year and a half earlier. The only major difference was that Stilwell envisioned a 60-division force. Thanks to the Ichi-go scare, and perhaps owing to Wedemeyer’s more nimble diplomacy, Chiang agreed this time. The core of Wedemeyer’s strategy centered around launching an offensive with the Alpha Force in the latter half of 1945 designed to advance to the coast to reclaim the port cities of Hong Kong and Canton. This would achieve the dual objective of opening up another supply route for China and providing staging bases for the invasion of Japan. He spent most of his 1945 time and energy preparing to fulfill this objective.

(Corbis via Getty Images)

Chiang’s newfound tractability might well have owed just as much to his looming showdown with the communists as to any other factor. The Generalissimo continued to walk a perilous tightrope. The difficulties of holding together his own government, dependent as it partially was on alliances with corrupt, exploitive local leaders, while also pursuing reforms that inevitably diminished their power, would have challenged the acumen of even the most skilled political practitioner. Nor could Chiang afford to alienate the Americans on whom he depended for crucial Lend-Lease economic and military aid, not to mention the international prestige he received from their political support. For nearly four years, they had helped him stave off the Japanese; in turn he had played a crucial role for the Americans by absorbing, at terrible human cost, substantial Japanese manpower and resources.

As the power of the enemy now receded, and serious conflict with the communists bubbled, Chiang could not afford any deterioration in relations with the Americans, though they continued to prod him to consummate some sort of power sharing agreement with Mao. But Mao had no intention of submitting his troops to Nationalist authority, and Chiang knew that recognizing the political legitimacy of the communists could prove mortal to his own government. Mao and his Chinese Communist Party (CCP) envisioned no real endgame that did not include the triumph of their revolution, inevitably at Chiang’s expense. Chiang well understood, perhaps better than did his allies, that any attempt to share power with such zealots was like trying to divvy up freshly killed meat with a hungry lion—by its nature it tended toward a zero-sum game. Wedemeyer could make all the plans he wanted to hasten the demise of the Japanese in China. But, with each passing day, this mattered less compared to the burgeoning brawl that loomed between the Nationalists and the CCP, a conflict of world historical importance. In truth, neither Wedemeyer nor any other American truly had the power to prevent this civil war, one that ironically grew likelier and nearer as the war’s end finally came into view.

[ad_2]

Source link