[ad_1]

People in Israel, Gaza and the West Bank are reeling from the repercussions of the 7 October attacks on Israel by the militant organization Hamas. Hamas members killed around 1,200 people, including at least 28 children, according to data being compiled by the newspaper Haaretz. Some 240 have been taken captive, including at least 33 children.

As of 15 November, the death toll from Israel’s bombardment of Gaza and subsequent ground operation is more than 11,000, including more than 4,500 children, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the UN children’s agency UNICEF. More than 1.6 million people have been made homeless, and 22 of Gaza’s 36 hospitals are not functioning, says the World Health Organization.

Researchers, science and health infrastructure are all affected. In Israel and the West Bank, laboratories are empty and most academic work has stopped or slowed. Many Israeli researchers have been called up as military reservists.

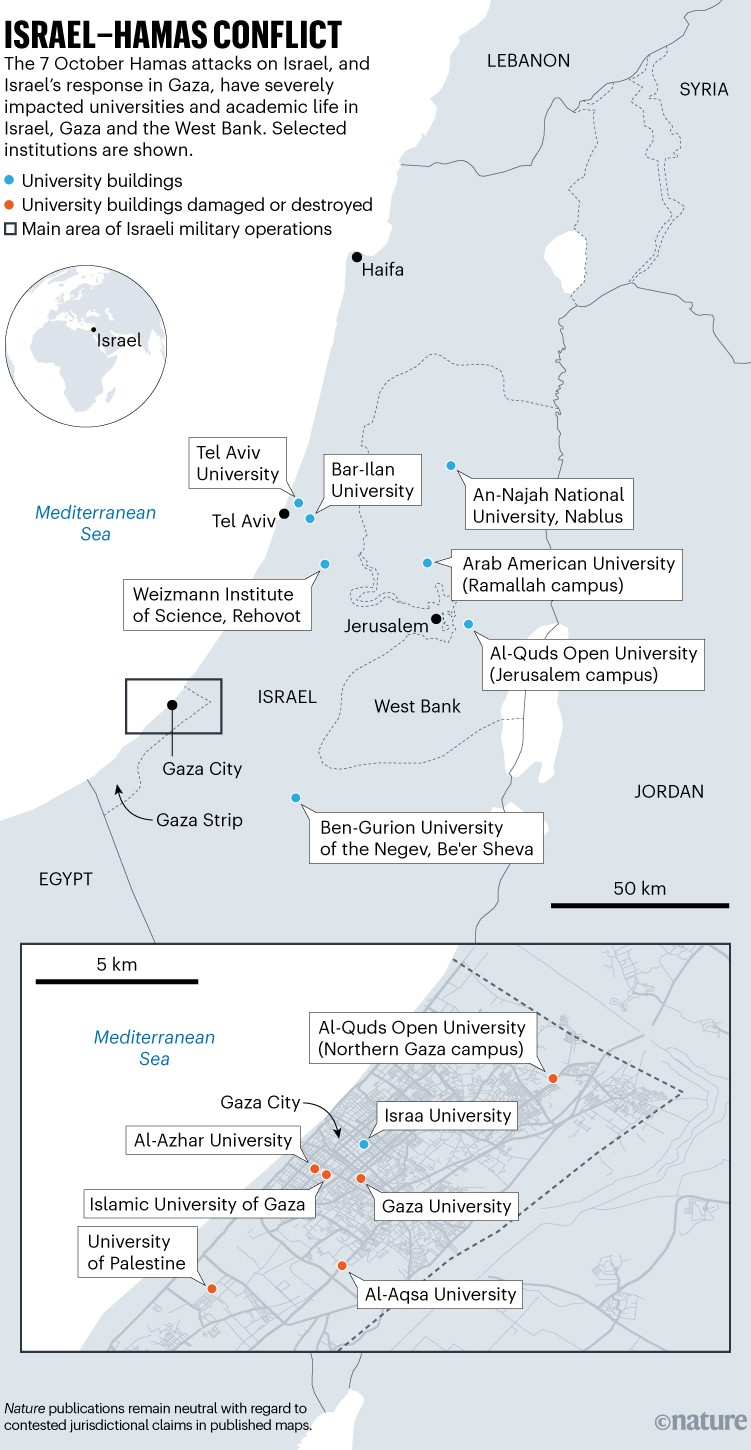

The United Nations Satellite Centre (UNOSAT) has told Nature that buildings at five out of Gaza’s six main universities have damaged.

Nature has spoken to researchers in Israel, Gaza and the West Bank, and to their international collaborators, to get their perspective.

Israel counts the cost

The fallout from the Hamas attacks on 7 October was felt by the academic community all over Israel, but especially in the south, near the border with Gaza, where the militant organization’s attacks took place.

One institution, Ben-Gurion University (BGU) of the Negev in the southern city of Be’er Sheva, around 40 kilometres from Gaza, lost 84 people, including students, faculty members and their relatives. A further five were kidnapped and nine have been injured, according to a university spokesperson. The dead include entire families annihilated in one day.

Among them was theoretical physicist Sergey Gredeskul, originally from Ukraine, and his wife Viktoria, killed in their home in Ofakim, about 20 kilometres west of Be’er Sheva. “Apart from being a great physicist, Sergey was also a musician, a storyteller and a historian of the famed Kharkiv school of physics,” says BGU’s head of physics, Oleg Krichevsky, who was a close friend of the family.

“On that day, we were contacted by Gredeskul’s grandson, who lives in Europe, and their daughter in Ukraine. He said that his grandparents do not answer the phone. So, we started to call them as well. After several unsuccessful attempts, I filed a missing person’s report with the police.”

After Krichevsky learnt that the couple had been killed, he went to their house to collect their belongings at their daughter’s request. He describes seeing bullet holes everywhere.

Sergey Gredeskul: “A great physicist, musician, storyteller and historian of the Kharkiv School of Physics.”Credit: Courtesy of the Gredeskul family, through the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

At Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan, near Tel Aviv, 34 students and relatives of faculty members were killed in communities in the south, or were among the at least 260 people killed when Hamas militants attacked the Supernova music festival near the border with Gaza. Three relatives of faculty members and students are among the roughly 240 people abducted by Hamas. The dead also include army reservists who tried to protect people from the attackers.

The Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, south of Tel Aviv, has also lost faculty members. One, Marcel Frailich Kaplun of the Department of Science Teaching, was murdered at Kibbutz Be’eri, the communal settlement where she lived. Her husband, Dror Kaplun, is still missing.

Frailich Kaplun was a researcher in the practice of improving science teaching, especially chemistry. “Marcel was the sort of person everyone loves working with – smart, dedicated, the kind who energizes others,” her colleague Miri Kesner wrote in a tribute published by the Weizmann Institute. She was “passionate about demonstrating chemistry’s relevance to industry and to our day-to-day lives,” Kesner wrote.

Marcel Frailich Kaplun: “The sort of person everyone loves working with — smart, dedicated, the kind who energizes others.”Credit: Courtesy of the Kaplun family, through the Weizmann Institute of Science

Arie Zaban, president of Bar-Ilan University, says the campus is empty, because the start of the academic year has been postponed and many PhD students and younger researchers have been drafted into the military. The university has opened a helpline for emotional support. The department of optometry has activated its Mobile Vision Clinic, which is travelling around to treat people evacuated from kibbutzim and cities in the south such as Ofakim and Netivot. “Many of the people, when they were evacuated, they lost their glasses, so [the optometrists] come in and do the eye tests, and they prepare special glasses for them,” Zaban says.

With tensions running high, Tel Aviv University is also supporting its Arab-Israeli students, who constitute 15% of the student population. “We have made it a priority to ensure these students feel safe coming to the University,” vice-president Millet Shamir said in a statement on the university’s website. “We instated a zero-tolerance policy toward incitement and hate speech on our campus, regardless of whether these are directed at Jews or Arabs.”

Gaza’s universities targeted

Israel’s bombardment and ground operation against Hamas in Gaza is taking its toll on universities and scientific infrastructure.

Gaza has 17 higher-education institutions, of which 6 are traditional universities, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, based in Ramallah in the West Bank. A seventh, Al-Quds Open University (AQOU), provides distance-learning education. All seven universities have campuses in areas that Israel’s military has ordered people to evacuate.

According to data from the Palestinian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, based in Ramallah, buildings in five of the traditional universities have been moderately or severely damaged, including Al-Azhar University — Gaza, Gaza University and the Islamic University of Gaza (IUG), all in Gaza City (see ‘Israel–Hamas conflict’). UNOSAT has independently found damage to buildings at the same five universities. An imagery analyst from UNOSAT told Nature that the agency uses “visual change detection analysis”, a method of comparing satellite images collected before and after an event to locate and assess damaged buildings.

Source: Ministry of Scientific Research and Higher Education in Ramallah/UNOSAT

Nine out of the 14 buildings at the IUG, the oldest degree-awarding institution in the territory, were destroyed in two waves of bombing on 9 and 11 October, including science labs, information-technology buildings and medical-education buildings. None of the IUG’s 17,000 students or more than 300 faculty members were on site at the time of the destruction. However, many have been killed or injured in other bombings, says Amani Al Mqadma, the university’s head of international relations.

In an 11 October press statement and accompanying video, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), the country’s military, confirmed that it had attacked the IUG. According to the statement, the university was being used as “a training camp for military intelligence operatives, as well as for the development and production of weapons” and conferences were being used to “raise funds for terrorism”.

Nature asked the IDF whether it could provide evidence that the university was involved in unlawful activity. An IDF spokesperson replied in a statement sent by e-mail: “The IDF is currently focused on eliminating the [threat] from the terrorist organization Hamas. Questions of your kind will be looked into in a later stage.”

Nine out of 14 buildings at the Islamic University of Gaza, the oldest degree-awarding institution in the territory, have been destroyed.Credits: Ashraf Amra/APA Images/ZUMA Wire/Alamy, Hassan Eslaih/Islamic University of Gaza

Nature was able to reach four researchers at universities in Gaza. Three of the four have been made homeless since the start of the bombing and are among the more than 1.6 million people who have been internally displaced in response to IDF instructions to move south. All expressed a feeling that they are now alone.

AQOU’s Gaza branch has also reported damage from bombings. Mohammad Abu Jazar, an environmental engineer at the university, says he has lost all hope that the international community will come to their aid. “I apologize for my boldness, [but I] don’t believe there is a scientific community, or global scientific community, that can do anything.”

Hatem Ali Elaydi, an electrical engineer at the IUG, says he is hosting 74 people from 7 families in his home. He says a daily priority is to look for food, clean water, medicine, cleaning supplies and clothes for families who have lost their homes. “There is no electricity, no Internet, no drinking water, no fuel” and the families are drinking salty water from the sea. He says they start their day by checking on each other to see who they have lost in the previous night’s bombing.

Bill Williamson, a social scientist at Durham University, UK, has been conducting research for a forthcoming study on Palestinian higher education. “I was writing about a system, with all its flaws, that was still working. It is now, at least in Gaza, being destroyed,” he says.

West Bank fears

Parts of local government in the West Bank, which is home to almost three million Palestinians, are run by the Palestinian National Authority. However, Israel retains responsibility for borders and security, and its citizens have been settling in the area in growing numbers.

According to the OCHA, as of 15 November, 183 Palestinians have been killed by Israel’s security forces in the West Bank since 7 October, bringing the death toll for 2023 to 427. Three Israelis have been killed in attacks by Palestinians, the UN says. On 9 October, Israel’s Firearms Licensing Department launched what it called “an emergency operation to enable as many civilians as possible to arm themselves”.

Researchers to whom Nature spoke say that this increased violence has stopped in-person teaching and research at the West Bank’s 34 higher-education institutions, which include 13 universities — worsening existing difficulties for staff and students.

Majdi Owda, a data scientist at the Arab American University in Ramallah, says students and faculty members are now at increased risk of being shot if they travel to campuses. This is partly also because Palestinian motor vehicles can be identified by their number plates. “At the moment, we cannot allow anyone to travel in such an environment,” he says.

“Safety comes first,” adds Raed Debiy, a spokesperson for An-Najah National University in Nablus in the West Bank. Debiy says the university is sending medical students who have completed their clinical training to hospitals across the West Bank to help people who have been injured.

Imad Barghouthi: “His early works on the dynamics of plasma in the cosmological context have had international relevance.”Credit: Courtesy of the Barghouthi family

Arrests of Palestinian academics and students have also been stepped up. For many years, Israel’s authorities have used administrative detention orders — a legal procedure that allows the military to arrest and imprison people considered a security risk, without needing to explain the charges against them. At the end of June this year, 1,117 Palestinians were in detention under this system, according to the human-rights watchdog B’Tselem in Jerusalem. More recent data are not yet available.

On 1 November, astrophysicist Imad Barghouthi of Al-Quds University in Jerusalem was sentenced to prison for six months after police broke into his home at 3 a.m. on 23 October, handcuffed him and took him away, according to his daughter Duha.

Mario Martone, a theoretical physicist at King’s College London and a member of Scientists for Palestine, which promotes research in the Palestinian territories, is campaigning for Barghouti’s release. He says Barghouthi is influential in his field. “His early works on the dynamics of plasma in the cosmological context have had international relevance. He has no political affiliation and has never carried out violent actions,” says Martone.

Nature contacted the IDF for further details about Barghouthi’s arrest. It referred us to the Israel Security Agency Shin Bet and the police. Neither had responded by the time this article was published.

Hopes for collaboration

Universities in Israel, Gaza and the West Bank work extensively with institutions overseas, but there is little in the way of cooperation between Israeli and Palestinian institutions.

For now, many international collaborations are on ice. Some researchers hope that this will be temporary, and that the international community will get behind rekindling collaborations, along with rebuilding Gaza’s education and research infrastructure once the current conflict finds some form of resolution. But others are much less confident.

Hicham El Habti, president of Mohammed VI Polytechnic University (UM6P) in Salé, Morocco, was among the first to reach out to Daniel Chamovitz, president of BGU, to express sadness and solidarity after the 7 October attacks. For two years, the universities have been cooperating on projects relating to sustainability and climate change under the 2020 Abraham Accords, in which Israel and some of the neighbouring Arab countries began normalizing relations. Delegations of students and faculty members have travelled back and forth between BGU and UM6P, initiating research programmes on agriculture, water, energy and land restoration.

Chamovitz wants such collaborations to continue and even expand. He told Nature about the warm relationship between BGU and UM6P, as well as other Moroccan universities. “UM6P even has a synagogue on campus for visiting Jewish students,” Chamovitz says.

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in southern Israel conducts work with institutions in Morocco.Credit: Eddie Gerald/Alamy

The current situation “is really sad, really traumatic”, says Arie Zaban, president of Bar-Ilan University and chair of the Association of University Heads in Israel. “But at the same time, I know that we will overcome this, and we will make this a better place, in the name of the people who lost their lives.”

Bar-Ilan has a bilateral cooperation agreement with the Moroccan National Energy Transition Consortium, which includes 20 research groups from Moroccan universities. Zaban expects these collaborations to continue. “Those projects are typically at the level of person-to-person, and once it’s at the level of people speaking to people, it’s a very strong relationship and it takes a lot to break it,” he says.

At the same time, most international students and researchers who were working at the Weizmann Institute have returned, or are returning, to their home countries, says Weizmann Earth scientist Eyal Rotenberg. International scientific collaboration is being severely affected.

It’s a similar story in the West Bank. Debiy of An-Najah University says that joint projects, including conferences with colleagues from Europe and the United States, are being cancelled or postponed. International academics can no longer come to the West Bank, he says. “It’s not even safe to access the bridge between Jordan and Palestine anymore.”

“We had an international conference on dentistry that was postponed. An international research conference for medical students, which was supposed to begin on 8 October, has been completely cancelled,” he adds.

Some informal cooperation did exist between researchers from Israel and the Palestinian territories. But Yaakov Garb, a social and environmental scientist at BGU, says his Gaza-based colleagues now “spend most of their days looking for clean water and basic supplies”.

Williamson is a trustee of the Durham Palestine Educational Trust, a UK charity which supports Palestinian students and researchers to study at Durham University. He is holding out hope “that when this war ends, we can encourage governments and concerned academics to put their thinking caps on to help the reconstruction of Palestinian higher education”.

“It is not just a good thing for Palestinians; it is essential for the collective security of the Middle East and, frankly, a better world, that we do this.”

Source link