[ad_1]

When a left-wing newspaper and a conservative newspaper both agree that the principles of neoliberalism are no longer working, things must really be going in the wrong direction – and this what happened in spring 2023, when the Federal Ministry for Education and Research in Germany presented its proposal for an amending law to the Act on Fixed-Term Employment Contracts in Academia.

Alex Struwe, in the left-wing Neues Deutschland, wrote about the ‘austerity system’ of the German university, which, under the pretence of innovation and competitive excellence, has created a systemic precarity built on the exploitation of labour, fuelled by researchers’ readiness to ‘self-exploitation’.

Surprisingly, Hannah Bethke, writing for the more conservative-leaning Die Welt, conceded that the German university wasn’t managing to live up to even the most basic standards of meritocracy: the Act on Fixed-Term Employment Contracts was failing researchers because – no matter their merits and contributions to research, teaching and admin – they would all inevitably run up against the limit of the fixed- term employment restrictions. This effectively banned researchers from further employment in academia unless they managed to land one of the absurdly rare permanent posts as senior lecturers or full professors.

In other words, Bethke was arguing that the government’s currently proposed academic employment policies – which are in the hands of the Free Democrat politicians running the ministry – are failing within the terms of their very own neoliberal meritocratic principles. Left- wing critics and proponents of neoliberalism seem to concur in their analysis of academic employment practices. How could it come to this?

A draft proposal for the legislation earlier in the year had already caused an uproar within the academic community, since it threatened to make the employment situation of junior researchers even more difficult than it already is. Rather unusually for obscure political debates on the university sector, the negative response from the academic community was quite fierce, leading to public protests in front of ministerial buildings in Berlin, and to prime-time coverage on public television.

The response was, however, the logical culmination of years of growing discontent, especially among early-career researchers and teaching staff at PhD and postdoc levels. The sustained response to the amending law in 2023 was made possible largely thanks to an academic protest movement that had formed during the first Covid-related lockdown periods in 2020 and early 2021, largely on Twitter. During this period a video was released by the federal education ministry featuring a young researcher – the complacently smiling Hanna – whose progress, condensed into a short instructional video, was supposed to illustrate the career paths of early- career researchers. However early-career researchers unanimously took offence at the video’s condescending and patronizing tone.

The video tries to expound the purpose and benefits of the existing Act on Fixed-Term Employment Contracts, a law introduced in the early 2000s that seeks – among other things – to help prevent exploitative employment structures in education by setting maximum periods for the PhD and postdoc phases during which fixed-term contracts are possible. The intention behind the act may have been noble, but over the almost two decades since it was passed it has been clearly demonstrated that it is in fact making things worse. The Act rules that early-career researchers must finish their PhD and their postdoc qualification after a period of six years for each of the two phases it involves (with possible extensions for child care or disability).

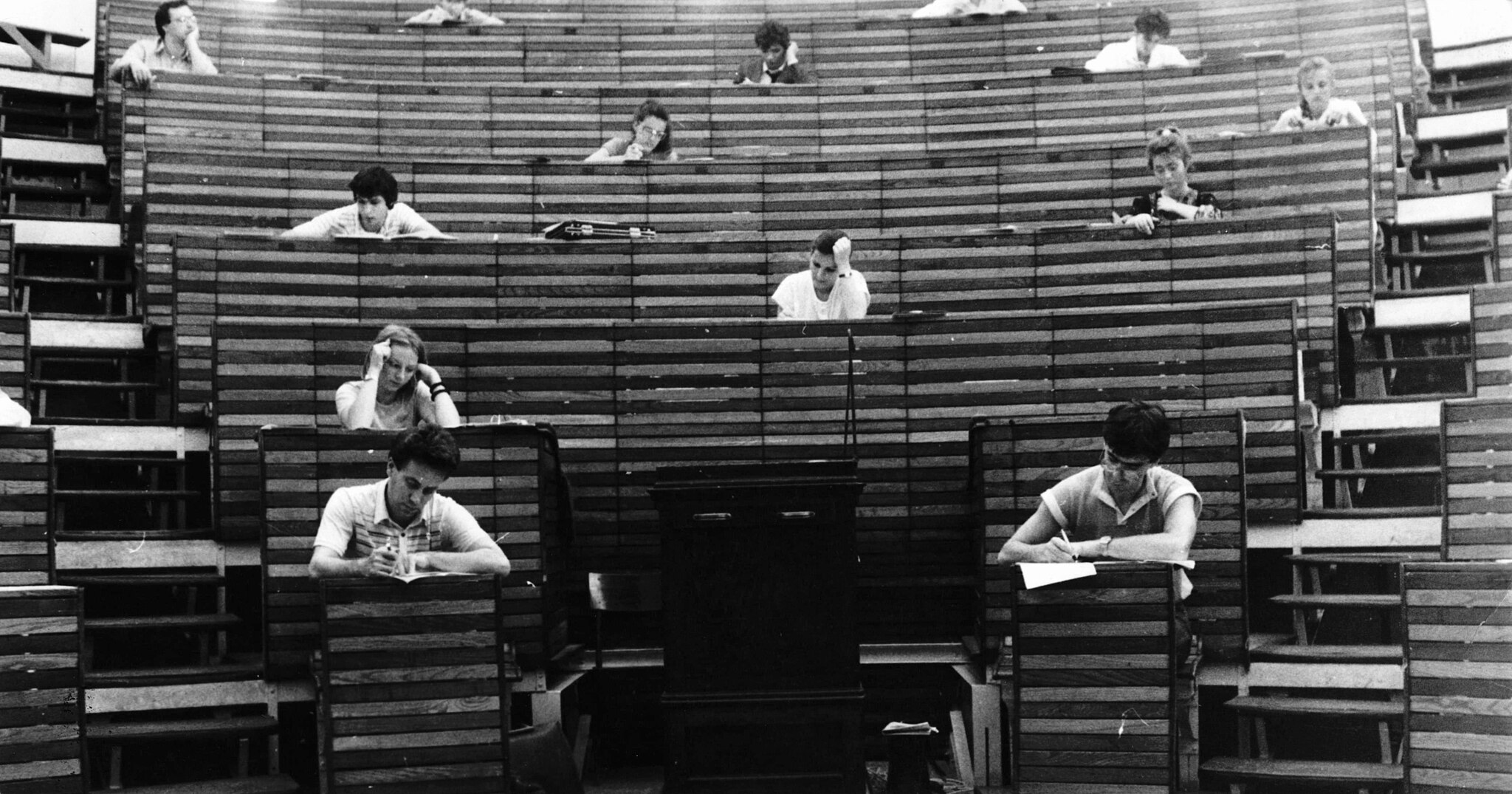

Image via Fortepan/Wikimedia Commons.

Academic precarity

After this twelve-year period, the assumption is that researchers will have been successful in being appointed to a regular professorship. Since professorships are incredibly rare in Germany, and are one of the few available forms of permanent employment for academics, the probability of success in such a pathway is quite limited. And – since permanent contracts for lectureships or other alternative research and teaching posts beyond a regular professorship are even rarer – it makes academic careers hard to plan, and puts a majority of young researchers into a position of virtual precarity (most of whom will be in their late 30s or early 40s when – and if – they complete their habilitation).

I use the term ‘precarious’ carefully here, since being in regular employment at a German university – even on a fixed-term contract – still comes with a range of benefits and privileges that many colleagues abroad do not enjoy, and which are also nowhere near the precarity of other job sectors. However, it is a particular form of academic precarity, and it is exacerbated by universities’ increased reliance on poorly-paid non-tenured teaching contracts without social security benefits. Especially in the humanities, these untenured jobs carry substantial teaching loads, which ideally should be carried by regular tenured staff.

In director Christopher Nolan’s recent blockbuster Oppenheimer, the eponymous physicist angers his superiors by encouraging his PhD candidates to join union meetings – ‘academics have rights too’, he explains, when he is asked what a scientist could possibly have in common with working-class strikers. This scene, taking place in the 1930s, still rings true in Germany in the 2020s – because, for far too long, German academics haven’t really taken the opportunity to organize in the designated trade unions for education and research workers. Not surprisingly, then, these unions have for quite some time been dominated by the concerns, issues and aims of schoolteachers and kindergarten educators.

This dominance is perhaps also a result of workers in this part of the education sector enjoying working conditions unrestricted by awkward and monstrously phrased acts regulating fixed-term contracts, which allow them the time and foresight to plan ahead. Scraping by on a fixed-term contract which expires within ten months, while still having to write that paper you promised your colleague, complete that habilitation to ensure your future employability, and write that third-party funding bid, all the while managing your teaching load and supervising MA theses – all this makes for a work model that isn’t particularly suitable for political engagement in trade unions.

Democratic participation

To ensure that democratic participation is possible for all academic staff, a democratic university requires solid employment schemes. Legally sanctioned restrictions on contract schemes undermine the basic preconditions for sustainable industrial action – one of the major pillars of democratization. Similarly, the pressures and demands of streamlining your CV in the shortest amount of time make it difficult to pursue detours, whether in research, teaching or political commitments.

During the lockdown years, however, fuelled by the increased demands made on academic teaching staff from remote teaching, and the lack of opportunities for assembling and discussing urgent issues, a new academic protest movement formed, on Twitter. It gained traction as a result of the intense strains of having to continue an uncertain career in even more uncertain pandemic times; balancing care for one’s family as well as for one’s remote students; and trying to keep one’s academic career afloat.

This social media activism helped revitalize trade union work in higher education. Online events during lockdown and subsequent in- person meetings of the German trade union for education and research (GEW) reflected a newfound awareness of the vital importance of unionizing for the democratization of the sector. It was this largely lockdown-bred new movement that immediately responded when the government announced their plan for an amending law. The movement had exposed the dire need for a resurgence of a democratic impetus within German academia.

While the debates around employment law may seem primarily to be about labour, it is also clear that they have wider repercussions for what a democratic university might mean and entail. A system of labour that leaves more than 90 per cent of employees in teaching and research on fixed-term contracts, in precarious positions and thus in quasi-feudal relations of dependency inevitably offers opportunities for abuse. So it did not come as a surprise when the protests also encouraged academics and students to come forward with their stories about toxic work environments and abusive supervisors.

The pressures of a system that is built on fixed-term PhD- and postdoc qualifications tend to breed new forms of intellectual conformity: research and teaching becomes more and more risk-averse. If the main goal is to field as many strategic publications as possible within a short span of time, there’s no time to take risks in thinking, writing, the lab or the classroom – and few risks seem worth taking for the sake of open debate.

This argument about constraints on non-conformity in universities is being developed, in a different way, by the political right. Emerging in 2021, at about the same time as the protest movement against academic precarity, the Network for Academic Freedom (Netzwerk Wissenschaftsfreiheit) went public with a ‘manifesto’, which declared the group’s aim ‘to defend the freedom of research and teaching against ideologically motivated restrictions and to contribute to strengthening a liberal academic climate’. For an English-language overview of the German situation and protests, see Amrei Bahr et al,

While this may sound laudable, it quickly became clear that what many of the members of this committee had in mind was a general concern with all things ‘woke’, accusing strands within the humanities, and cultural studies in particular, of being guided in their research and teaching by ideological dogma. As can be seen on the Network’s blog, the ensuing debates about the group’s concerns were in large part focused on debates about ‘cancel culture’ and ‘wokeness.’ Very often, it was the familiar narrative of the new right, blaming antiracism, gender studies, feminism and queer theory for allegedly shaping a political and intellectual hegemony in the university.

I don’t intend here to go into a detailed discussion of the various debates between the Network and its critics, or about the legitimacy or otherwise of their concerns about a ‘culture war’. What’s more interesting is to consider the Network (and the critical responses to it) as a symptom of wider concerns about the democratization of the university during the current cultural and political moment. During this moment, both sides of the debate about the threat to academic freedom – whether from the political left or right, whether unfounded or not – seem to echo what Jacques Derrida formulated more than two decades ago as the ideal of the ‘unconditional university’.

Crucially, for Derrida, this type of university did not yet exist. He hoped and proposed, however, that the humanities in particular would be able to contribute to its creation – the creation of the university as a sphere that is ‘more than critical’, reserving for itself the ‘right to deconstruction’: ‘Such an unconditional resistance could oppose the university to a great number of powers: to State powers … to economic powers … to the powers of the media, ideological, religious and cultural powers, and so forth – in short, to all the powers that limit democracy to come’. It is important to note Derrida’s emphasis on the unconditional university and its radical mode of (deconstructive) critique as something ‘to come’, to be lived and practised in anticipation. It is a becoming rather than something that will ever fully be. This is rooted in Derrida’s belief in truth-seeking as the core mission of the university, and of what he considers to be the ‘new’, ‘transformative’ humanities that will reinstate the university as a place of critique . These proposals resonate with current debates about the future of the university, and the idea of a democratic university.

However, Derrida’s speculation about the unconditional university to come has no answers to the inevitable economic questions – despite all its talk about the university as a concrete place challenging the then-emerging ‘cyberspace’ (an argument, however, which gain new importance in the context of a post- lockdown educational world.) No matter how emphatically and deconstructively one opposes economic powers, even an ‘unconditional’ university is inevitably conditioned by economic parameters. After all, neither scholars nor students can live on critique alone, and even deconstructivists must be fairly employed and paid. Thus, any debate about the democratization of the university must also recognise academic institutions as places of employment, and thus of labour rights and working conditions.

Source link