[ad_1]

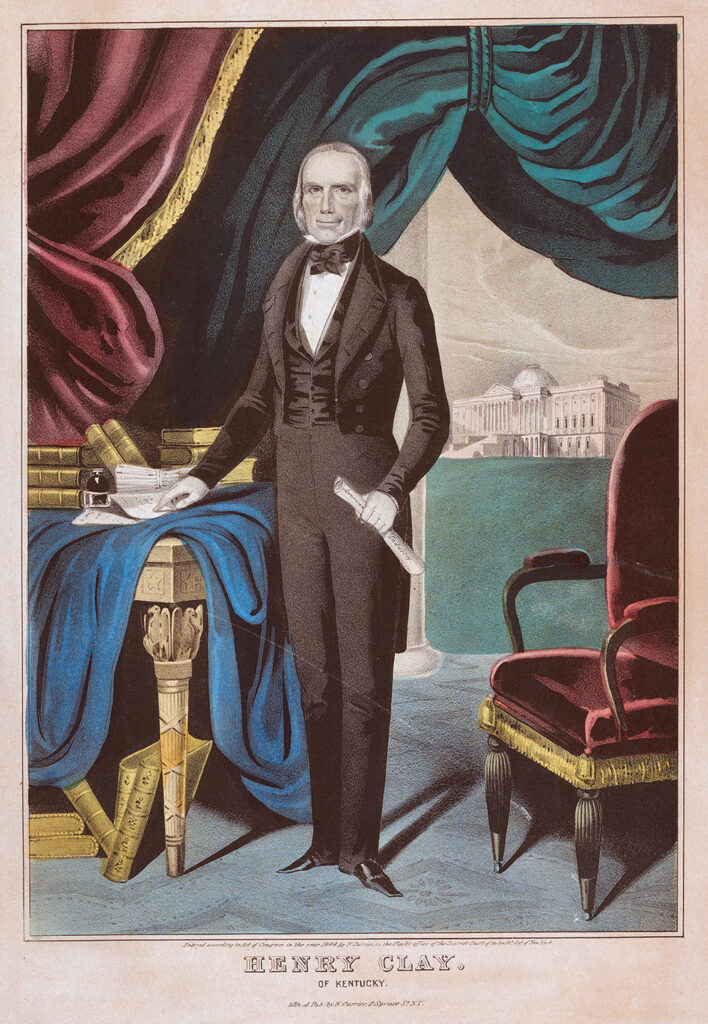

Henry Clay, nicknamed the Star of the West and the Great Compromiser, served as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives and a U.S. Senator from Kentucky, but he’s less known today than he was in his own time and for most of the 20th century. Time often takes a toll on the famous, even when they’ve accomplished great deeds, but Clay, a moderate politician during the turbulent antebellum decades before the Civil War, should stand as one of our perennial American heroes because his efforts in the national government consistently brought the country back from the brink of disaster. Today, when compromise seems to be a bad word in politics, Clay lets us remember that the give and take of politics is precisely what keeps a democracy alive.

He was born in Virginia in 1777, less than a year after the Declaration of Independence. As a young man, he read law in Richmond and clerked for the famous attorney and scholar, George Wythe of Williamsburg, before moving to Kentucky. Later in life, he claimed humble origins for himself, but his father (who died young) and his mother (who later remarried) firmly belonged to the frontier class known as the middling sort.

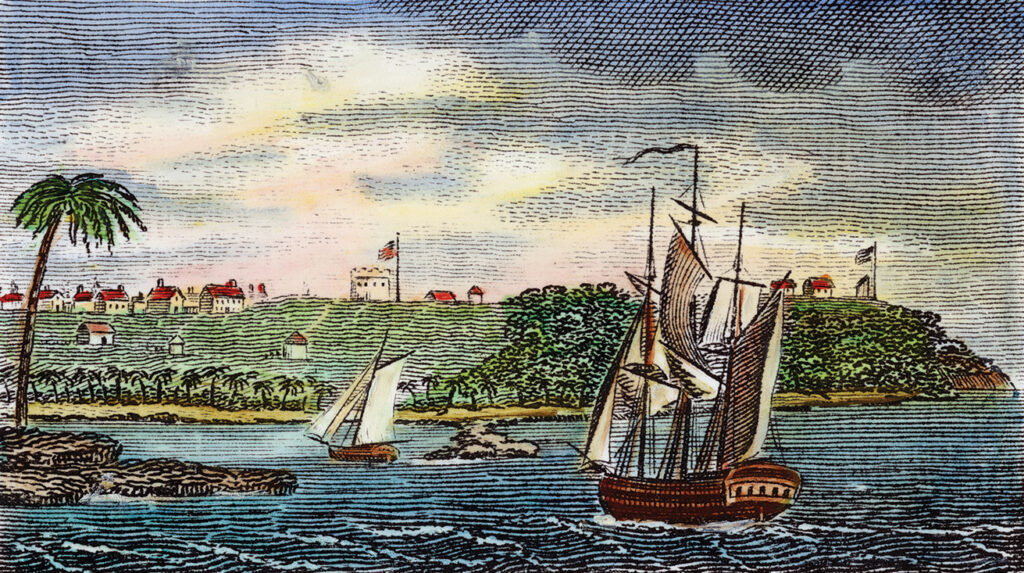

(Heritage Images (Getty Images))

In Kentucky, Clay practiced law with extraordinary skill and attracted clients who expanded his network of political contacts and social climbers among the elite of Lexington, the seat of Fayette County in the heart of the Bluegrass region. Soon he developed a reputation for hard work and hard play: he perfected his public speaking skills, modeling himself on Patrick Henry, wooed jurors to hand down verdicts in his clients’ favor, and relaxed by playing cards, gambling on horses, and drinking.

In 1799, he married Lucretia Hart, the daughter of one of Kentucky’s leading political figures. Marriage and the subsequent birth of 11 children did not slow him down—not in his work as an attorney nor as a carouser who enjoyed nothing more than a card game lasting into the wee hours of the morning and a glass of smooth Kentucky bourbon by his side. Friends and admirers called him “Prince Hal,” a reference to Shakespeare’s Henry V. When asked if she minded Clay’s gambling, Mrs. Clay replied coolly: “Oh! dear, no! He ’most always wins.” Meanwhile, while he wasn’t in card games or at the racetrack, he found comfort at his impressive house, Ashland, a sprawling, whitewashed brick mansion just outside of Lexington. Visitors approaching the stately house often heard wafting melodies sent aloft by Clay on his fiddle or Lucretia on her piano.

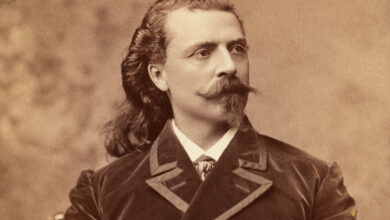

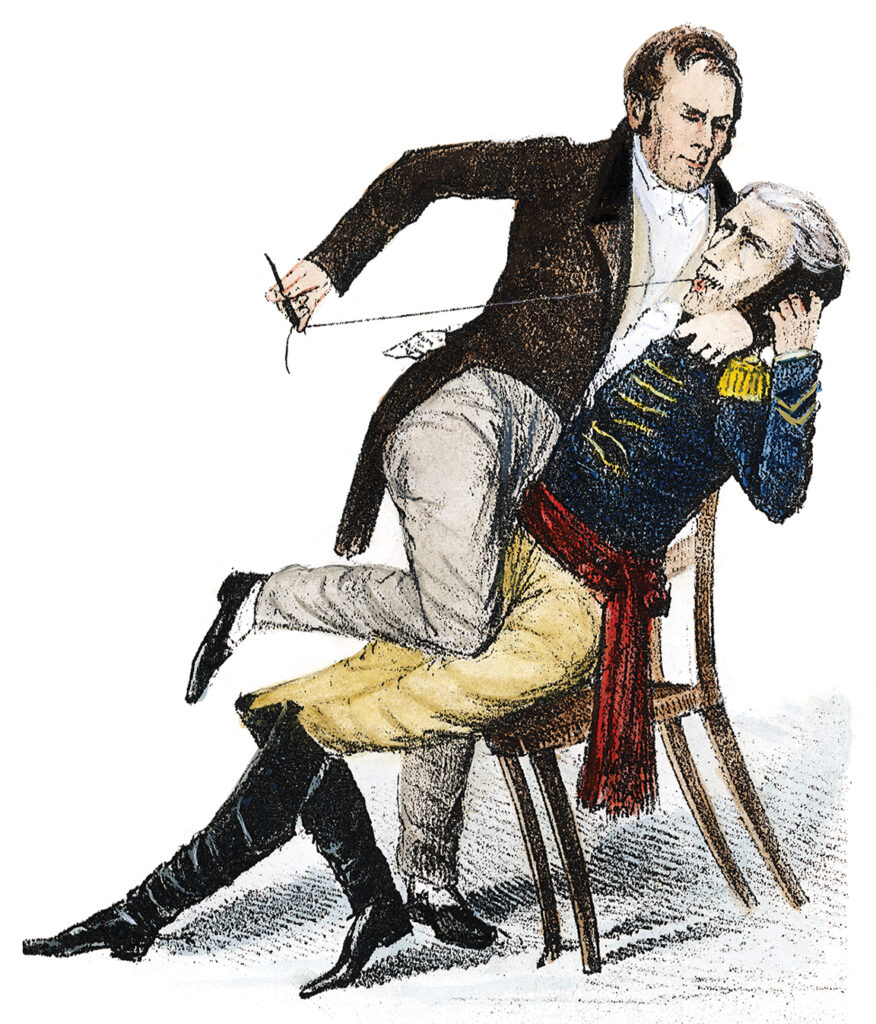

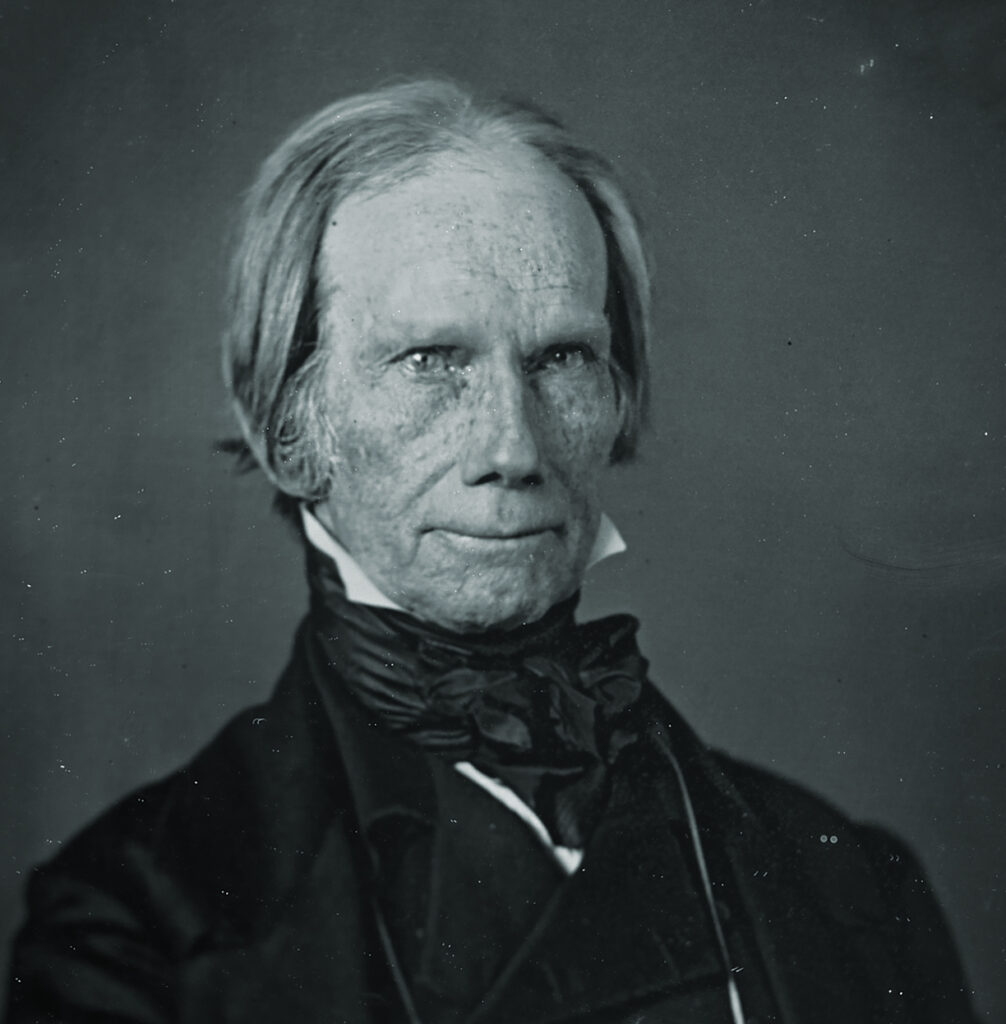

Tall and slender in stature, with wispy blond hair that revealed a high forehead, an angular face with round eyes, a long narrow nose, full lips, and protruding ears that kept him from ever being described as handsome, Clay rose quickly in state and national politics. After being elected to the lower house of the Kentucky legislature in 1803, he briefly filled a vacant seat in the U.S. Senate, successfully defended Aaron Burr against charges of conspiring to invade Spanish territory (only later did President Thomas Jefferson order Burr’s arrest for treason, but lack of evidence led to Burr’s acquittal), and became speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives. Although even tempered, his blood could sometimes run hot, and he, like other Westerners, protected his personal honor with a rigor that occasionally led him into folly. In 1807, for instance, he quarreled with a fellow legislator over Jefferson’s Embargo, and when his political opponent called him a liar, he challenged the man to a duel, a showdown that ended with both men wounding each other. It was not the only duel he fought over politics.

Starting out as a Jeffersonian Republican, he slowly drifted toward Hamiltonian domestic policies that looked to the federal government for support of economic development, a policy that would aid commerce in the West and tie the nation’s separate regions together. Clay took a moderate position on the issue of slavery (he argued for the gradual manumission of slaves and later became a founder of the American Colonization Society, a group of prominent national leaders who sought to free slaves and pay for their return to Africa) and maintained an unbridled belief that the West was the great stronghold of democracy. In 1810, he filled a vacant U.S. Senate seat once more and spent a great deal of time crying out against Great Britain’s impressment of American sailors on the high seas and its failure to comply with the stipulations of the peace treaty of 1783 that ended the Revolutionary War—in particular, British refusal to abandon their forts and outposts in the West.

(Library of Congress)

(Library of Congress)

Clay and others, who became known as War Hawks, worked diligently in Congress for a declaration of war against Great Britain. Always eloquent and authoritative, Clay’s rousing speeches prompted John Quincy Adams to remark that the Kentuckian was a “republican of the first fire.” Over his long political career, he would become known as “the greatest natural orator the world ever produced,” which, naturally was a gross exaggeration, but his effectiveness in delivering a speech was never in doubt.

Having become a household name, Clay won election to the U.S. House of Representatives, which he preferred to the “the solemn stillness of the Senate Chamber.” When he took his seat in November 1811, he was elected Speaker of the House, an achievement that revealed how politically astute he was and how popular he had become. But the War of 1812 went badly for the country, so much so that Washington, D.C., fell into enemy hands, and the British unceremoniously burned the city, leaving behind the charred stone shells of the Executive Mansion, the Capitol, and the Library of Congress. In the meantime, President James Madison asked Clay to serve as one of five American envoys—John Quincy Adams, Albert Gallatin, James A. Bayard, Sr., and Jonathan Russell—to negotiate an end to the war with a British delegation in Ghent.

In Belgium, the ebullient Clay played in earnest, often staying out all night, gambling and drinking to excess. His wanton behavior annoyed his more staid colleagues and damaged his otherwise high political reputation. After agreeing on a peace treaty that returned the warring nations to status quo ante bellum, which meant that the document failed to address any of the issues that caused the war in the first place, Clay returned to Congress, held the speakership once again, and began to put together the political components of what would become his “American System,” arguing for a high protective tariff to encourage domestic industry, a charter for a strong national bank (that is, a continuation of Hamilton’s Bank of the United States), and government support of internal improvements (roads, canals, steamboats), all of which he saw as steps to improve American unity, prosperity, and, in particular, Western progress. Clay promoted his American System not only for what he believed would be the benefit of the entire nation but also for the sake and well-being of his constituents—Westerners whose nationalistic and patriotic propensities soared just as high as his own.

(Sarin Images (Granger))

(Smithsonian American Art Museum)

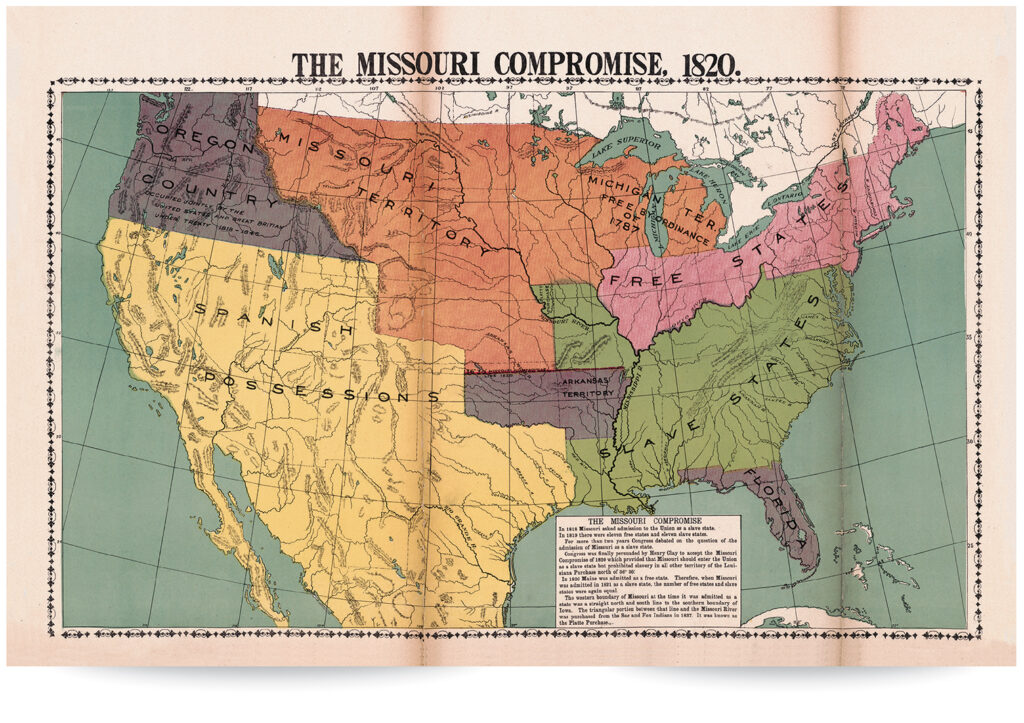

But Clay, who was immensely popular in Kentucky and the Old Northwest, could not avoid making political enemies. Clay opposed nearly every policy advocated by President James Monroe and his administration. His forceful and capable wielding of political power as Speaker of the House earned him respect, but also the disdain of friends and foes alike. He redeemed himself, however, by playing the mediator during the political battle that erupted in Congress over the admission of Missouri into the Union.

Privately Clay opposed slavery in Missouri, but in the House of Representatives he worked selflessly and tirelessly for compromise, a sign of his Western practicality and commonsense approach to overcoming political standoffs. He did not, as many have assumed, frame the basic provisions of the compromise, but he ensured—sometimes using questionable parliamentary tactics—that the separate legislation to admit Maine as a free state and Missouri as a slave state passed in the House.

Clay’s role in the Missouri question won him national acclaim. The president of the Second Bank of the United States, Langdon Cheves, lavished him with praise: “The Constitution of the Union was in danger & has been Saved.” In Missouri, the state’s new U.S. Senator, Thomas Hart Benton, called Clay the “Pacificator of ten millions of Brothers.”

His skill at forging compromise became a hallmark of his political style and character. As early as 1813, he had declared his view that “the true friend to his country, knowing that our Constitution was the work of compromise, in which interests apparently conflicting were attempted to be reconciled, aims to extinguish or allay prejudices.”

(Library of Congress)

Decades later, as he brokered the legislation in Congress that would become the Compromise of 1850, he said: “I go for honorable compromise whenever it can be made. Life itself is but a compromise between death and life, the struggle continuing throughout our whole existence, until the great Destroyer finally triumphs. All legislation, all government, all society, is formed upon the principle of mutual concession, politeness, comity, courtesy; upon these, everything is based. …Compromise is peculiarly appropriate among the members of a republic, as of one common family.”

At the same time, his adroit ability as an orator boosted his fame and his popularity. Some regarded him as the “Cicero of the West,” thus placing him within the great pantheon of exceptional ancient orators. A colleague in the House of Representatives heard Clay deliver a four-hour speech and drew a memorable portrait of the great speaker in action: “His mode of speaking is very forcible—He fixes the attention by his earnest & emphatic tones & gestures—the last of which are however far from being graceful—He frequently shrugs his shoulders, & twists his features, & indeed his whole body in the most dreadful scowls & contortions—Yet the whole seems natural; there is no appearance of acting, or theatrical effect.”

In 1821, after the close of the Sixteenth Congress, Clay resigned his seat and returned to Lexington, where his personal finances lay in considerable disarray, mostly caused by the Panic of 1819. Two years later, after reestablishing his financial solvency, Clay won reelection to the House and regained his seat as speaker. He succeeded in advancing the cause of the American System, shepherding legislation through the House for an extension of the National Road beyond Canton, Ohio, and for a new protective tariff that raised custom duties, much to the consternation of Southern opponents. Almost from the moment he returned to Washington, he began running for the presidency.

Competing in a field of four (the others were John Quincy Adams, William Crawford of Georgia, and Andrew Jackson) in the election of 1824, Clay was the odd man out—a Westerner, like Jackson, but one who lacked strong support in the Southern slave states. He came in fourth, but none of the other candidates won a majority of the electoral votes, so the election went to the House of Representatives, in adherence to the Twelfth Amendment to the Constitution. As speaker, Clay decided to vote for Adams, who won on the first ballot.

This image was taken circa 1850, not long before his 1852 death.

(National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

When Adams appointed Clay Secretary of State, Jackson and his followers cried foul and accused the president and his cabinet nominee of having entered into a “corrupt bargain” before any votes were cast in the House. It is unlikely that Adams and Clay made a deal before the House could decide the presidential election, but even if no explicit words were spoken or no handshake occurred between the two men, they each understood that Clay would vote for Adams and that the latter would thus feel obliged to reward the Kentuckian for his support. Whatever the case, Clay’s acceptance of the nomination and his tenure as Secretary of State haunted him for the rest of his political career, not because he had engaged in corruption but because the public believed that he had.

All things considered, he proved to be a mediocre Secretary of State. Clay’s temperament did not fit well with the requirements of an administrative position. Despite his celebrated affability, he kept making enemies, stepping on toes, offending his allies, and rubbing nearly everyone the wrong way. At the end of Adams’s term, Clay took to the stump to campaign for the president—something that no cabinet member had ever done before. Jackson, who had once more thrown his hat into the ring, attacked Adams and Clay relentlessly, keeping the epithet of bargain and corruption alive. In the end, Jackson won the presidency in 1828, and Clay was out of a job. He returned to Ashland, picked up his law practice, and plotted his return to politics. His eye was on the presidential election of 1832. In 1831, the Kentucky legislature obliged him by electing him a U. S. Senator, a political post he no longer scorned. Clay assumed a leadership role in the National Republican Party. In Washington, he opposed Jackson with fierce determination and took a stand to support the Second Bank of the United States, which Jackson succeeding in eliminating during his first term by vetoing a bill to recharter the bank, claiming that it was an aristocratic and monarchial institution created to supply exclusive privilege and other benefits to the rich.

(Library of Congress)

(National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

The Bank War, as the political contest came to be called, took center stage in the election of 1832. Clay ran a spirited campaign, but he could not overcome the breadth and depth of Jackson’s huge popularity. Nevertheless, Clay continued his leadership of the National Republicans, who soon changed their name to Whigs, the opposition party to King Andrew I. Even so, Jacksonian democracy ruled the day, and Clay’s attempts to push his American System in the Senate came to nothing. Instead, Jackson vetoed the Maysville Road Bill, which proposed extending the National Road into Kentucky.

In the meantime, a sectional crisis—far worse than the Bank War because it threatened the survival of the Union itself—descended onto the shoulders of the nation, this time precipitated by South Carolina’s nullification of the Tariff Act of 1828, an action taken in 1832 on the basis of John C. Calhoun’s theory of nullification, which held that a state possessed the constitutional authority to abrogate any federal law it disliked.

Well-known is President Jackson’s forceful response to South Carolina and his equally electric condemnation of the nullifiers. After asking Congress for a Force Bill to threaten South Carolina with military invasion if necessary, Jackson sought to avoid such a calamity by also requesting Congress to pass a tariff more acceptable to Southern interests. Into the breach stepped Henry Clay, the Great Pacificator. He worked behind the scenes, lining up crucial support for a compromise from Southern ultras (including Calhoun) and Northern pro-tariff manufacturers. Clay put together a compromise measure for a new tariff that would gradually lower rates over a period of nine-and-a-half years to a uniform 20 percent ad valorem. On March 1, 1833, Congress passed Clay’s compromise tariff and Jackson’s Force Bill together. The nullification crisis was over.

Clay was committed not only to the principle of compromise but also to the idea of Union. Yet, like many Westerners (including Abraham Lincoln) and Americans in general, Clay’s adherence to the Union came less from an ideological commitment to Union as a political idea and more from a visceral, emotional love for the Union as a unique thing in the world. Nowhere else in the world could such a federation of separate provinces (practically nations in their own right) be found. At the simplest level, the Union was something historical and something tangible, something to be loved with one’s heart, not with one’s head.

In the immediate aftermath of the tariff dispute and the consummation of the compromise Tariff of 1833, Henry Clay’s reputation soared even higher than before. But, as the Age of Jackson advanced, despite all the disagreements over tariffs, slavery, antislavery, and banks, Americans were nevertheless gaining more sophistication about how they perceived their political leaders and greater understanding of the forces that motivated men like Henry Clay. For the applause he received, many wondered just how much of him was selflessly devoted to the Union and how much was simply lust for political distinction and personal aggrandizement. To some, he was the “Savior of the Union.” To others, he was “a most precious scoundrel.” It is hardly surprising that Clay’s greatest popularity could be found in the West, among people who thought of him as their own. To Westerners, Henry Clay was “the Star of the West.”

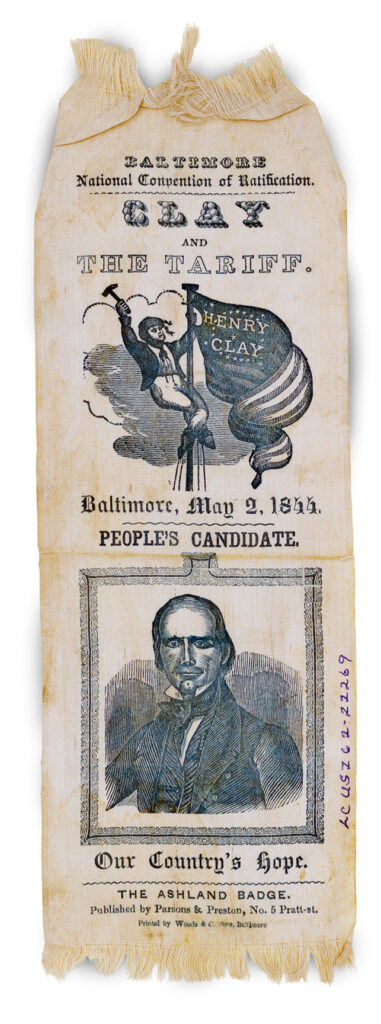

(Library of Congress)

(National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

Westerners set great store by him, relied on him, looked to him to keep their section advancing toward a bright horizon of progress and protect the Union from being torn to pieces by pro-slavery apologists and antislavery proponents. Over and over again, his supporters in the West nominated him as a presidential candidate, but that prize eluded him, much to his own disappointment and that of those who loved him so dearly. His bad luck on the national political scene, however, never discouraged his dedicated followers.

It did, however, delight his enemies. “Harry the Available,” they called him derisively, but Clay put up a good front and continued in the Senate to serve Kentucky, his region, and the Union as best he could. Westerners found comfort in Clay the man and Clay the legend. At times in Congress, he was arrogant, cruel, domineering, jealous, and irritable, but his adherents in the West heard little about his less attractive traits unless they happened to read an anti-Whig newspaper, which they knew already could never be trusted to tell the truth. On the contrary, Westerners trusted Clay and never believed what his opponents might say about him. To them, Henry Clay was “the help and the hope of the West.”

In the years that followed Clay’s brilliant success in 1833, Westerners like Abraham Lincoln watched him display his formidable sagacity and shrewdness in the political arena and studied him as a political exemplar, the man in public office most worthy of emulation. In time, Abraham Lincoln came not only to admire Clay and his Whig politics, but held his fellow Kentuckian in such high esteem that he called the Great Compromiser the “beau ideal of a statesman.” Clay, said Lincoln, was someone he had supported “all my humble life.” Lincoln was not alone in his sentiments. Lincoln never met Clay, but he did see him deliver a speech once in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1847.

But Clay’s great powers could not last forever. At home, his beloved mansion, Ashland, began to crumble when its bricks became so porous one could stick a finger in them. The implacable deterioration of Ashland was a fitting metaphor for what Clay was witnessing, experiencing, and trying to remedy as his country drifted through the decades, suffering its own share of sudden fissures, impermanent mends, and unrelenting declension—all the result of the South’s ceaseless demands for political accommodations that would protect slavery forever, even while the turmoil over the peculiar institution weakened the ties that once had held the nation firmly together in a Union that many Americans, North and South, East and West, truly hoped would be perpetual.

After Clay’s unsuccessful attempt to obtain passage of the Compromise of 1850, a single piece of legislation—called an “Omnibus Bill”—with eight disparate parts, he let Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, a Democrat, push the compromise through Congress as separate bills. For a short time, the Compromise of 1850 quieted the Southern extremists who had begun shouting for secession. In the meantime, Clay grew weak and ill. Death, rather than Life, had caught up with the Great Compromiser. On June 29, 1852, Clay died of tuberculosis in a Washington hotel. He was 75. With him—although no one could see it at the time— the Whig Party died, too.

(University of Kentucky Libraries)

On July 6, Lincoln delivered a lengthy eulogy on Clay at the Hall of Representatives in the Illinois State Capitol. For this memorial gathering, Springfield businesses were closed, citizens stopped their normal routines, “and everything announced the general sorrow at the great national bereavement.” In Clay, Lincoln found the essence of America in his rise from poor family circumstances to one of the greatest political leaders in the country. “Mr. Clay’s lack of a more perfect early education, however it may be regretted generally, teaches at least one profitable lesson; it teaches that in this country, one can scarcely be so poor, but that, if he will, he can acquire sufficient education to get through the world respectably.” Needless to say, Lincoln could have been describing himself and his own path in life. For all his great contributions during his lifetime, said Lincoln, the nation should be more grateful for how Clay stood firm as a defender of the Union: “In all the great questions which have agitated the country, and particularly in those great and fearful crises, the Missouri Question—the Nullification Question, and the late slavery question, as connected with the newly acquired territory, involving and endangering the stability of the Union, he has been the leading and most conspicuous part.”

In Kentucky today, Clay is less remembered than he should be and less a household name than Senator Mitch McConnell. Kentucky’s other U.S. Senator, Rand Paul, takes pride in occupying Henry Clay’s Senate desk. But even Daniel Boone, never accomplished as much as Clay did. He served his constituents well by elevating Kentucky’s political prestige on the national stage. At the same time, he served his country with love and fidelity, nobly earning another nickname, the “Savior of the Union.” He was—and remains—one of the greatest U.S. Senators this nation has ever had, this man who deeply loved the Union, this Henry Clay, the Star of the West.

Glenn W. LaFantasie is the Richard Frockt Family Professor of Civil War History Emeritus at Western Kentucky University. He has written often for American History.

Clay’s Slavery Compromise

No matter how passionate Henry Clay felt about the Union, his was a Union in which whites alone enjoyed the blessings of liberty. But Clay’s emotion for the Union was a white man’s concupiscence. “I am,” pronounced Clay, “no friend of slavery. The searcher of all hearts knows that every pulsation of mine beats high and strong in the cause of civil liberty. . . . But I prefer the liberty of my own country to that of other people; and the liberty of my own race to that of any other race. The liberty of the descendants of Africa in the United State is incompatible with the safety and liberty of the European descendants.” Clay preferred to dream about colonization, although as a practical measure no one could afford to buy the enslaved their freedom and cover the costs of shipping them to Liberia, Africa.

(Sarin Images (Granger))

This story appeared in the 2024 Winter issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.

[ad_2]

Source link