The Miller Bros. 101 Ranch Real Wild West Didn’t Have Buffalo Bill’s Reach, But Its Performers Took Hollywood by Storm

[ad_1]

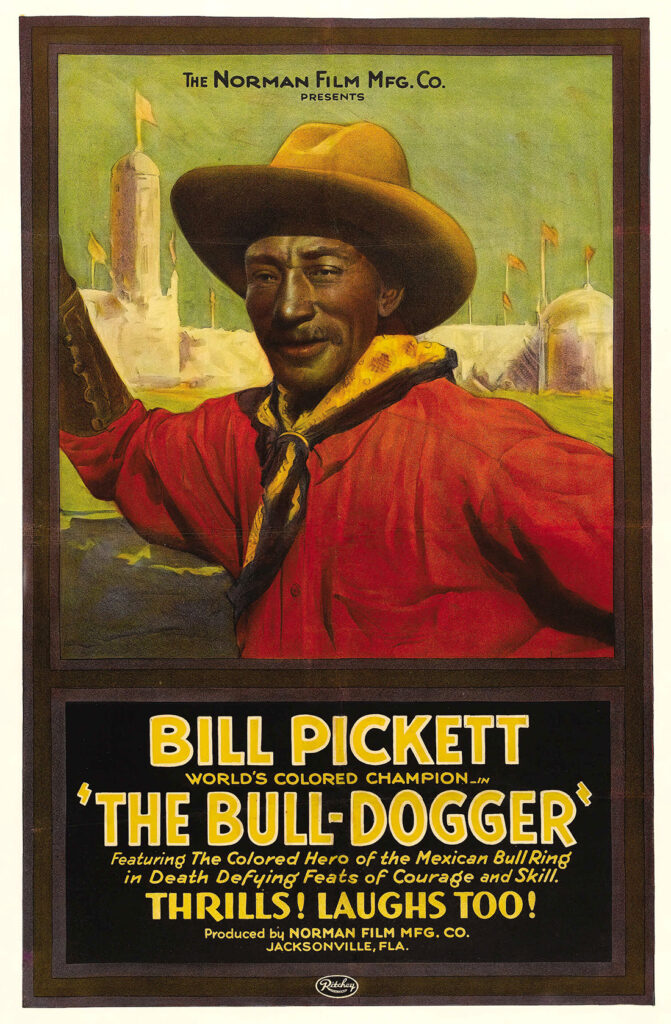

To the disbelief of gaping onlookers in the packed stands at El Toreo, Mexico City’s largest bullring, American rodeo performer Bill Pickett clung to the horns of a massive Mexican bull ironically named Frijoles Chiquitos (“Little Beans”). Watching from a safe distance in the saddle atop jittery horses were cowhand Vester Pegg and siblings Joe and Zack Miller, proprietors of the Miller Bros. 101 Ranch Real Wild West. Matadors, including the famed Manuel Mejíjas Luján (aka “Bienvenida”), also stood by as Bill grappled with the snorting, gyrating wild beast, which Mexican and Spanish bullfighters alike typically fought from a more dignified distance. Funny thing is, Pickett wasn’t even supposed to be there. Days earlier he’d been working one of the Miller family ranches back in Oklahoma.

It was early December 1908, and the Real Wild West had come off a grueling tour of the United States. Instead of heading home to lick their wounds, however, Joe and Zack Miller took the show south of the border. Though still two years from the onset of the Mexican Revolution, that southern neighbor was already in turmoil. The troupe endured several intrusive (and costly in bribes) searches by customs officials before arriving in Mexico City on December 11. The streets of the heavily populated capital were clogged with Roman Catholic pilgrims preparing for the next day’s Our Lady of Guadalupe observance, marking the 1531 visions of the Virgin Mary to believers in that Mexican city. The observance also marked the start of the show’s two-week run at the circus arena in Porfirio Díaz Park.

Low attendance and gouging fines for Pickett’s failure to appear, though “The Dusky Demon” was prominently featured in advertisements, led Joe to telegram brother George, back at the 101 Ranch, with instructions to have Pickett travel down by train immediately. Shortly after the bulldogger arrived and began performing, Joe and the show’s press agent, W.C. Thompson, stopped in at the Café Colón, a popular eatery among matadors and local reporters, where Joe hoped to gin up publicity for the show. When a table of matadors directed their laughter at the gringos, Joe asked what they found so humorous. They told him they had attended the show that afternoon and were unimpressed with Pickett’s antics in the ring, comparing him to a novice bullfighter. An indignant Miller challenged them on the spot to go toe to toe with Pickett in a bulldogging event. On behalf of the group, Bienvenida accepted and agreed to show up at the circus arena at 10 the next morning. But neither he nor any other matador took up the challenge, claiming the arena promoters forbade them from taking any such foolish risk.

After several days of verbal exchanges, challenges and braying newspaper ads, Miller bet the arena promoters Pickett could remain alone in the ring for 15 minutes with their fiercest fighting bull and spend at least five minutes of that time grappling barehanded with the beast, wrestling it to the ground if possible. If Pickett succeeded, the Millers would collect the gate receipts for the day. Joe also made a 5,000-peso side bet. The publicity from his wager and newspaper coverage led promoters to move the bulldogging spectacle, scheduled for December 23, to the far larger El Toreo. Within days Mexico City’s largest venue had sold out.

On the afternoon of the 23rd Pickett trotted into the arena atop his favorite horse, Spradley, to a cacophony of cheers, boos and hisses from an estimated 25,000 onlookers. As the blare of the opening trumpets faded, the gate to the corrals swung wide, and Frijoles Chiquitos stormed into the ring. When the bull saw Pickett and raced across the arena toward him, Bill saw right off that his terrified hazers would be of no use.

Steering Spradley in close to Frijoles Chiquitos, Bill sought to maneuver into position to leap on the bull’s bulging neck. Each time the rampaging beast gave them the slip. Suddenly, the bull swung around and charged rider and horse from behind. Spradley could not evade the rush, and one of Frijoles Chiquitos’ horns ripped open the horse’s rump, causing it to stumble. Taking advantage of the distraction, Pickett dove from the saddle. Locking on to the bull’s horns, he wrapped himself around its writhing neck and rode Frijoles Chiquitos as the crowd rose to its feet in anticipation. The bull tried everything it could to free itself of Pickett, to no avail. For several agonizing minutes it wildly shook its great head, slashing with its horns, as the determined bulldogger clung tight, looking for an opportunity to take the animal to the ground.

Likely bemoaning their decision to bet against the do-or-die Yankee, the crowd turned on Bill and began pelting him with whatever was at hand. Fruit, cushions, rocks, bottles, even bricks rained down from the stands. After taking a rock to the side of his face and a beer bottle to the ribs, a bleeding and dazed Pickett released his iron grip on the raging Frijoles Chiquitos and lay on the arena floor grimacing in pain. Rushing in, his 101 Ranch hazers finally distracted the bull long enough to help Bill to his feet and out of the ring.

The crowd’s delight at Pickett’s failure turned to disappointment on learning he’d made it to the 5-minute mark, thus winning the wager. With his seven and a half minute ride the bulldogger had earned the show a whopping 48,000 pesos (north of $450,000 in today’s dollars), not to mention Joe’s side bet. The day after Christmas the show wrapped up its lucrative run in Mexico City and headed back north. Joe canceled a scheduled show in Gainesville, Texas, and as the train arrived in Bliss, Okla., weary troupe members clapped and cheered at being home. The big payday had helped buffer an otherwise tough financial year, and the show’s future seemed bright.

A Working Ranch

Most Western historians cite 1881 as the year 101 Ranch patriarch Colonel George Washington Miller first seared his brand on cattle. A notorious namesake San Antonio saloon is said to have inspired the brand. Whatever the truth, that first bitter wisp of burnt hide launched a story for the ages, as the 101 was destined to become one of the most recognizable names in both ranching and Western entertainment.

A Kentucky native, Miller fought for the Confederacy in his 20s and moved west after the Civil War, initially settling in southwest Missouri and driving cattle from Texas to the railheads in Kansas. Miller later moved his herds to land leased from the Quapaw tribe in Indian Territory (present-day northeast Oklahoma) while residing just across the border in Baxter Springs, Kan. He cultivated a relationship with the Ponca tribe when it was briefly displaced to the Quapaw Agency. Miller suggested the Poncas settle on land farther west in the Cherokee Outlet. After the federal government forced ranchers out of the outlet in 1893, the Poncas did just that, and Miller leased their land for his operations, setting up headquarters near the tribal hub at New Ponca (renamed Ponca City in 1913). The 101 Ranch ultimately comprised 110,000 acres.

After Miller succumbed to pneumonia in 1903, wife Molly had the ranch turned into a trust, with Joe, Zack and George as equal partners and shareholders. From then on the trio ran the whole shooting match. At the time of their father’s death Joseph Carson Miller was 35 years old, Zachary Taylor Miller 25, and the youngest, George Lee Miller, 21. Each brother developed unique interests and skills, enabling them to divide oversight of the 101 effectively and without rancor. Together they remained focused on realizing their father’s dream to build the nation’s largest and most influential ranch.

(Library of Congress)

The rich soil already grew a range of crops, while livestock included cattle, bison, hogs, poultry and several breeds of horse. The brothers continued to experiment with crops and added an electric plant, a cannery, a dairy, a tannery, a store, a restaurant and several mills. Promoted as the “greatest diversified farm on earth,” the ranch prospered well into the early 20th century.

Of course, oil too played a role. Ernest W. Marland, of Marland Oil Co., spearheaded the search for crude deposits on the family spread and helped form the 101 Ranch Oil Co. That highly successful venture substantially increased the Millers’ profit margin.

All-important downtime served to seed the brothers’ entrance into show business.

(Oklahoma Historical Society)

What became the Real Wild West had its roots in late summer or early fall 1882 in Winfield, Kan., where Colonel Miller, Mollie and their children had recently moved. Miller and hands had just finished a cattle drive up the Chisolm Trail from Texas. Meanwhile, Winfield city leaders were planning an agricultural fair and wanted entertainment. Miller proposed his cowboys put on a roping and riding exhibition, and the event planners enthusiastically accepted his offer. Miller’s “roundup,” as he called it, proved a roaring success.

The business of running a sprawling ranch intervened, and it wasn’t until 1904, a year after Colonel Miller’s death, that the 101 hosted its next roundup. This time it was the Miller brothers’ brainchild.

That year Joe Miller visited the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Mo. While there he and leading Oklahoma newspapermen met with the board of directors of the National Editorial Association, hoping to convince the board to hold its 1905 convention in Guthrie. To sweeten the pot, Joe told the directors the 101 Ranch would host them and put on a big Wild West show in their honor. The board bit and approved the proposal.

The Millers thought it best to prepare for the 1905 event by holding a roundup in the fall of 1904. Pleased with the enthusiastic turnout, the brothers planned the 1905 roundup, which they grandly dubbed the Oklahoma Gala. Dozens of trains were needed to help transport the more than 65,000 people who attended the elaborate opening parade on June 11. It was the largest crowd yet assembled for an event in Oklahoma.

The June gala ended with a reenactment of a wagon train attack by 300 Indians. Gunfire and bloodcurdling screams rose from the arena floor as wagons caught fire and settlers closed with their assailants in mortal combat. More credulous onlookers feared they were witnessing a real massacre. Then, out of nowhere, a posse of cowboys rode to the rescue, guns blazing. As the act drew to a close, the performers gathered at the center of the arena to a standing ovation. The Miller brothers joined the troupe to bask in the crowd’s appreciation.

Over the next two decades the Millers hosted annual roundups at the 101, seating up to 10,000 spectators in an arena just across from ranch headquarters. The program always included roping, riding and bulldogging, as well as Indian dances and other Western cultural offerings. The brothers employed top cowboys from across the region, and Pickett and other well-known 101 Ranch hands went on to stardom in Hollywood Westerns.

The “Show Business Bug”

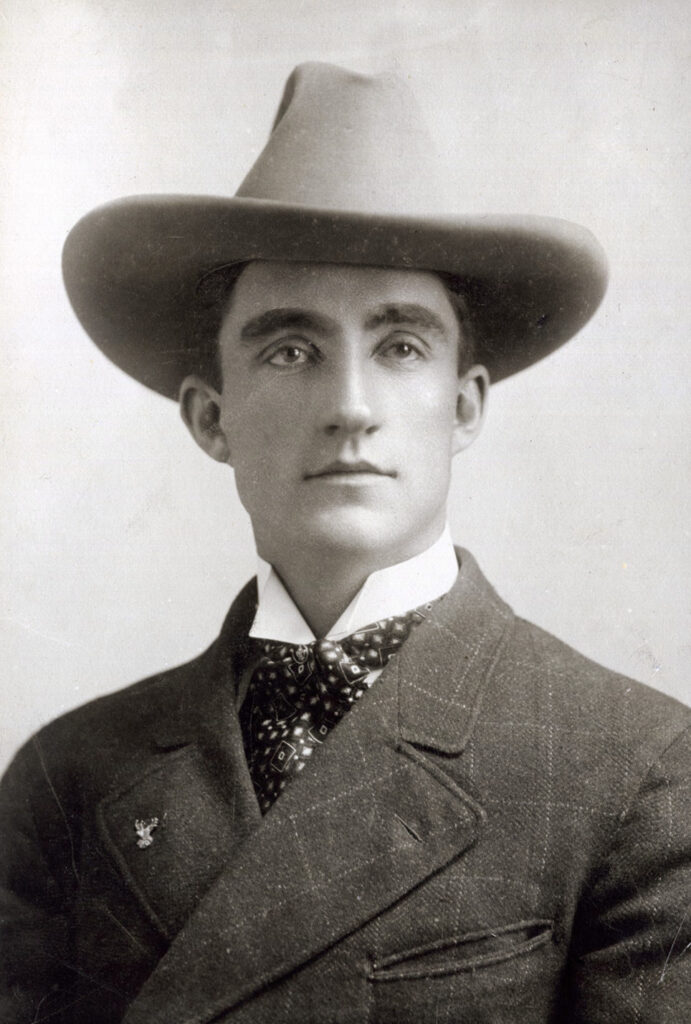

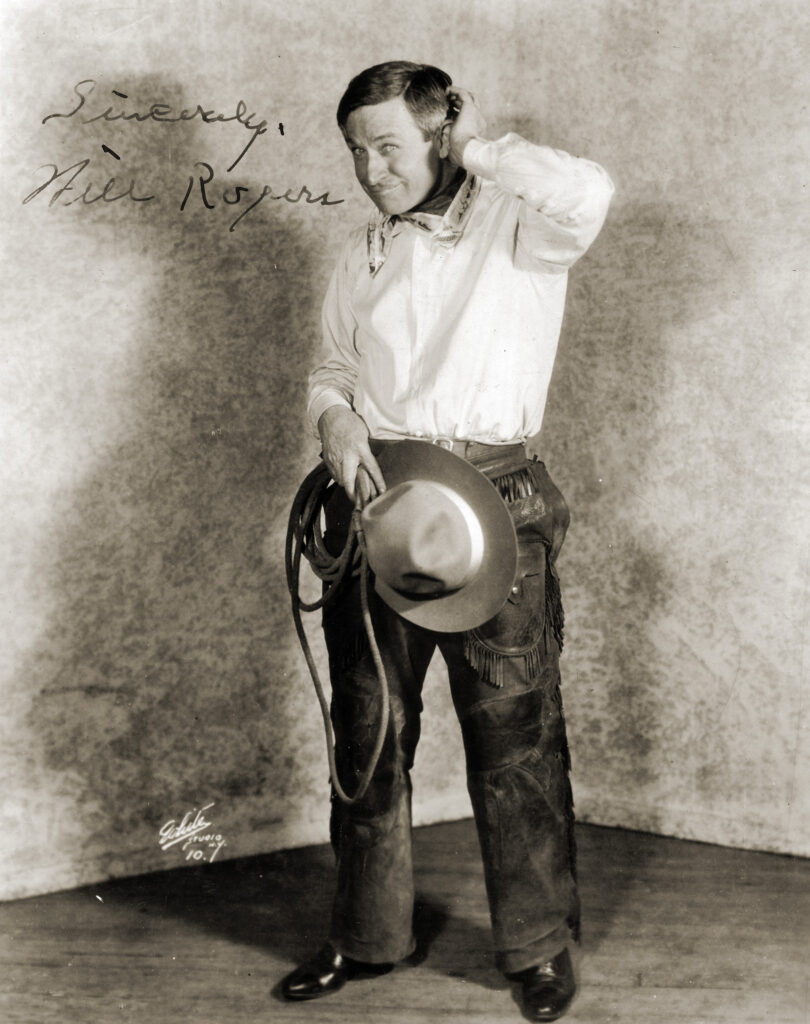

Planning for the June 1905 Oklahoma Gala had another unexpected offshoot, for Joe caught the “show business bug” in a big way. Looking ahead to the June gala, he and Zack arranged to have some of their performers join Colonel Zack Mulhall and his touring Western troupe in a series of shows that April at New York City’s Madison Square Garden. Appearing before packed houses in one the biggest venues of the era gave the brothers an opportunity to learn the production aspects of a touring show. It also afforded their performers rehearsal time for the upcoming gala. Among the Miller hands appearing at the garden was Will Rogers, then a relative unknown. Indeed, Mulhall initially turned down Rogers, who had to enlist the help of the colonel’s wife, Mary, to secure a spot on the program.

It is ironic, then, that while the Madison Square Garden run proved successful for Mulhall, Rogers benefited all the more from his appearance. The turning point came amid the sixth show when a steer got loose and entered the stands. Thinking quickly, Will lassoed the wayward animal and guided it back to the arena floor, saving the day. The publicity generated by his courage, talent with a lariat and wit prompted a shrewd promoter to offer him a starring role, performing his rope acts solo on vaudeville stages in Manhattan.

(Denver Public Library)

Meanwhile, Joe, Zack and their well-rehearsed performers returned to Oklahoma to finish preparations for the gala. Taking a page from Mulhall, the Millers generated a marketing blitz, published in newspapers and spread through contacts nationwide, describing what attendees could expect on June 11. The lineup included bulldogger Pickett, trick rider Lucille Mulhall (the colonel’s daughter), expert horseman and crack shot Tom Mix and a supporting cast of almost a thousand performers, many from the local Ponca and Otoe tribes.

The 101 Real Wild West was one step from becoming one of the most popular traveling Western entertainment troupes of its era.

Taking the Show on the Road

Encouraged by their successful 1905 gala, and at the urging of Oklahoma neighbor Gordon W. “Pawnee Bill” Lillie—who’d already made a name for himself as the founder and proprietor of Pawnee Bill’s Wild West—the Millers took their show on the road full time in 1907. Favorable publicity from an early run in Kansas City, Mo., caught the notice of Theodore Roosevelt. The “Cowboy President” was already acquainted with the Millers from prior visits to their ranch. (On his invitation Mix had ridden in the president’s 1905 inaugural parade alongside Roosevelt’s Spanish-American War “Rough Riders,” sparking a rumor the 101 Ranch hand had been a Rough Rider himself.) Roosevelt persuaded the Millers to bring their show to Norfolk, Va., as part of the Jamestown Exposition. At the close of that 100-day run the exposition promoters helped land the Real Wild West a two-week run at the Chicago Coliseum. The publicity from 1907 led to the busy but grueling 1908 tour, starting at Brighton Beach, N.Y. Through 1916 the Millers and their performers were at the top of their game as crowds grew ever bigger, drawn by a spreading fascination with cowboys, Indians and all things Western.

In 1916 the Millers merged their production with Cody’s arena show and toured as Buffalo Bill (Himself) & the 101 Ranch Wild West Combined, though the nation’s growing involvement in World War I put the tour on hold later that year. Cody died soon after, on Jan. 10, 1917. Going back on the road in 1925, the Real Wild West toured throughout the United States and abroad, traveling to Mexico, Canada, Europe and South America.

(McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West)

(Oklahoma Historical Society)

Through the 1920s, however, the 101 Ranch Real Wild West, Pawnee Bill’s Wild West and other touring shows drew ever smaller crowds, leading to severe financial losses. By then such productions faced stiff competition from the film industry, as well as proliferating circuses and rodeos. Making matters worse for the Real Wild West, Joe Miller died in 1927, followed two years later by the death of brother George. Then came the Great Depression, which drastically cut into profits from the ranch and show. Zack alone could not pull the operation out of its tailspin, and in 1931 the 101 Ranch and its associated businesses went into receivership. A year later much of the land was divided and leased, and authorities auctioned everything of value to cover debts. On Jan. 3, 1952, a nearly destitute Zack Miller died.

Today one may visit the site of the ranch headquarters, though all that’s left are a few weathered buildings, the foundation of the Miller home (known in its prime as the “White House”) and a few historical markers describing what once was. An excellent nonprofit named the 101 Ranch Old Timers Association continues its work to keep the ranch and show legacy alive. Its members support a wonderful museum housed within oilman E.W. Marland’s Grand Home in Ponca City and host annual events and tours for the public. And so the show goes on.

New Mexico–based E. Joe Brown is an award-winning author of novels, short stories and memoirs. For further reading he recommends The Real Wild West: The 101 Ranch and the Creation of the American West, by Michael Wallis, and The 101 Ranch, by Ellsworth Collings and Alma Miller England.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2024 issue of Wild West.

Source link