[ad_1]

From a ridge in the Samichon Valley known as the “Hook” Lance Cpl. Mike Mogridge watched as British artillery rained shells on an onslaught of Chinese infantry. Such was his introduction to the Korean War. The next morning, after the shelling had stopped and he and his mates had had breakfast, Mogridge and fellow soldiers clambered atop the Hook to gaze on the spectacle of pockmarked ground littered with the corpses and body parts of thousands of enemy troops. The British had held the line of resistance.

Tasked with collecting the British dead from no-man’s-land, Mogridge ventured out with his patrol under the cover of darkness with empty body bags. Sporadic gunfire from Chinese positions kept them alert. Manhandling the shell- and bullet-mangled bodies into the bags was difficult enough, and rigor mortis made it harder. Worse still, if the bodies had lingered in the valley too long, they were putrid with maggots. Seventy years after war’s end Mogridge still recalls the odor.

(Imperial War Museums)

Back at camp, after having carefully stacked the corpses, Mogridge and mates would settle into their ridgeline hutchie, a crude dugout ringed with sandbags. (The word “hutchie” derives from uchi, the Japanese word for house.) In their respective hutchies British soldiers ate, joked with mates, slept and otherwise pretended it was a peaceful retreat. Doing so helped them ignore the bodies stacked 8 feet high and consequent giant rats that infested the garrison.

“We got immune to it,” Mogridge recalls. “We just didn’t bother about it.”

Like so many other servicemen sent to Korea, Mogridge was drafted into the British army at age 18. British draftees typically traveled across the empire for a year, docking in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Singapore, Malaysia and Hong Kong before deploying to Korea. Finally, on reaching their 19th birthdays, they were deemed eligible for combat. “You weren’t allowed to be shot before you were 19,” one veteran joked.

Of course, turning 19 did not magically transform such boys into battle-hardened soldiers. Some, like Private Roy Painter, looked forever young—“about 12 years old,” by Painter’s own estimate. His commanding officer often remarked the private should have been back home with mother. But Painter notes his service, though he loathed it at the time, left a deep and strangely positive impression. “I contributed something,” he says. “My national service had some meaning behind it.”

Painter vaguely understood the war in Korea was proxy to a global Cold War between communism and democracy. Even so, he said, “Nobody seemed to know where Korea was.” Private Edgar Green of the Middlesex Regiment arrived in August 1950 with the first British land troops. They knew nothing of the country or its people. Major John Lane of the Royal Artillery reasoned such considerations were beyond his “periphery of interest.” He only worried about those things he could see. “You don’t get involved in…thinking if it’s right or wrong,” he recalls. “It’s just a small area around you that holds your interest, especially if somebody’s firing bullets at you.”

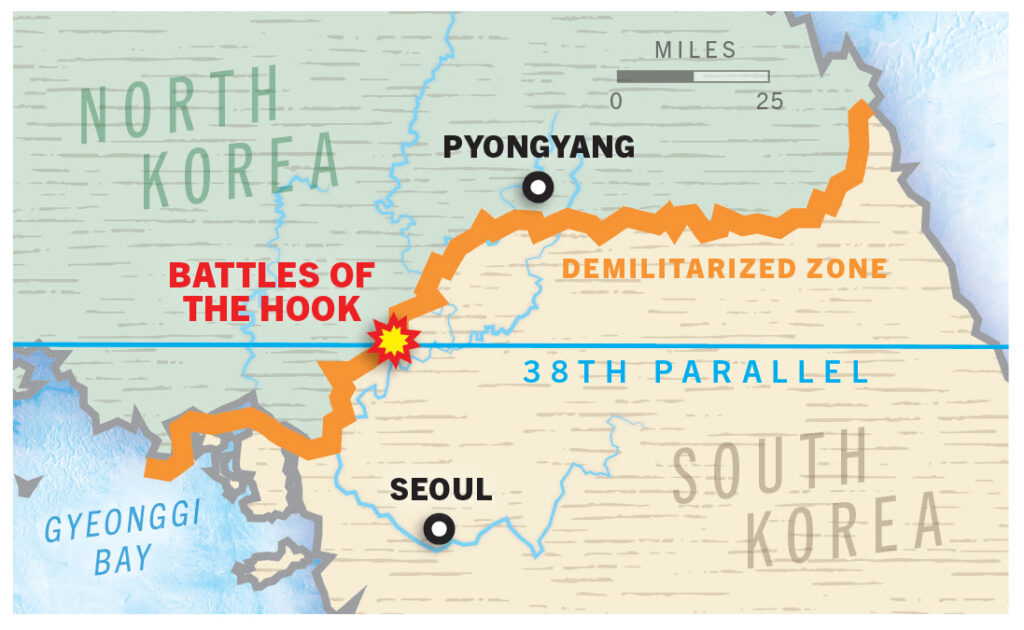

Like countless soldiers before them, Lane and Green expected to be home for Christmas. Within a month of their arrival United Nations forces launched a triumphant counteroffensive against the North Koreans. Led by iconic American General Douglas MacArthur, they defended a small perimeter around the southern port city of Pusan before breaking out and invading North Korea. The first British troops traveled the length of the peninsula. Green’s Middlesex Regiment protected Pusan in the south, took the port city of Inchon at the 38th parallel, then pushed past Pyongyang en route to the Chinese border. They walked when they could not hitch a ride on an American transport. It seemed they never stopped moving.

In October the People’s Volunteer Army of China joined the war, pouring south across the Yalu River to push U.N. forces south. Joining the retreat, the British withdrew beyond Seoul and the 38th parallel. Green marched south and then north again to retake Seoul. “We was here one day and then going forward the next,” he recalls. “Then, after we’d got right up as far as we could in North Korea, we started to come back, and that was the same.”

After a year of offensives and counteroffensives, the war settled into a status quo stalemate along the 38th parallel. There, the British struggled to maintain control of the south bank of the Imjin River, a natural border between the combatant armies. In April 1951 the Chinese attempted to cross the river to retake Seoul and Inchon. The defenders incurred heavy casualties, in particular the vastly outnumbered 1st Battalion of the British Gloucestershire Regiment, which made a strategic retreat to high ground to hold back the Chinese. The “Glorious Glosters” resisted wave after wave of attacks for four days, at one point ordering friendly artillery to fire on the hill they occupied to stave off a Chinese assault. When their ammunition ran low, the Glosters attempted a daring escape to reunite with the U.N. forces. The survivors of only one company made it. More than a third of the regiment perished, while nearly 1,200 were injured or taken prisoner.

(Imperial War Museums)

(Oktober64 (Getty Images))

As tragic as their stand was, it gave the British troops a reputation for unparalleled courage and dedication to the U.N. cause. But the Battle of the Imjin River was only the first heroic sacrifice the British would make on the front lines. The subsequent Battles of the Hook would propel the British army in Korea into the annals of military history.

The First Battle of the Hook began in early October 1952. Over the course of two weeks the Chinese army captured a dozen American and South Korean outposts along the front line. It left the 1st U.S. Marine Division to defend the Hook without much support along the 38th parallel. By month’s end the Chinese had gathered their forces for a direct attack on the Marines. Intense bombardment destroyed the defensive walls the Americans had built and even threatened to destroy the very ridge of earth around the Hook. The Chinese had gained the upper hand, and in a final push they sent a three-pronged infantry attack to surround the Marines, briefly overrunning and capturing the position. American air superiority reduced the effectiveness of the Chinese charge, and the Marines fought back, crawling from crater to crater around the ridge until the Chinese abandoned the Hook. As morning broke on October 28 the Americans counted nearly 80 dead Marines and more than 400 wounded. But the field was theirs.

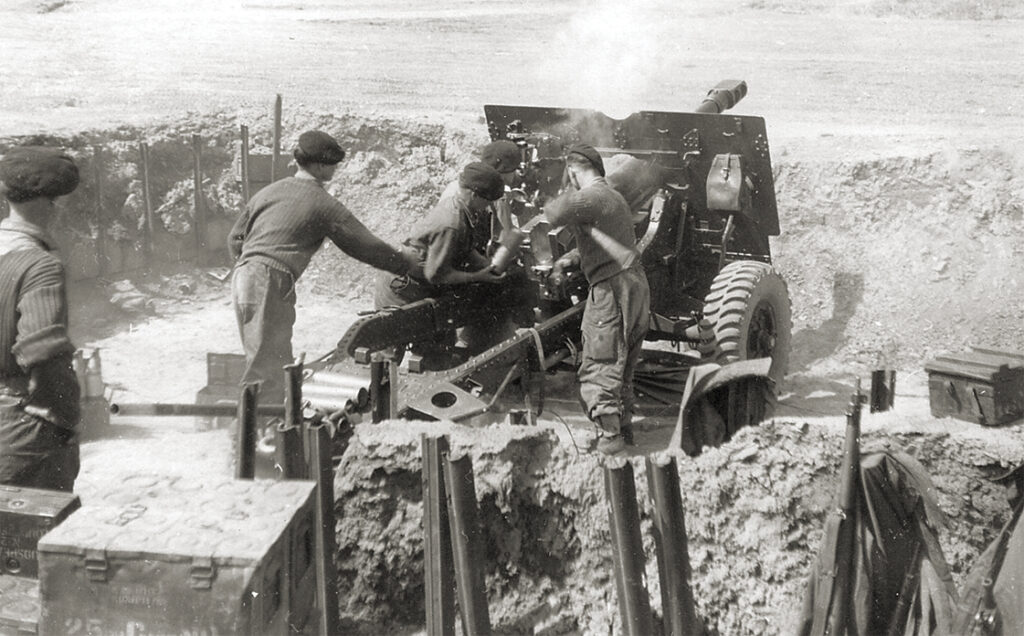

In dire need of rest, the Marines turned over the defense of the Hook to their allies in the British Commonwealth forces. The Scottish Black Watch and the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment took over. Three weeks later the Chinese attacked again. Fortunately for the British, they had readied reinforcements on the ridge. Their defense withstood the preliminary Chinese mortar and howitzer shelling. “We responded with what we called defensive fire,” one artillery gunner remembers, “prearranged and prerecorded to go on lines of approach to the Hook that the Chinese were liable to take.” Then the communists sent thousands of soldiers on a seemingly suicidal charge through no-man’s land.

Armed with PPSh-41 “burp guns,” submachine guns that made a brrrrip sound with each volley fired, the Chinese stormed across the battlefield on the night of November 18/19. The burp guns were effective weapons, but they were no match for artillery and rifle fire. The first wave of Chinese infantry was cut down long before it reached the barbed wire around the British trenches. The second line of Chinese infantry had rifles, and a third line carried grenades. When the first line of Chinese fell, the second and third lines picked up the burp guns and used them. They, too, had little chance against the well-fortified British, but the sheer volume of Chinese made the Hook a treacherous place. The fighting went on all night. The Chinese shot out searchlights, making it difficult for the British to spot targets, but artillery continued to rain indiscriminate death on the attackers. A rumor spread, Mogridge recalls, “that there had been more poundage [of bombs] dropped on the Hook that night than there had been during the [World War II] Battle of El Alamein.”

Dawn revealed the extent of the carnage. “We must have killed thousands,” recalls Major Lane, who wondered if the Chinese had given their soldiers drugs or whether they were simply that brave.

(Corbis (Getty Images))

(Keystone-France (Getty))

Skirmishes at the Hook became commonplace, but the Chinese did not stage another large-scale invasion to retake the position until late May 1953, weeks before the armistice would suspend hostilities. The Third Battle of the Hook was a Chinese attempt to strengthen their bargaining position in the peace talks by taking strategic locations on the front line. If they could capture the Hook, they might gain leverage in the forthcoming negotiations. Every inch of ground became important. The British had withstood all previous attacks on the Hook, and by the outset of the third battle they had dug in so completely that the Chinese had little chance.

Tactical Takeaways

Don’t count chickens. Given the initial success of Operation Chromite and the breakout north, British troops expected to be home by Christmas 1950, not ’53 or later.

Take the high ground. The vantage of the Hook gave its defenders ideal fields of fire into a key supply route and the likely path of invasion to Inchon and Seoul.

‘But did you die?’ A common refrain among soldiers facing myriad unpleasantries, that mindset wasn’t lost on British troops, who sought calm amid the chaos at the Hook.

The Duke of Wellington’s Regiment and the Royal Fusiliers were tasked with defending the ridge, allowing the Black Watch to move to the rear for some hard-earned rest. The 20th Field Regiment of the Royal Artillery would supply heavy firepower. When the main attack began on May 28, British gunners fired shells with proximity fuzes that exploded at variable intervals in midair, raining shrapnel on the Chinese soldiers and prompting them to dig sheltering caves and trenches into the reverse slopes of the Samichon Valley.

With the enemy scattered in dugouts around the Hook, the British could not repel them with artillery alone. A ground attack became necessary, and 2nd Lt. Brian Parritt, a gunnery officer, joined the British infantry and sappers on a night raid to destroy the caves. As darkness descended, the British mission ventured across the craggy valley. Almost as soon as his group reached open ground, it suffered casualties. A soldier walking beside Parritt stepped on a bounding landmine. When triggered, the explosive sprang into the air waist-high, killing Parritt’s companion, severing the leg of another soldier and knocking Parritt to the ground with minor shrapnel wounds.

Amid the bewildering din of gunfire and shelling, Parritt and the others converged on a large cave. Placing charges on long poles, the British sappers pushed the poles into the ground around the Chinese position. To cover their activities, Parritt called in artillery support. He had to be both quiet to avoid discovery and precise with the enemy location to avoid friendly fire. Wrapping up their work, the sappers pulled back with the others and detonated the charges. The blast threw up great mounds of dirt, and it quickly became apparent the assignment had succeeded. The cave had been destroyed.

When Parritt returned to the British trenches, he discovered the shrapnel from the bounding landmine had caught him in the leg, and he was sent to a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (M.A.S.H.). His time away from the front was made all the easier knowing the British had survived the Third Battle of Hook. Indeed, the British had proven they were a formidable adversary.

(Imperial War Museums)

Only when the British soldiers took leave and returned home did they begin to realize the part they had played in world history. Mogridge believes the war “stopped the march of communism” and speculates that had the U.N. not “confronted the North Koreans and the Chinese, virtually half the Far East would have been under communist Chinese rule.” Watching refugees flee the North Korean regime convinced Painter communism was incompatible with the rights and liberties for which he and his mates had fought. “When the North Koreans got to a village, they shot everybody,” Painter recalls in horror. “We’re talking about babies and toddlers. Can you imagine a couple of roads near where you live, and they kill everybody? It’s beyond our comprehension, isn’t it?”

Private Anthony White of the Royal Ulster Rifles notes that he and other veterans of the Korean War are “not appreciated” by the British public. Few citizens realize that nearly 100,000 British Commonwealth servicemen fought in the war, more than 1,000 of whom were killed. Americans call it the “Forgotten War,” sandwiched between World War II and the Vietnam War. The U.S. government finally commemorated its Korean War veterans with a memorial in Washington, D.C., dedicated in 1995, but the British government has yet to do the same. In 2014 a memorial was unveiled in London outside the Ministry of Defense, but the British government did not fund it. South Korean multinational corporations, the South Korean Embassy in London and South Korean expats paid for the sculpture. If Korea is the “Forgotten War,” the British veterans are its forgotten warriors.

(PictureLake (Getty))

One group has never forgotten the British sacrifice: South Koreans. The peninsula remains divided, as no treaty was ever signed, which means the war continues despite the armistice. And Koreans on either side of the 38th parallel still mourn the traumatic loss of upward of 2 million civilians. But today South Korea is a thriving republic, one that surviving British veterans, now in their late 80s or early 90s, justly celebrate. Private William Shutt, a signalman with the Royal Artillery who died in 2021, considered his wartime service among his greatest accomplishments (along with his three children and a happy marriage). The prosperity of South Korea since the 1950s left him in awe. To think he played some small part in helping the country on this path made him immensely proud. “They’ve made fantastic progress,” Shutt said. “When we first got to Korea, when the war first started, it was mainly rural. Rice paddies, that sort of thing.” Shutt returned to Korea in 2016 on a trip paid for by the South Korean government in honor of surviving veterans. What he found was a country transformed. “The great long stretch of the coastline is all factories.” Shutt noted that Koreans who have since immigrated to the United Kingdom often thank him when they learn he fought in the war. “If I went to a Korean restaurant, and I got a Korean meal, nine times out of 10 it’s a free meal. I couldn’t get that in a British restaurant. It’s one of these unexplainable things. We’ve got great respect for them; they’ve got respect for me.”

Today the Hook is smack in the midst of the demilitarized zone—the most heavily fortified border in the world. While so much has changed over the past 70 years, the Hook remains on the front line of the war.

Award-winning author Michael Patrick Cullinane is professor of history and the Lowman Walton Chair at North Dakota’s Dickinson State University. For further reading he recommends The Korean War: A History, by Bruce Cumings, and A Forgotten British War: The Accounts of Korean War Veterans, co-edited by Cullinane and Iain Johnston-White.

This story appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of Military History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.

[ad_2]

Source link