[ad_1]

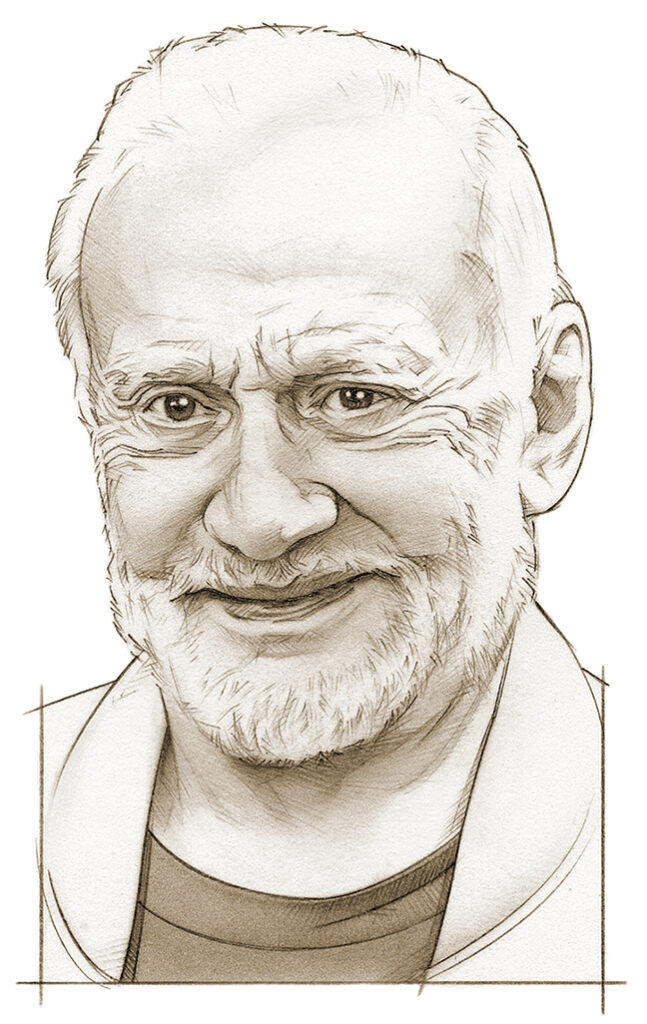

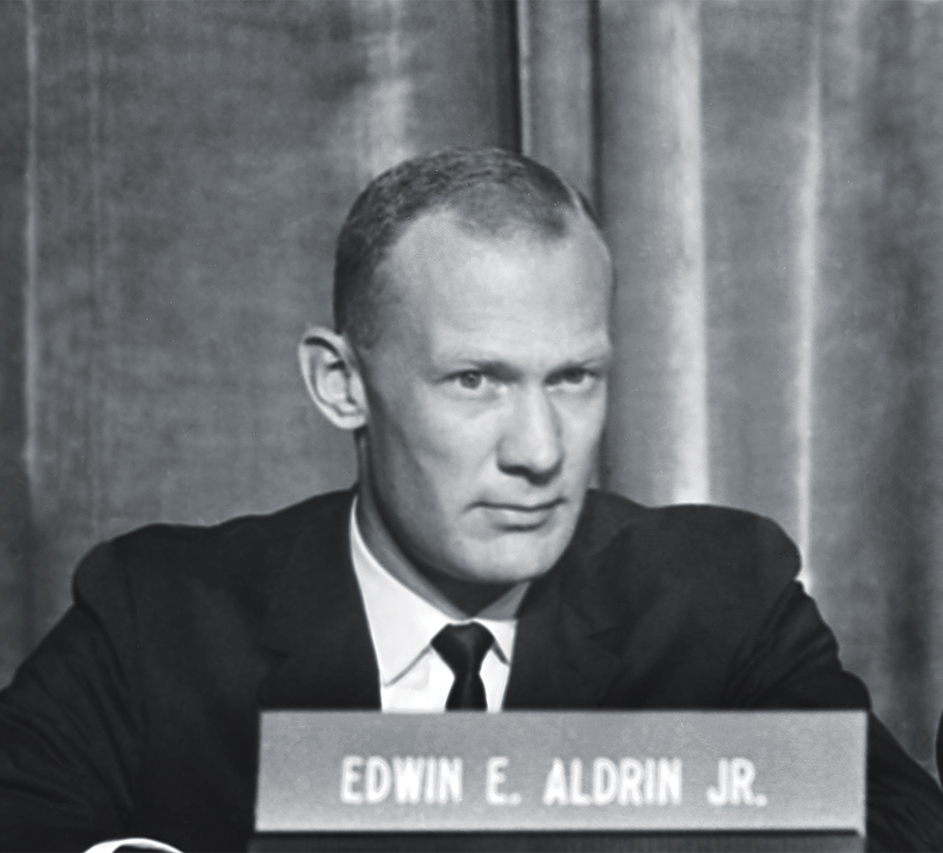

(Randy Glass Studio)

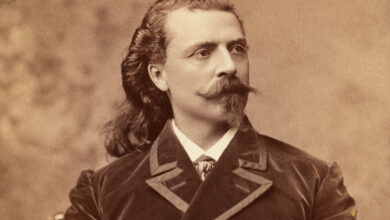

When Military History sought an interview with Buzz Aldrin, he initially demurred. The second human being ever to walk on the surface of the Moon—on July 21, 1969, as a crew member of Apollo 11—he finds that journalists seldom want to discuss anything else. But Aldrin’s career spans much further. A graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, he was commissioned into the Air Force at the outset of the Korean War. Flying the North American F-86 Sabre for the 16th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron, Aldrin completed 66 combat missions and downed two MiG-15 jets. After the war he earned a doctorate in astronautics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Aldrin walked in space as a Gemini astronaut before flying to the Moon with Apollo. Today, the 93-year-old Air Force brigadier general remains a strong advocate of the space program, particularly of planned missions to Mars.

What made you select the Air Force after graduation from West Point?

I wanted to fly and had always wanted to fly. I took my first flight at age 2 with my father and never looked back. Flying was exhilarating. We [graduates] knew the nation would need pilots, so we signed up.

What was it like flying the cutting-edge F-86 Sabre?

Fast in a dogfight—and I was in a couple of those—and gratifying, because the plane handled well, although my gun got jammed in one encounter, and on another occasion I had a frozen fuel line. But the plane was a jet, and we liked the idea of flying jets. They got you higher and faster, and we all liked that.

How did the MiG-15 match up in your two recorded Korean War shootdowns?

The MiG-15 was a fast plane, and they had good pilots. The pilot ejected in the first one, which was filmed by the nose camera [of my Sabre].

(U.S. AIR FORCE)

Your second kill entailed a difficult dogfight. Tell us about that.

Not a lot to tell, but you can see photos of it. My gun jammed on my first lock, so I had to be steady, stay with him, get the lock again and then fire. He, too, ejected, which was good for him. Dogfights are all-consuming—they happen fast. Nothing about a shootdown is easy, but when you return alive you feel glad you returned, glad you could do what you were supposed to.

What was it like flying the F-100 Super Sabre equipped with nuclear weapons?

I will just say, those times—perhaps a bit like these times—were about being prepared. There was tension, but we were always well trained, ready for what might come. We signed up to protect the United States, and so we did. It was as simple as that. We all thought freedom mattered, and we flew to protect it.

A fighter jock with a doctoral degree?

Yes, before selection to NASA’s third group of astronauts, I earned my doctorate from MIT. I wrote a thesis called “Line-of-Sight Guidance Techniques for Manned Orbital Rendezvous.” An understanding of that topic and orbital mechanics proved fortuitous when Jim Lovell and I flew Gemini 12, the last Gemini mission, which required proving the efficacy of orbital rendezvous. As fate would have it, we actually needed to manage part of that process manually, due to computer problems, so the thesis came in handy after all.

(National Aeronautics and Space Administration)

How excited were you to join the space program?

Very. And looking back, I was just fortunate to be selected for Gemini 12 and Apollo 11. I was also blessed to have great crewmates—Lovell in Gemini 12, and Neil Armstrong and Mike Collins in Apollo 11. What can you say? We were all blessed.

Describe the sensation of your free-flight space walk for Gemini.

My longest EVA [extravehicular activity], or space walk, of Gemini 12 was surprising for the beauty and sense of accomplishment that came with it—and because my heart rate apparently stayed low. Someone asked me why, and I really could not say, except that I was honestly having fun.

We must ask, what was it like to walk on the Moon?

In many other venues I have discussed the answer to that question, but suffice to say we had a job to do, and we worked very hard to do it. We did not want to let others down, since so many had worked to make Apollo 11, mankind’s first Moon landing, a success. I called it “magnificent desolation” at the time, and that remains a good description. It was also an honor, and while we trained hard for it, the actual event was exhilarating in small and unexpected ways. We saw our shadow landing, which never happened in simulation. We had to test one-sixth gravity, since that could not be simulated. We had to get experiments out, and one required waiting for a small BB to settle in a cone, which took a while with one-sixth gravity. Neil and I worked together to get the American flag in, which was harder than you might think with only about an inch of Moon dust to plant it in.

Well, it was humbling, gratifying, and I was really honored. I stepped out of the normal advancement sequence flying for NASA. Afterward, I continued to serve, fly and believe in the U.S. Air Force. To be recognized for that—for what I did during and after that special time—was gratifying. I thank all those involved. It meant a lot, and I am happy still when I think about that day.

(Ed Kolenovsky (Associated Press))

You continue to advocate for a manned mission to Mars. Why?

Simple, really: The United States is the leader in human space exploration, and we need to keep reaching outward, expanding and enriching the human experience. That means not resting on our laurels, but going out to Mars, exploring and swiftly creating permanence there—not a touch-and-go, but staying on Mars.

How do you reflect on your achievements in the military and as an astronaut?

We all have our stories and our journey, and mine has been exciting. It was an honor to serve in Korea, with NASA and thereafter with the Air Force. This nation is one of a kind—both a great and good country. Those opportunities came from tens of thousands of other dedicated Americans, and I feel forever grateful for what they did to make my journey possible. So, how do you reflect on all that? You just remind yourself each dawn is precious, and you stay grateful. You keep trying to do whatever you can to keep the greatness and goodness going.

This interview appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of Military History magazine.

Source link