[ad_1]

Odds are there isn’t a Civil War buff living who hasn’t seen a copy of this remarkable pencil sketch (above) by special artist Edwin Forbes, which Forbes labeled as “William J. Jackson, Sergt. Maj. 12th N.Y. Vol.—Sketched at Stoneman’s Switch, near Fredricksburg [sic], Va. Jan. 27th, 1863.” The young noncom has gazed back at us across the years from countless publications and exhibits. Rendered with camera-like honesty, it is arguably among the best drawings of a common soldier done during the Civil War. Writing about his work in general, Forbes assured viewers, “fidelity to fact is… the first thing to be aimed at.”

In fact, once Forbes completed his drawing of Jackson, the sketch went virtually unseen for more than 80 years. The drawing was among several hundred illustrations Forbes made while covering the Army of the Potomac for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper from the spring of 1862 to the fall of 1864. Approximately 150 of Forbes’ wartime sketches were engraved and printed in the illustrated newspaper during that period, although his drawing of Jackson was not among them.

(Library of Congress)

After the war, Forbes retained most of his original illustrations. Many he reworked into more polished drawings; some into oil paintings. He fashioned scores of them into award-winning etchings. Many appeared in his books, Life Studies of the Great Army (1876) and Thirty Years After: An Artist’s Story of the Great War (1890). Again, the poignant sketch of the beardless sergeant major from the 12th New York Infantry was not included.

Following Forbes’ death in March 1895, his wife, Ida, maintained his portfolio of original artwork, where the Jackson sketch was catalogued, “Study of an Infantry Soldier — The Sergeant Major.” She eventually sold the entire collection for $25,000 to financier J.P. Morgan in January 1901. Eighteen years later, on the heels of World War I, Morgan’s estate donated the collection to the Library of Congress, its current home. The sketch of William Jackson remained out of the public eye for another quarter-century until it resurfaced during World War II, thanks to the efforts of a U.S. Army private.

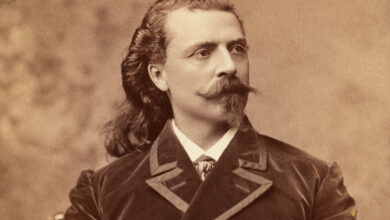

Private Lincoln Kirstein, however, was not your ordinary ground-pounder. Born into wealth, the Harvard educated Kirstein was well-connected socially, channeling his “energy, intellect, and organizational skills to serve the art world.” By age 36, when he was inducted into the Army in early 1943, Kirstein had already published several books, co-founded The Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, and later, The School of American Ballet in New York City with renown Russian choreographer George Balanchine.

Following his basic training at Fort Dix, N.J., Kirstein was posted at Fort Belvoir, Va., charged with writing training manuals. “I am an old man,” he confided to a friend, “and find the going very hard.” To fill his idle hours, he conceived an idea to collect and document American solider-art. “[M]uch of their work is interesting,” Kirstein wrote, “and some of it is beautiful.” He soon expanded his survey to include “U.S. battle art through time.” His plans included a “large-scale exhibit and a book.”

Aided by some influential friends, including Pulitzer Prize–winning poet and then Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish, Kirstein gathered material from various sources, including the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and, of course, the Library of Congress. Thanks to his efforts, Forbes’ sketch of “Sergt. Maj. William J. Jackson” emerged from obscurity.

The efforts culminated in the exhibition of American Battle Art at the Library of Congress staged from July 4 through November 1, 1944. Three years later, the Library of Congress issued the book that Kirstein had envisioned. Titled An Album of American Battle Art, 1755-1918, the heavily illustrated volume “took its origin” largely from the wartime exhibit. Forbes’ portrait of William J. Jackson appeared in print for the first time, captioned “a solemn lad with his arm resting on his rifle…toughened by campaigning.”

A Perilous Start

Jackson may have been “toughened” early in life. The son of Irish immigrants, he was born in New York City’s Greenwich Village on June 8, 1841, the first of four boys. His father, also named William, worked as a mason. The family grew in time, and moved from tenement to tenement, though always remained in proximity to Washington Square. The surrounding web of narrow streets flanked by a tumble of brick and framed dwellings and small businesses was an Irish enclave in the city’s 9th Ward facing the Hudson River.

It was a tough neighborhood. “Boys were primitive in those days,” wrote one of Jackson’s contemporaries. “They were like the old time warring clans. Every avenue was arrayed against the other.” Tensions bubbled within the city’s growing Irish immigrant population where clashes were common.

One notorious encounter erupted within a stone’s throw of Jackson’s home when he was 12. On July 4, 1853, streets echoed “the popping, fizzing, whirring and banging sounds” of fireworks as crowds of green-clad Irish revelers celebrated Independence Day. They ended up battling one another. “At one time several hundred men were…hurling stones and other missiles…” trumpeted The New York Herald next day. Platoons of policemen from nearby precincts aided by two fire companies “succeeded in subduing the riot…” Nearly 40 Irishmen were arrested, reported the Herald, “all of whom bore the strong evidences of an impression made on their heads by a contact against the policemen’s clubs.”

Battles of another kind rocked William’s world when civil war erupted on April 12, 1861. The 19-year-old left his parents and his job as a clerk a week later, on April 19, to enlist in the 12th Regiment New York State Militia, Company F. A recruiting office was just blocks from his home.

Tendered for immediate service by its commander, Colonel Daniel Butterfield, the regiment also included in its ranks the future Maj. Gen. Francis C. Barlow when it sailed from New York on April 21, bound for Washington, D.C. Though fully armed, the unit lacked enough uniforms to go around. Raw recruits like Jackson wore “their ordinary clothing with military belts and equipment,” giving them, by one account, a “guerrilla like,” appearance. Appearances changed when a new Chasseur uniform was issued to the regiment at Camp Anderson in Washington early in May 1861. The militiamen were also mustered into Federal service for three months while there, and received a “severe course of drilling.” Barlow was mustered in as a first lieutenant in Company F.

One of their Camp Anderson instructors also distinguished himself later in the war. Emory Upton, fresh from graduation at West Point, would achieve the rank of Brevet Maj. Gen., and eventually become superintendent of U.S. Military Academy. Upton found that tutoring the 12th New Yorkers was tiresome. “I do not complain,” he wrote, “when I think how much harder the poor privates have to work.”

(Library of Congress)

Their crash course in soldiering quickly paid off. Before dawn May 24, the 12th New York led Union forces over Long Bridge to occupy Alexandria, Va., and fortify Arlington Heights in the wake of that state’s secession from the Union the day before. Jackson was among the first Union infantrymen to set foot on Rebel soil.

Jackson continued his trek through enemy country when the regiment joined Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson’s army at Martinsburg, Va., on July 7, 1861. The men patrolled and picketed environs of the Lower Shenandoah Valley until their expiration of service on August 2, when the unit returned to New York. Following a march down Broadway and Fifth Avenues on Monday August 5, the regiment formally mustered out at Washington Square, near Jackson’s home.

Quick Return to the Fray

Jackson’s homecoming was brief. He reenlisted October 1, 1861, and mustered into Federal service for three years, a member of Co. F, 12th New York Volunteer Infantry. Dubbed the “Onondaga” Regiment, its ranks had originally been filled with short term volunteers from near Syracuse and Elmira, N.Y., in May 1861. After the Union debacle at First Bull Run in July 1861, the regiment recruited around the state including in New York City where Jackson signed on. Perhaps showing potential from his recent militia service, William was immediately appointed sergeant.

Recruits ferried over the Hudson River from Manhattan to Jersey City, N.J., and boarded trains for the trip south to join the regiment then on duty in defenses outside Washington, D.C. Recalled another New York volunteer who made the trip about the time Jackson did, “the cars were crowded and the ride was slow, cold and tedious.”

From Washington, the novice soldiers crossed Chain Bridge over the Potomac River into Virginia. Union Army engineers had fortified the landscape to defend the Capital. “Every mile is a fort,” marveled Private Van Rensselaer Evringham, Co. I, 12th New York. “There is thousands of acres here that have been cut down & left on the ground to prevent the Rebels coming by surprise…it would take 50 years to bring everything back to its former state.”

The 12th New York, given the moniker “the durty dozen,” according to Evringham, joined scores of other raw regiments manning fortifications throughout the fall and winter 1861–62, while they trained for combat ahead. Jackson’s Co. F, with four other companies from the 12th garrisoned Fort Ramsay, located on the crest of Upton’s Hill, about a half mile east of Falls Church, Va. They also furnished a daily guard “to protect the guns in Fort Buffalo” nearby. The regiment’s remaining companies manned Fort Craig, and Fort Tillinghast. They occasionally traded shots with Rebel forces, “but to little effect,” wrote a New York diarist.

On March 21, 1862, Jackson and tent-mates were ordered off Upton’s Hill to Alexandria, Va. Next morning, boarding the transport John A. Warner to the strains of Dixie, they steamed down the Potomac River to Chesapeake Bay. In a letter to his parents, Private Homer Case, of Co. I, confided: “We did not know where we was a going.”

After two days aboard ship, Jackson and “the durty dozen” landed at Hampton, Va., embarked on Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s offensive to take the Confederate capital at Richmond. Hard marching through steaming pine thickets and swampy bottom lands on narrow, crowded, often rain-mired roads marked the campaign. Private Sid Anderson, Co. H, quipped of “mud clear up to the seat of our unmentionables.” While Private Evringham claimed, “Virginnie is 2/3 woods or swamps.”

Under Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter’s command during the fruitless Union thrust up the Peninsula, the 12th New York saw action at the Siege of Yorktown, the battles of Gaines’s Mill and Malvern Hill, and numerous skirmishes in between. Afterward, the New Yorkers languished at Harrison’s Landing until mid-August when they trudged to Newport News. From here they traveled by steamer to Aquia Creek; then by railroad to Falmouth, and on by foot to join Maj. Gen. John Pope’s ill-fated Army of Virginia near Manassas, Va. “We marched thirteen days…with little rest,” wrote Private Robert Tilney, Co. F., “part of the time on half rations…”

At the Second Battle of Bull Run, the Onondagans engaged in bloody afternoon assaults on August 30, against Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s position astride the railroad cut. “We poured volley after volley into the concealed enemy,” recalled one New Yorker. Rebel return fire shredded the Union foot soldiers, “woefully thinning” their ranks. Nearly a third of the 12th New York became casualties.

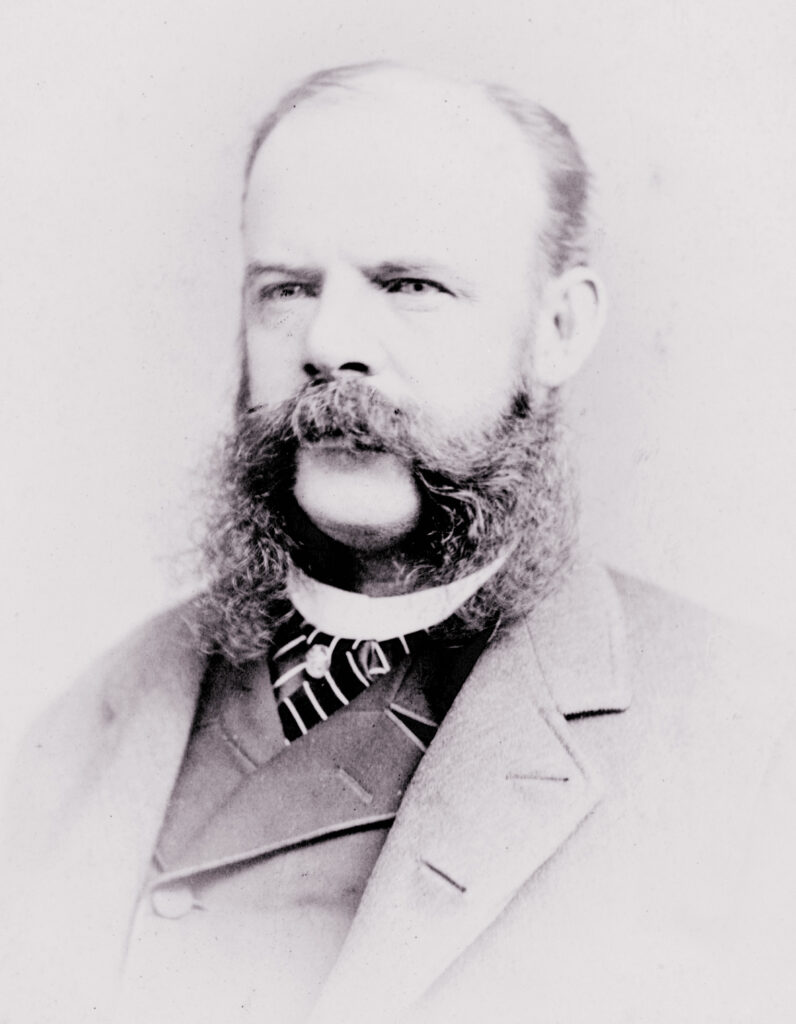

Facing Lee’s army at Sharpsburg on September 17, Sergeant Jackson likely had mixed emotions while he and his regiment stood in reserve with Porter’s 5th Corps, mere spectators to the bloody Battle of Antietam. The Sharpsburg area remained Jackson’s home through the end of October 1862, when the regiment advanced via Snicker’s Gap and Warrenton, to the Rappahannock River where the Army of the Potomac arrayed opposite Fredericksburg. The boyish-looking sergeant would earn three more stripes during the ensuing battle.

(Library of Congress)

Jackson’s regiment with Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin’s division occupied Stafford Heights when the Battle of Fredericksburg opened on December 13. They crossed the lower pontoon bridge in early afternoon, struggling through debris in Fredericksburg amid what one New Yorker described as “a shower of aimless bullets.” The regiment advanced to a shallow fold in the ground about 500 yards from Rebels posted at the stone wall on Marye’s Heights. “[T]his position,” reported brigade commander Colonel T.B.D. Stockton, “was much exposed to the cross-fire of the enemy’s guns…”

Stockton’s Brigade charged the stone wall just before sundown. The 12th New York missed the bugle signal to advance in the din of battle, though soon recovered, sweeping forward. They met a maelstrom of shot and shell “on both front and side,” wrote Stockton. The New Yorkers piled into the tangled mass of bluecoats already stalled at the foot of Marye’s Heights and went no farther. Ordered to hold their exposed position under enemy fire throughout the night Stockton’s men were bait for Rebel sharpshooters and artillery until relieved about 10 p.m. December 14. It was “all a person’s life is worth to go to or come from there,” wrote a newspaperman. Young Jackson suffered a gunshot wound to his left leg below the knee that day.

When Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside ordered his battered army back to its old camps north of the Rappahannock on December 16, Jackson returned as a sergeant major. He had been promoted the day before, likely to fill a vacancy caused by the battle.

Jackson saw little combat after the Battle of Fredericksburg. The 5th Corps wintered in a small metropolis of timber and canvas huts near Stoneman’s Switch, a supply depot along the railroad several miles north of Fredericksburg, where the 12th New York engaged in an “uneventful round of camp and picket duty.” It’s uncertain whether Jackson’s injured leg kept him from chores, or prevented him from joining Burnside’s inglorious “Mud March” in pitiless wind and rain storms January 20–24.

(Library of Congress)

By January 27, however, the 21-year-old Jackson, with bayonetted rifle, his greatcoat tightly gathered at the waist, was able to stand still long enough for special artist Edwin Forbes to capture him on paper. The artist clearly shows that Jackson placed his weight on his right foot. No evidence has surfaced to indicate Jackson and Forbes knew each other, or ever met again after the drawing was completed, though Forbes remained in the area depicting numerous scenes around the Stoneman’s Switch camps that winter.

In late April 1863, the 12th New York was reduced to battalion-size when five “two-year companies” were mustered out of the army. Jackson and the remaining companies with the 5th Corps followed Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker to Chancellorsville, Va., in early May. During the battle there, the New Yorkers were employed “making rifle-pits and abatis” on the fringe of the fighting. “[I]n this position,” recalled a private in Company D, “we saw the fires in the woods which the artillery had kindled, and heard the cries of the wounded.”

Expiration of service further reduced ranks of the regiment after the Battle of Chancellorsville. Jackson and other “three-year” men were then consolidated in a two-company provost guard. The contingent moved with 5th Corps headquarters when the Army of the Potomac pursued Lee’s Rebels toward Pennsylvania. “Our troops had been on the march for many days,” wrote the Company D soldier, “bivouacking at night in the open air, and were dirty and travel-stained with the heat and sun of late June.” This ordeal ended abruptly for Jackson on June 30. On the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg, at a camp near Frederick, Md., Sgt. Maj. Jackson was granted an early discharge from the army “by reason of being rendered supernumerary…” (surplus due to the consolidation).

Battle With Postwar Bureaucracy

Jackson returned to New York City and married in 1865. Employed as a clerk/salesman, he and his wife, Maria, set up housekeeping in Brooklyn. Over time, they were blessed with three daughters. Elizabeth, their first child, born in 1866, suffered from an unspecified disability and likely remained homebound until her death in April 1891. Margaret, born in 1869, worked as a file clerk, remained single, and passed away in 1920. Ellen, or Nelly, Jackson, who was born in 1871, was also employed as a clerk, and unmarried. She lived well into the 20th Century, passing away in October 1945.

Outside his family and job, William Jackson had enrolled in the Old Guard Association of the Twelfth Regiment N.G.S.N.Y., and in “The Lafayette Fusileers,” antecedents of the units he served with during the war. The rigors of his army service eventually took a toll on Jackson’s health later in life.

At age 51, Jackson filed his first claim for an Invalid Pension in June 1892. The former sergeant major supplied a laundry list of disabilities on his application form: “[A]lmost constant superficial pain in right chest & some in legs…pain & violent beating in heart…weakness – can’t lift anything.” His “gunshot wound of left leg” was cited. In sum he was “Physically unable to earn a support by manual labor.” Military medical records also show Jackson had been treated for “Gonorrhoia” [sic] on November 13, 1861. (Perhaps the result from a visit to one of the hundreds of brothels around Washington, D.C., while his regiment was on garrisoned duty.)

Jackson’s claim was rejected, “on the ground of no pensionable disability…under Act of June 27, 1890.” It wasn’t until President Theodore Roosevelt had signed an Executive Order for Old Age Pensions declaring all veterans over the age of 62 to be eligible for a pension that Jackson was finally granted $6 per month beginning May 10, 1904.

The reward would be short-lived. On April 11, 1905, following Maria’s death that January, William J. Jackson died. He and his wife rest with their three daughters under a single headstone at Cedar Grove Cemetery in Flushing, N.Y.

George Skoch, a longtime contributor, writes from Fairview Park, Ohio.

Source link