[ad_1]

Pulse oximeter can give inaccurate oxygen readings for people with dark skin.Credit: Afolabi Sotunde/Reuters

Growing evidence1 shows that critical devices for measuring blood-oxygen levels can be inaccurate in people of colour. Now the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) plans to propose that companies conduct more stringent evaluation of the devices, called pulse oximeters, before applying for agency approval.

The proposal, which the agency has not yet formally announced, calls on manufacturers to increase the devices’ accuracy and to boost the number of people on which the devices are tested. The agency also wants companies to test the devices on people whose skin colours span the entire range of a specific colour scale. FDA scientists presented the proposal at a meeting of an independent advisory committee on 2 February.

Researchers who have been studying the performance of the devices and resulting health disparities for years applaud the FDA’s efforts. “The bar was set so low with the regulatory guidance up until now that there’s low-hanging fruit that can be addressed,” says Michael Lipnick, a global health specialist at the University of California, San Francisco.

Vital device

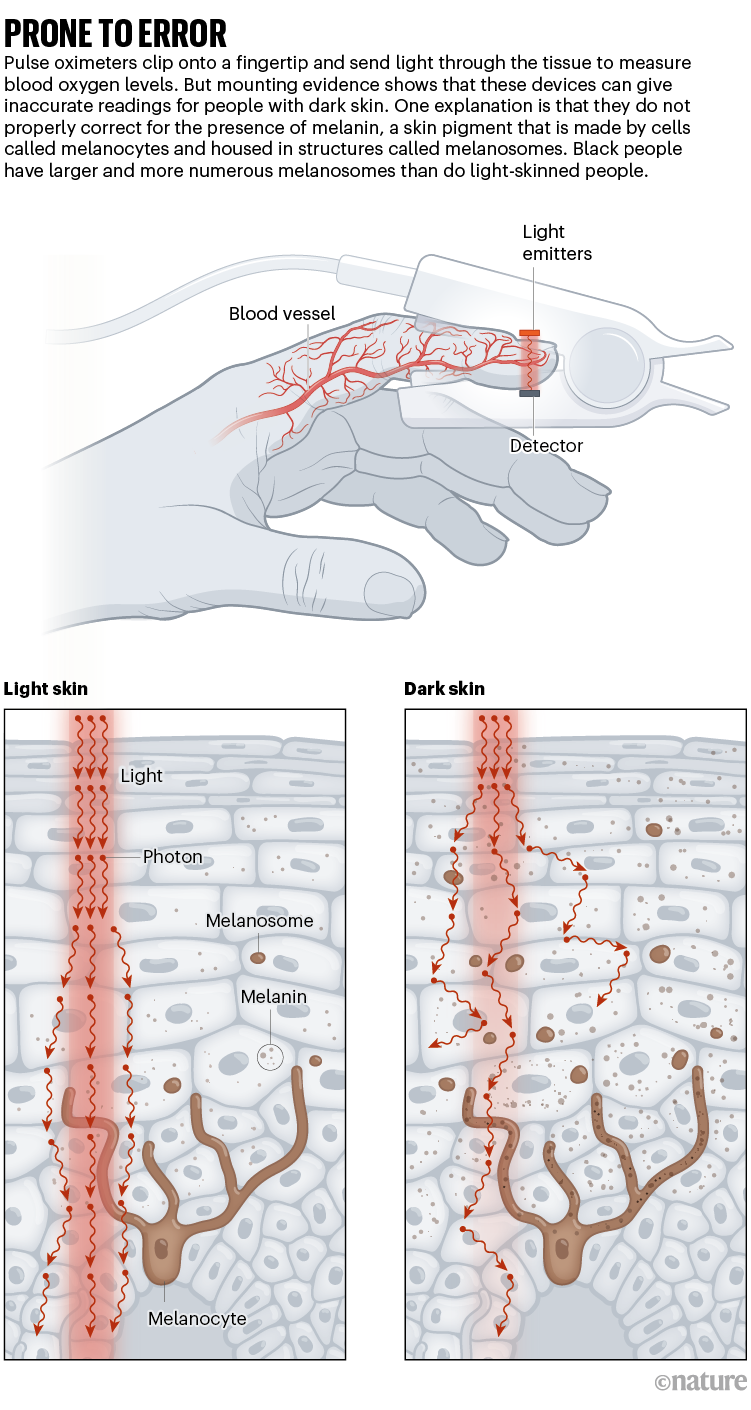

After being clipped onto a fingertip, a pulse oximeter shines light through the digit and measures how much light is absorbed by the oxygen-carrying molecule haemoglobin, giving a reading of blood-oxygen saturation. The measurement, considered one of a person’s ‘vital signs’ alongside heart rate, can give physicians quick insight into a person’s health.

But melanin pigments in dark skin can interfere with the devices. As a result, the oximeters can indicate oxygen saturation values higher than the those derived using the gold-standard method of measuring oxygen levels in blood taken from an artery, especially in people with low blood-oxygen levels.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, studies2,3 found that the devices’ overestimation of oxygen levels can lead to less treatment for people of colour, especially in hospitals that use strict blood-oxygen cut-offs to determine who is eligible for care. “Nobody appreciated that even these small biases could lead to enormous healthcare disparities,” Lipnick says.

These disparities have led researchers and advocacy groups to demand that the FDA ensure that the devices, which historically been calibrated on people with light skin, are accurate in people with dark skin. They have called on the agency to revise its current guidelines — which were published in 2013 — for manufacturers seeking approval for their devices. Those guidelines stipulate that the devices should be tested on at least 10 people, at least 15% of whom must be “darkly pigmented”.

Fingertip oxygen sensors can fail on dark skin — now a physician is suing

At the advisory committee meeting, FDA scientists instead proposed that companies test the devices on at least 24 people whose skin colours span the entirety of the Monk Skin Tone (MST) scale, a 10-shade scale that describes human skin colour. This is an upgrade, says Kimani Toussaint, an optics specialist at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, because “darkly pigmented” is subjective. An increase in the number of people tested will also help the FDA to evaluate whether a device’s performance differs with skin colours, he says.

Real-world testing

But some advisory-committee members, such as Rachel Brummert, a medical device safety advocate based in Charlotte, North Carolina, questioned whether 24 people would be sufficient. And other scientists say they wish the proposed guidelines recommended that manufacturers test their devices in real-world conditions. “Ideally, the FDA would take a more aggressive step to make sure these devices are evaluated in clinical settings,” says Ashraf Fawzy, a pulmonologist and critical care physician at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

In a statement, the FDA responded that it will continue to research improvements to pulse oximeters and that the agency places a “high priority” on ensuring that pulse oximeter performance is is “equitable and accurate for all U.S. patients.”

But more research is still needed to understand how skin colour interacts with other variables, such as how much blood flows to the fingers, Lipnick says. And most studies on the topic are based on self-reported ethnicity or skin-colour data; he and his colleagues are now evaluating the performance of the devices using the MST scale, and investigating whether the MST scale is the best measure to use for this purpose.

Costs and benefits

The debate highlights the tension the agency faces: it seeks to improve the accuracy of the devices while taking care that the additional testing it recommends isn’t overly cumbersome. Nor can the agency suddenly pull the devices from the market when there are no replacements and “such a large volume of patients benefitting from the devices”, says Yadin David, a biomedical engineering consultant in Houston, Texas, who chairs a separate FDA advisory committee on medical devices.

Confronting racism in Black maternal health care in the United States

There are other solutions beyond taking the devices off the shelves, says Michael Sjoding, a pulmonologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He hopes that data about the devices’ performance are made more readily available to potential purchasers, such as hospital systems, so that they can “weigh the data when they’re making purchasing decisions”.

Lipnick says this debate’s implications will reverberate around the world, especially in low- and middle-income countries that still face challenges accessing these devices. If companies find it difficult to comply with new standards, “it could result in products going off the market or prices going up”, he says.

The FDA has not indicated if and when it would move forward with the proposed changes, nor when the changes would go into effect. The agency typically publishes draft proposals and solicits feedback from the public before finalizing guidance. Sjoding hopes changes are implemented soon: “The longer these changes aren’t made, the longer that patients are put at risk,” he says.

Source link