[ad_1]

The Vulcan rocket, built by United Launch Alliance in Denver, Colorado, lifted the first of ten planned commercial US Moon missions into space on 8 January.Credit: United Launch Alliance (ULA)

Update: A few hours after the successful launch of the Peregrine lunar lander mission, Astrobotic reported issues with the spacecraft that might prevent it from reaching the Moon. The company is still assessing the situation. Nature will have coverage when further information is available.

A private robotic spacecraft launched from Florida today, aiming to become the first US mission to land on the Moon since 1972. Among its 20 payloads are five scientific instruments built by NASA, which hopes the mission will open a new era in lunar research.

Private companies are flocking to the Moon — what does that mean for science?

The launch is the first of at least ten planned through NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) programme, in which the agency pays private companies to deliver scientific instruments to the Moon’s surface. If the programme succeeds, NASA will essentially be outsourcing future robotic lunar missions to private companies — a sort of Uber Eats delivery for Moon science.

NASA is aiming for an average of two CLPS flights each year, but as many as six could happen in 2024. “You’ll see progressively more complex science as the commercial community demonstrates what they are capable of,” says Chris Culbert, programme manager for CLPS at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

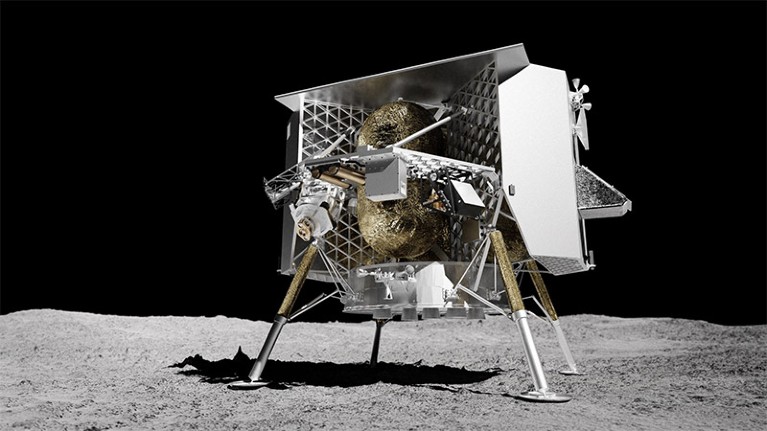

Today’s launch is just the first step in the difficult process of landing on the Moon. The spacecraft, which is called Peregrine and was built by the company Astrobotic in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, still has to successfully enter lunar orbit and then touch down safely. The landing attempt is planned for 23 February.

Sticking the landing

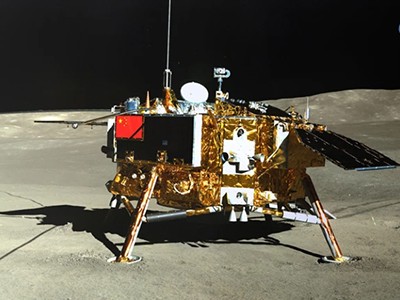

The lunar surface is littered with debris from failed landing attempts. Only the Soviet Union, the United States, China and India have successfully achieved soft landings on the Moon; no private company ever has. A company from Israel crashed its private mission in 2019, and another from Japan did the same last year. The next lunar landing attempt will take place on 20 January, when the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency aims to place its Smart Lander for Investigating Moon mission, which launched in September, in a crater named Shioli on the Moon’s near side.

Peregrine is headed to an area known as Sinus Viscositatis, or the ‘Bay of Stickiness’, which is named for nearby rock domes that seem to have formed from viscous lava. If the 2-metre-tall spacecraft lands successfully, it will start conducting science with a variety of instruments from NASA and others. Among the non-NASA payloads are a set of tiny rovers from Mexico, which will be Latin America’s first lunar mission, and a detector from Germany that will measure radiation levels on the lunar surface, to better understand what future astronauts might be exposed to.

The Peregrine lander from Astrobotic in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, sits on the lunar surface in this artist’s illustration.Credit: Astrobotic

The five NASA instruments on board, paid for in a US$108-million contract, include three that will hunt for volatile elements, such as water. One is a mass spectrometer that will measure the composition of volatile substances in the soil and atmosphere, including in the lunar dust kicked up by Peregrine during landing and by the roaming mini rovers. It will take observations about twice a minute, providing a detailed view of how volatile composition changes over time, says Barbara Cohen, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Another instrument will count neutrons to measure how much water is present in the lunar soil. All three instruments aim to analyse how volatile molecules move around on the lunar surface — including how they are transported to the Moon’s poles, where they are frozen in dark craters. In particular, the water in the craters could serve as a potential resource for future astronauts.

Peregrine also carries non-scientific payloads, including art and educational projects, for paying customers. The most controversial are cremated human remains destined for the lunar surface, provided by two companies that aim to memorialize people in space. The Navajo Nation has lodged a complaint against putting the ashes on the Moon, describing it as desecration of a celestial object that is sacred to the Navajo people. NASA apologized to the Navajo Nation after landing the ashes of planetary scientist Eugene Shoemaker on the Moon in 1999. The agency has a meeting planned with Navajo leaders, as well as with the US Department of Transportation, to discuss next steps.

John Thornton, the chief executive officer of Astrobotic, says the company has aimed to make space accessible to people around the world. “We are really trying to do the right thing, and I hope we can find a good path forward with [the] Navajo Nation,” he says.

Growing pains

The next CLPS mission to take flight after Astrobotic’s will be one from Intuitive Machines in Houston, Texas, which aims to launch in mid-February and land in the Malapert A crater near the lunar south pole. Because the Intuitive Machines lander is travelling a different trajectory than Peregrine, it could actually land on or before 22 February, which would beat Peregrine to the surface. NASA has instruments on board the Intuitive Machines lander to study how exhaust from the rocket interacts with the surface during landing, among other things.

The agency is planning to send astronauts to the lunar south pole in the coming years to search for resources such as water ice. It says that some of the CLPS missions can test science and technology needed for that exploration, such as an ice-drilling rover set to launch as early as November.

Moon mission failure: why is it so hard to pull off a lunar landing?

The CLPS programme has had some growing pains, including delays that pushed its first launch back by two years. One of the companies originally awarded a launch slot went bankrupt, cancelling its mission. And landers have had to be reconfigured to accommodate changes as designs evolve. For instance, Astrobotic discovered that it needed more leeway in how much mass it put aboard Peregrine, so five NASA payloads that had been planned for Peregrine got booted to later CLPS missions.

For those who have worked for years on payloads flying aboard Peregrine, today’s launch is a major milestone. “After so many years of extremely heavy work, it is in a sense the culmination of a childhood dream,” says Gustavo Medina Tanco, a physicist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City, who leads the mini-rover project. And yet, he adds, “space is a risky business, and there are many things that can go wrong at any one of innumerable parts, components and stages”.

Source link