[ad_1]

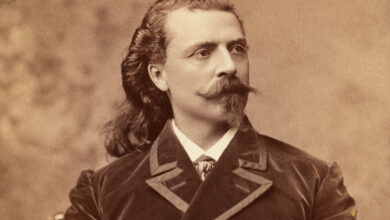

Frenchman Henri Farman was already a celebrated cycling champion, race car driver and entrepreneur when he ordered a biplane from the world’s first airplane factory, Les Frères Voisin. Five months later, in January 1908, he won Ernest Archdeacon’s prize for the first officially observed heavier-than-air flight over a one-kilometer circular course.

A week after making Europe’s first flight outside France (in Belgium), Farman lunched with Wilbur Wright in Paris in June. They got on famously; when Wilbur explained his plans to make demonstration flights in France, Farman replied that he had accepted an offer from a consortium of St. Louis businessmen. He would get $25,000 for touring the United States for 90 days, plus $200 per flight. The organizer was Tom MacMechan, editor of American Aeronaut. “These public demonstrations ought to bring about a great popular realization of the practicability of dynamic flight,” enthused Aeronautics, another aviation journal.

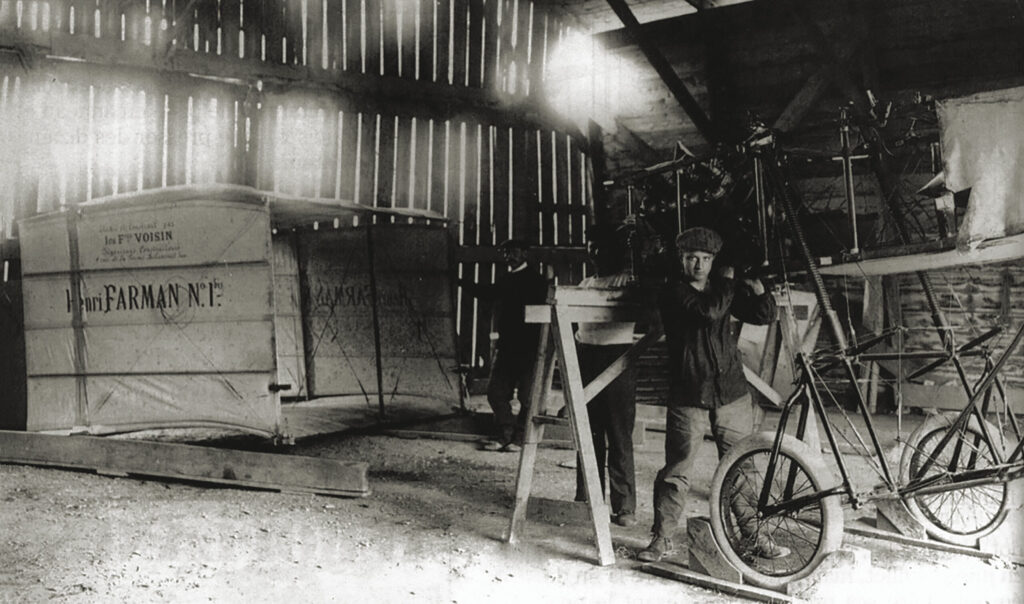

After learning that aviator Glenn Curtiss had flown his June Bug on July 4 to win the $25,000 Scientific American Cup for the first public powered flight in America, Farman crated his Voisin for shipment across the Atlantic. He sailed with his assistant, Maurice Herbster, and his wife, arriving in New York on July 26 to an enthusiastic welcome. Headed by Curtiss, a welcoming committee from the Aero Club of America chartered a tug to escort the Farmans’ ship to the pier, where automobiles whisked them to the Hotel Astor on Times Square.

(Courtesy Reg Winstone)

Farman had become front-page news, where he was hailed as “the world’s champion aeronaut” and “the man with the practical aeroplane.” The military was keen to witness his demonstrations, and with Orville Wright planning test flights for the government at Fort Myer, Virginia, an international contest seemed possible. Farman even challenged Orville to a contest for a $10,000 purse, but Wright declined. Farman was unfazed: “If they consider their machines superior, why don’t they accept my challenge? I could gain much valuable data from a contest, and surely my machine, with its long list of record flights, has at least some points of information for my brother aviators.”

As the venue for his demonstrations, Farman chose the horseracing track in Brighton Beach, New York, which in 1907 had been converted to host 24-hour endurance motor races known as “Grinds.” Farman arranged to remove large sections of an infield fence while he had his crates hoisted onto theatrical scenery trucks and unloaded in the track’s old betting ring. When customs officers did not arrive as expected to examine the contents, Farman sent away his hired stevedores. Then the revenue men finally arrived and Herbster had to recruit a crew of unskilled locals. They dropped one of the crates, damaging the airplane’s tail cell and rudder. Despite the damage, the appraiser declared the Voisin’s new Antoinette V8 engine to be the finest piece of machinery he had ever seen, saying that “all who examined the machine were greatly impressed with its workmanship, which is exquisite.” Farman spend the next day on repairs, reassembling the airframe and installing the engine.

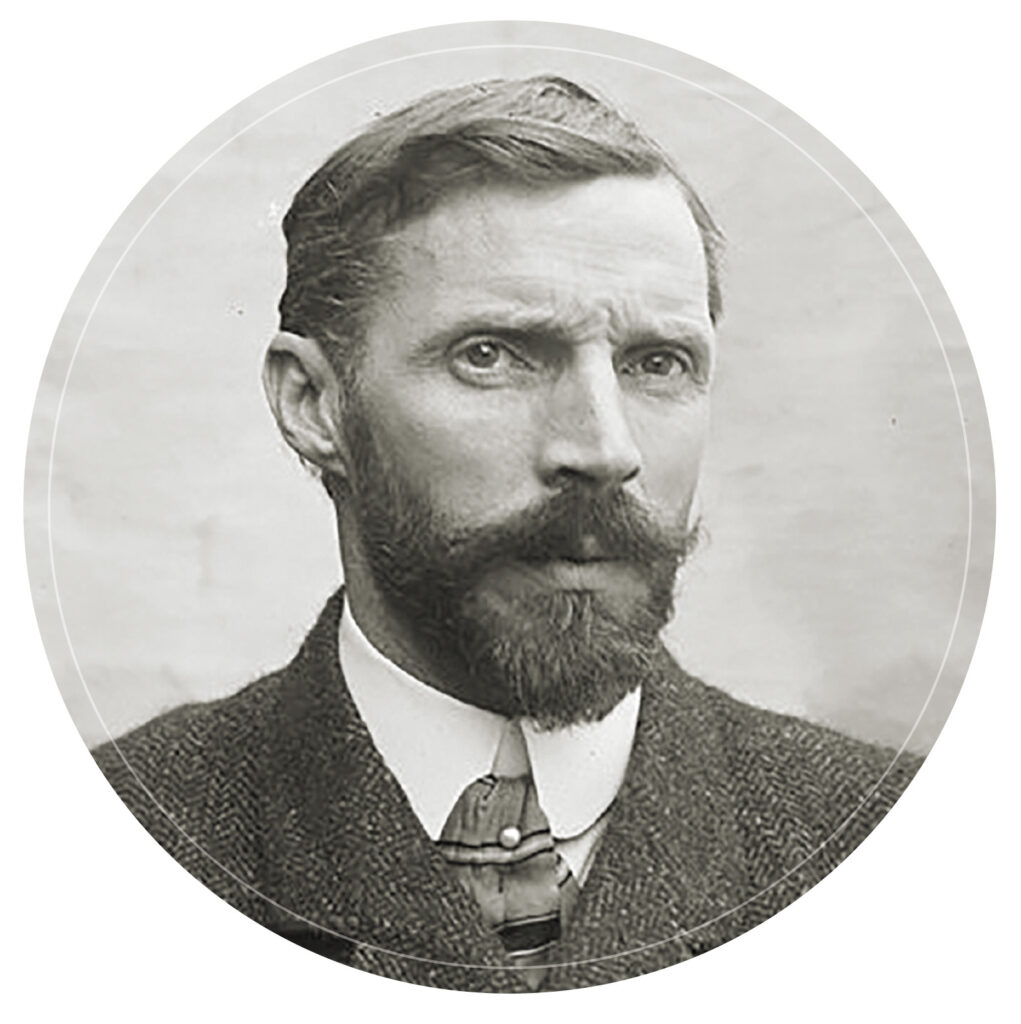

At a banquet at the Astor on July 30 one news account noted that “the ballroom was full of balloonites, with here and there a submarine fiend, an auto crank or a common scientist wedged in among the number.” Charles Manly, the engineer and test pilot for aviation experimenter Samuel Langley, congratulated France on its aviation experimenters and described Farman as “a man destined to do great good for aeronautics and create enthusiasm among millions.” Farman’s riposte was equally gracious to those on this side of the Atlantic: “We foreigners owe credit to Octave Chanute for the basic principles of our apparatus, and to the Wright brothers, pioneers after Mr. Chanute.”

After the guests had consumed a model of the Voisin confected from spun sugar, Farman made a less-than-sweet dig at the secretive and litigious Wrights. “I carry on my experiments in public because that seems advantageous,” he said. “The work is difficult enough, and it is better for others to see what you are doing and for you to see what they are doing, each improving by the mistakes of the other.”

(Courtesy Reg Winstone)

Farman was not alone in resenting the Wrights’ secrecy, even on home turf. The American Magazine of Aeronautics opined, “Farman has perhaps done more, through publicity, to brush away the cobwebs of doubt than the Wrights. Even here, we doubt that the Wrights ever flew, while we read of the Farman’s flights with less astonishment than at the invention of a headacheless booze.” James Means, editor of Aeronautical Annuals agreed, saying, “Owing to the public exhibitions of flights with motor-aeroplanes in France, the Frenchmen are in a fair way to get years ahead of us in aviation, as they did with the automobile.”

“We are disgusted with some American inventors who have been chasing the almighty dollar instead of solving the problems of flight,” railed MacMechan in the American Aeronaut. For impeding the free exchange of ideas, he argued, the Wrights should forfeit their place in history for making the world’s first airplane flight. He added, “After Farman’s flight, there will be no difficulty raising capital to finance the cost of building aeroplanes and conducting experiments.”

First, though, Farman had to get into the air, and that was looking problematic. At only 840 yards, the racetrack was short and it was traversed by ruts and ditches. Ominously, Farman’s promised down payment of $6,000 failed to materialize, so track owner William Engeman was induced to mollify him with cash so the show could go on.

Apart from finances and the small track, keeping the water-cooled Antoinette from overheating was Farman’s main problem. Its “total-loss” cooling system meant the engine water evaporated as it carried heat away, and since the Voisin had a marginal power/weight ratio, the airplane could carry only so much coolant. “If we could carry sufficient water,” Farman said, “we could stay in the air 30 hours as easily as 30 minutes.” Wind was his second concern: “A steady, strong wind is what you want—but if it becomes too strong, great care is needed. Trees and other obstacles can divert the wind. I generally fly 15 feet above the ground—I can fly higher, but never as high as your skyscrapers, although I hope to some day.”

(Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Ever cautious, Farman confided to the Daily Tribune, “When I risk my neck, as every man who mounts an aeroplane is bound to, I am at least certain that I have left nothing undone to make my apparatus as perfect as possible. I take no unnecessary risks—I could soar into the air to any height if my motor would work long enough. But it would be folly to ascend a yard higher than necessary, for the aeroplane is at present a very delicate machine and something may snap at any moment.” He managed the public’s expectations accordingly. “I want to emphasize to the American people that an aeroplane does not fly over the rooftops like a balloon. I hope they will not be disappointed to find that they can view airships without craning their necks.”

On July 31, before his first public show, Farman flew for Aero Club members. According to the New York Times, “Several hundred persons were near the curtained-off part of the betting ring in which the machine is kept when it was pushed out. Then those who watched got some idea of the driving power of the propeller. A mechanician turned the motor over by twisting the blades while five men held the aeroplane, Mr Farman advanced the spark and opened the throttle. The whirling blades shook the shrubbery 60′ away as in a windstorm, while dust clouds were blown up 75′ away.… [T]he airscrew of the Voisin began to revolve swiftly, and the machine moved across the turf for 200 yards. It left the ground, mounted ten or twelve feet in the air and moved along with an easy, bird-like glide. Two-thirds of the way to the eastern extremity of the oval, a group of men with a wagonload of boards were busy covering a ditch. A calf ran about and the crowd infringed. As he bore down on these obstructions, Farman stopped his propeller, while the guiding planes were inclined downward. As the aeroplane neared the turf, Mr Farman let his propeller shoot around for a moment. This made the landing as gentle as that of any creature of the air. It was a delicate piece of airmanship, and the crowd cheered.”

The first public day, Saturday, August 1, was less propitious. Attendance was poor. At a venue regularly attracting 20,000, only 2,000 people turned up. Weather balloons zigzagging across the sky indicated wind gusts of 22 mph, which prevented any ascents. Instead, Farman had the Voisin paraded before the grandstands and explained its workings. After being warned to hold their hats, the crowd gasped as the Antoinette fired, generating “a terrific blast of air back towards the hundreds behind. Instantly a cloud of straw hats went hurtling into the air, high into the roof of the grandstand. The blast cleared a path like a cyclone. Fifty people were blown off their feet.”

(Canada Aviation & Space Museum/Corbis via Getty Images)

Entertaining perhaps, but not what the crowd had paid to see. They dispersed resentfully when Farman announced by megaphone in his thick French accent that flights would be postponed. Admitting “the spanking sea breezes that met the conservative foreigner,” the New York Times acidly described Farman as “walking through the clover to see if the wind was strong enough to justify his determination not to fly.”

Thereafter, things got worse. No demonstration had been planned for the next day, Sunday, August 2, so no officials were present. But despite the forecast of continuing gusts, conditions were sunny and calmer. While Farman tuned his Voisin in the makeshift hangar, 500 of Saturday’s disgruntled visitors huddled outside. MacMechan assured them that Saturday’s tickets would be valid for future flights, but the crowd responded with a chorus of threats and started forcing the gates.

When news of the fracas reached Farman, he acted swiftly. “I don’t blame them,” he said. “They paid to see me fly—many of them working people who can’t get here any other day. Let them in. Hurry!” To objections that there was no one to police the crowd, he replied “I have seen enough of the American people to satisfy me they don’t need police if you give them a fair show.”

Minutes later, the crowd surged through the gates, raced across the infield and surrounded the hangar so closely that it became impossible to roll out the Voisin. According to The Herald, “Farman, with his new-found confidence in American fairness, ordered the canvas doors to be drawn back, climbed on the machine and shouted at the crowd to stand back as the aeroplane was rolled out.”

An announcer asked people to be patient, and most obeyed. The wind died down to a westerly breeze. “There came a clattering sound from the aeroplane, and a cloud of dust could be seen leaping into the air,” reported the Herald. “The propeller flashed faster and faster, then the great machine darted forward, rolling rapidly over the ground. 200 feet from the start, it leaped into the air, rose 25 feet and came whirring over the field with the speed of an express train. At the end of the flight the motor was stopped, the slant downward begun, the motor started again for a few revolutions to lessen the shock of landing, the machine rolled along for about 100 feet. For a second or two the crowd was silent before the throng in the grandstand stood and cheered, but it was all over in less than a minute. Then the crowd dashed across the field to tell Farman that he was not a fake after all, but the real thing. Farman took it all coolly and begged the men not to hurt the machine: ‘Aeroplanes are babies yet—in the crawling stage—and you must be patient with them.’ Many of the men who were yelling themselves into a state of perspiration over Farman’s achievement were only five minutes before denouncing him as a fraud and exciting the more unruly elements to demand their money back or ‘have fun’ with his machine….”

(Courtesy Reg Winstone)

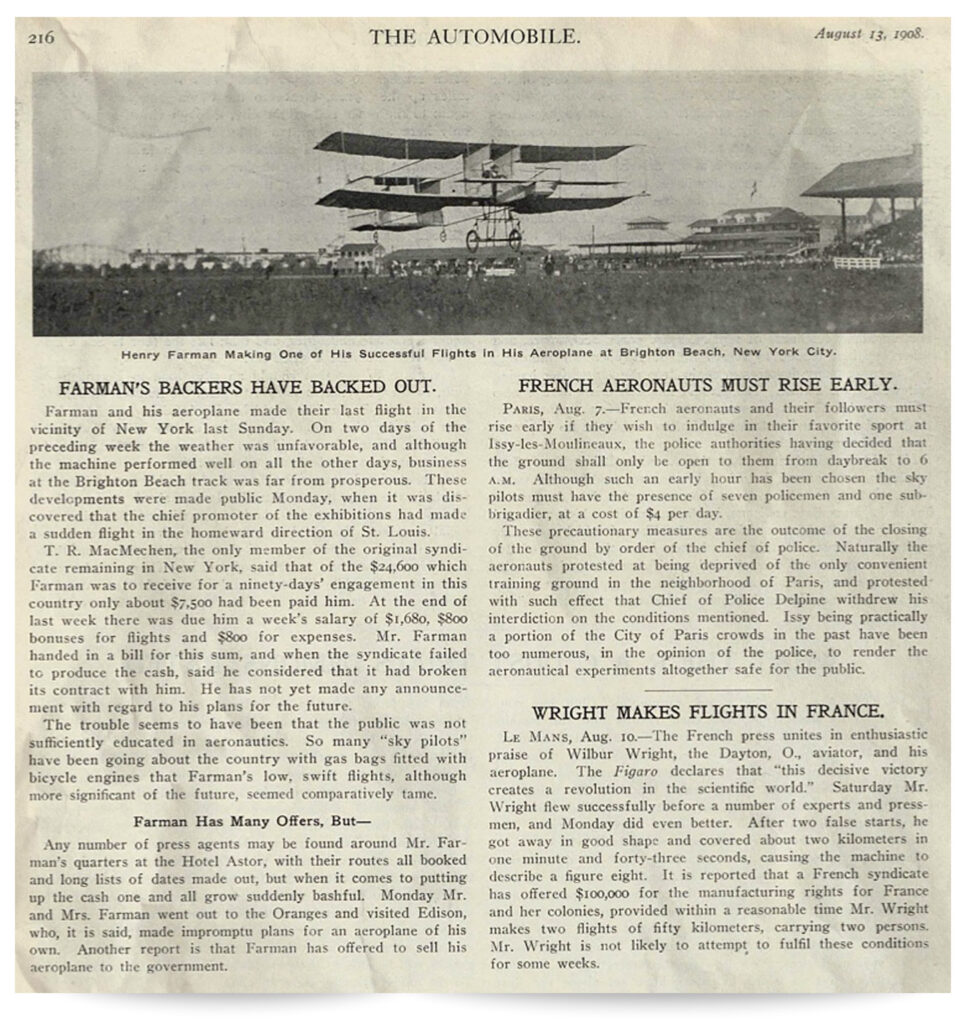

The Voisin had made a public flight, but it appeared that the tour was doomed by the combination of inadequate spectacle, misleading advertising, poor organization and increasingly critical press. Farman offered to sell his Voisin for $6,000, even suggesting that the government might buy it for the Fort Myer trials. The popular Vanderbilt Cup race driver Joe Tracy made an offer, which Farman turned down.

Matters didn’t improve. On August 5 Curtiss wrote, “Farman’s attempts were very disappointing. The first day he flew 140 yards at an elevation of three feet in 11 seconds, at about 20 mph. He made two such flights and then wheeled the machine back to the tent. Next day there were about 3,000 attending and as it was too windy, he did not attempt to fly.” On August 6 and 7, storms precluded further flights, with only three hops over the weekend; attendance by then was down to a few hundred, who showed more interest in the amateur motorcycle races organized at the last minute as an added attraction.

Ironically, in France Wilbur Wright was triumphantly demonstrating the superiority of his machine to incredulous audiences at another racetrack, near Le Mans. As far as transatlantic rivalry was concerned, it was game over. By contrast, Farman’s backers fled back to St. Louis and the contractor who erected the hangar attached the Voisin for a debt of $120. Farman sent him $50. Warned that other creditors would soon follow, he hired a fast car, some wagons and a local work crew. By the early hours of August 14, the Voisin had been hastily repacked and hustled off to the Manhattan Custom House and loaded aboard a Cherbourg-bound freighter.

With his machine safe, Farman accepted Thomas Edison’s invitation for a quick visit to the “play shop” at the great man’s New Jersey laboratory. There, he saw the Voisin flicker jerkily onto a screen in a short film that was advertised for public screenings in that month’s Variety.

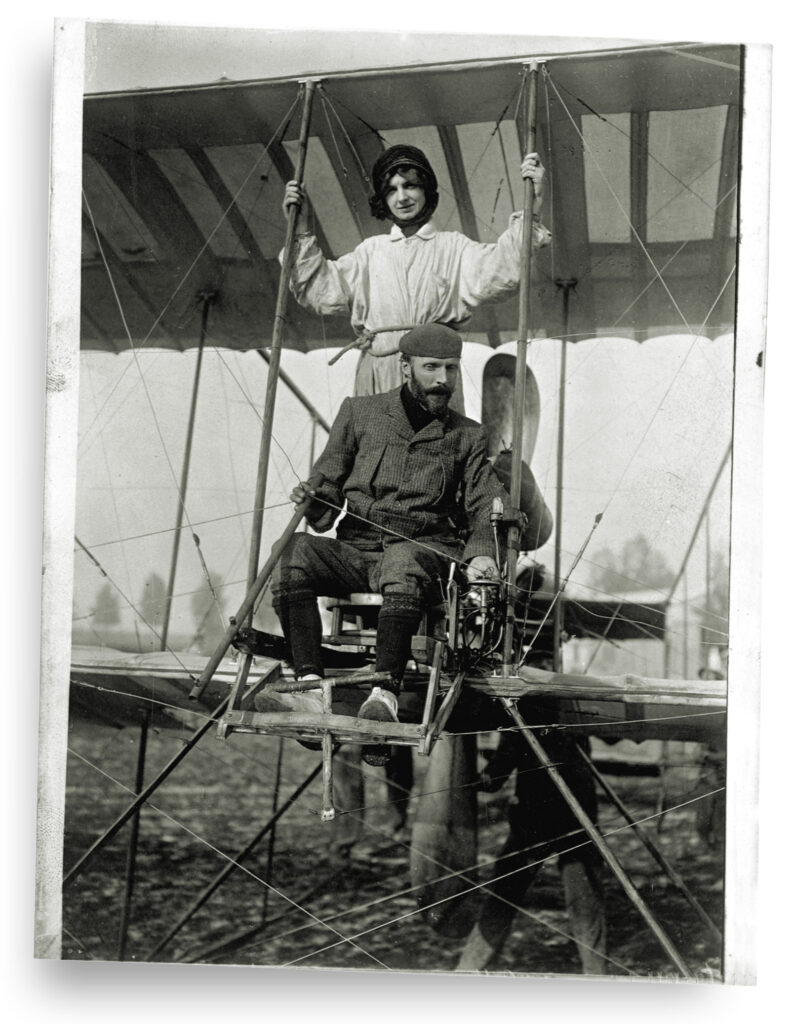

Stardom notwithstanding, Farman had only received a fraction of his promised fees. His wife was unimpressed by the visit to America. To the New York Sun, she compared audience expectations on both sides of the Atlantic. “The people here are not ready for such an advanced idea,” she said. “They would rather witness a race between two donkeys than see Farman fly. The machine is too technical for them to grasp and Farman flew so easily that they thought it didn’t mean much. He would have drawn more crowds if he had made several ineffectual attempts to sail and broken the machine a little—enough to give an idea that it was dangerous. In France it is different. Over there, where flights have been public and no one has to pay, I’ve seen 30,000 present at a flight.” The editor agreed: “Farman’s work seems almost too businesslike. At least he might make the machine wobble a little and dip dangerously to remind us that he really is flying and not running an automobile on some invisible aerial road.”

(Courtesy Reg Winstone)

For Aeronautics, the problem was the venue. “If the grounds had been large enough to allow long circular flights, people would have been anxious to see the flights, but with a straight flight of only a few hundred feet, people thought they had not seen enough for their money. Any flight is wonderful but the public wants a spectacle. Mr Farman fulfilled his side of the agreement as far as the ground permitted and must be of the opinion that interest in aeronautics on this side of the pond is really less than he anticipated.”

The New York Times riposted: “Mr. Farman is a bit ‘difficult’ and overconfident of his ability to steer his way among strangers.” The editorial concluded that it was a case of caveat aviator: “Mr. Farman did not exercise caution in the selection of his managers. Inventors are notoriously incompetent in business matters, and it is not only in the United States that their bright hopes of fortune fail to materialize.”

Farman remained pragmatic. “I said to myself before I came to America that I was not sure that the people were ready for such an exhibition of mechanical flight in the restricted area that seems a necessary adjunct to charging admission. If for no other reason than that the newspapers here have treated me with such kindness, I am glad the trip was made.”

Disillusioned, the Farmans headed back to France on August 15. Farman’s Brighton Beach flights were commemorated 30 years later by the painter Alois Fabry as part of a huge mural project inside Brooklyn Borough Hall done for the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration. Entitled “Brooklyn Past and Present,” the work immediately attracted controversy—for its style and because some people thought it included a depiction of Vladimir Lenin. Dedicated in 1939, the murals were removed in 1946 and have since disappeared.

Source link