[ad_1]

In 2003, the historic Thessaloniki Summit marked a pivotal moment for Europe and its enduring commitment to enlargement and unity. At the heart of this gathering in the timeless Greek city was the visionary idea to bring the Western Balkans into the European family. The summit not only reaffirmed the EU’s dedication to the enlargement process but also set into motion the integration pathways for countries emerging from a tumultuous past. This was a gesture of hope, signifying that shared values and collaborative efforts could overcome even the most deep-seated challenges. However, two decades after the hopeful summit, the aspirations of the Western Balkans and their integration into the European Union remain, in many ways, unfulfilled.

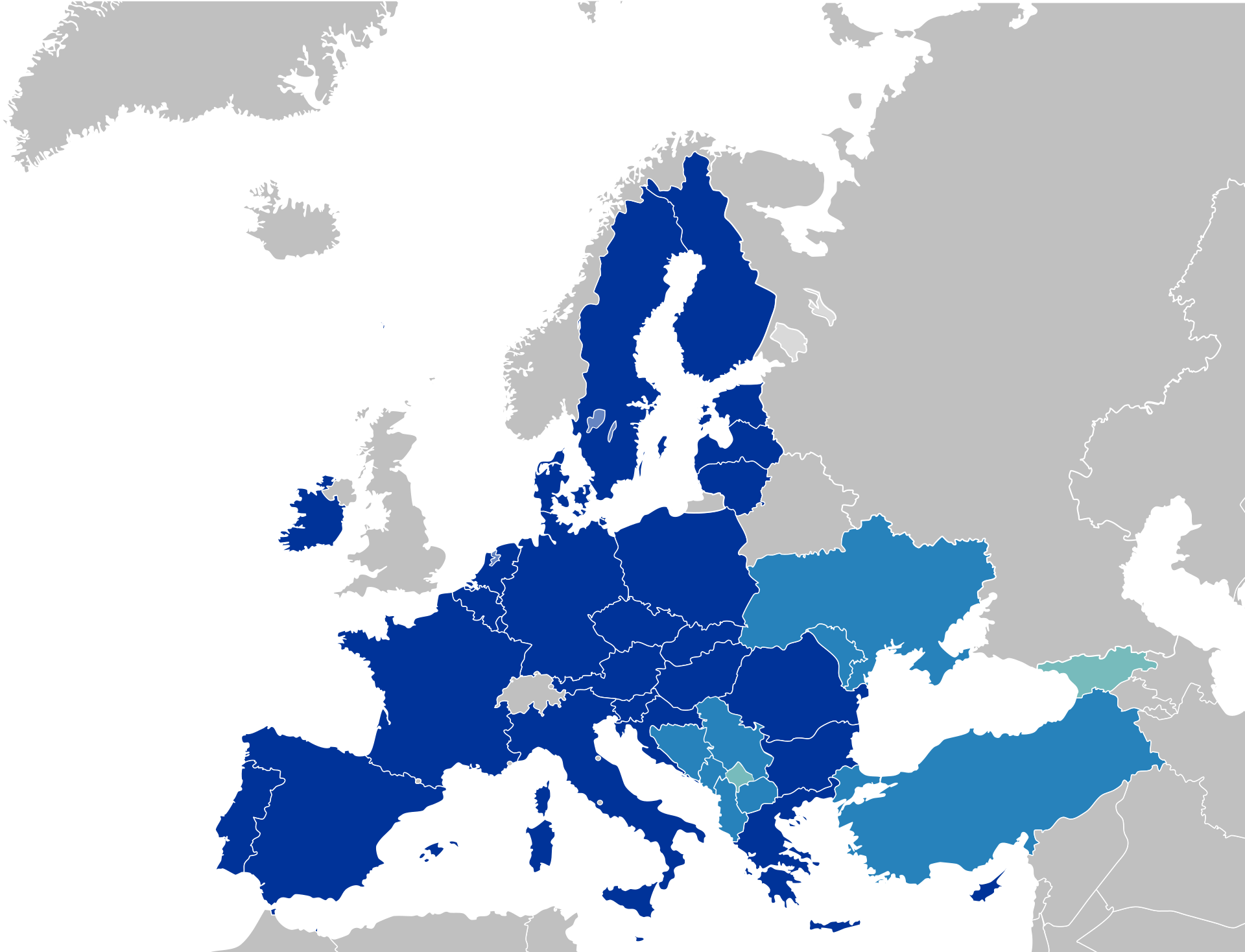

Croatia is the only country to have achieved EU membership in 2013. Meanwhile, Serbia and Montenegro embarked on their accession negotiations processes only in 2012. On the contrary, Albania and North Macedonia still await the formal start of accession negotiations, which were greenlit by the European Council in March 2020. Bosnia and Kosovo, while recognised as potential candidates, are still in the preliminary phases. Kosovo’s path is nuanced due to its non-recognition as an independent state by several EU members.

Current members, candidates, and potential members of the EU. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

State of limbo

The overarching theme in the region’s EU aspirations is that while significant strides have been made, there is little to no reason to commemorate the 2003 Thessaloniki Summit and its accomplishments regarding the expansion of the EU project in the Western Balkans. While the summit had promised a brighter, unified future, a combination of regional complexities, unresolved historical disputes, and internal EU dynamics have stalled the process.

This continued state of limbo has raised questions about the EU’s commitment and the feasibility of its enlargement strategy. The EU has long presented itself as a symbol of unity, cooperation and progress. A project that commenced in the post-war era to ensure peace and economic cooperation in Europe, the EU has since expanded its boundaries, integrating many Central and Eastern European countries. The fact that the Western Balkans countries remain largely outside of the EU raises serious questions about the EU’s ability to expand and secure European values in its own neighbourhood, let alone play a global role for the stability of the liberal order in the world.

What are the reasons for this delay? It depends on who you ask. Overall, the initial momentum has been overshadowed by reluctance within the EU, geopolitical complications, and pressing bilateral issues among the aspiring members. In other words, the stagnation of EU enlargement in the region can be attributed to many different factors.

Historical tensions and unresolved issues – The 1990s saw the dissolution of Yugoslavia, leading to a series of violent wars and deep-seated ethnic and religious tensions in the Western Balkans. These tensions persist today. The political borders that emerged post-conflict often do not align with ethnic boundaries, leading to internal disputes and tensions. For instance, the Bosnia and Herzegovina constitution, which divides power among three main ethnic groups, is often criticised for its inefficiency and for perpetuating ethnic divisions.

Rule of law and corruption – One of the major criteria for EU accession is the establishment of the rule of law. The Western Balkan countries often rank low in global corruption indexes. Issues ranging from judicial corruption to political bribery persist, making it difficult for these nations to meet the stringent demands set by the EU.

Economic disparities – Stability and growth are essential prerequisites for EU membership. However, many Western Balkan nations face economic issues, including high unemployment rates, underdeveloped infrastructure and a lack of foreign investment. Aligning these economies with the more prosperous EU nations remains a challenging task.

EU enlargement fatigue – Over the past few decades, the EU has integrated many countries, especially from Eastern Europe. This rapid enlargement has led to ‘enlargement fatigue’, with some member states becoming wary of further expansion, fearing that it might dilute the EU’s core values or strain its resources. Similarly, in the context of migration and economic concerns, in some EU countries public opinion on further expansion is mixed or negative. This sentiment can influence the decisions of political leaders when it comes to accepting new member states.

Veto power and bilateral disputes – Certain EU countries have unresolved issues with Western Balkan states. For instance, Spain is hesitant about recognising Kosovo due to its own secessionist movements. Similarly, Greece had disputes with North Macedonia over its name for years, which were resolved only recently. A dispute with Bulgaria is now obstructing the same country from starting accession negotiations.

Geopolitical factors – Russia and China have significant interests in the Western Balkans. Their influence, through investments and political alliances, often competes with the EU’s efforts in the region. This geopolitical game has slowed down the EU integration process.

Thus, the integration of the Western Balkans into the EU is not merely a question of political will. It is a complex puzzle that involves historical baggage, socio-economic disparities and geopolitical considerations. Nevertheless, while the known causes such as enlargement fatigue, internal EU challenges, geopolitical influences and concerns over candidate countries’ readiness undeniably play a role in the stagnation of EU enlargement, it is worth noting that similar issues have been encountered and navigated in past expansions. The EU has historically demonstrated an ability to handle complex integration scenarios. This should lead us to suspect that there may be an underlying, less-discussed reason contributing to the delay. This hidden cause, yet to be fully addressed, could be the missing piece of the puzzle that explains the protracted integration process for certain Western Balkan nations – a missing piece that could also show us the way forward.

A matter of public administration

Beyond its evident geopolitical, economic and symbolic significance, the EU integration process is, at its core, an administrative endeavour of immense proportions. The journey to EU membership requires a candidate country to undertake vast and comprehensive reforms within its public administration. This is not merely about alignment with the EU’s political or economic objectives; it is about ensuring that the administrative machinery of a nation is robust, transparent and efficient enough to conform to the EU acquis – the accumulated body of EU law and regulations. This necessitates an intricate intertwining of policies, legal frameworks and institutional practices, making the integration process as much about bureaucratic transformation as it is about political or economic alignment.

An effective public administration stands as the linchpin in this bureaucratic process of EU integration. Why? Because integrating with the EU is not merely about meeting broad benchmarks; it is about the meticulous implementation of thousands of specific regulations, standards and directives that comprise the EU acquis. To navigate this complex roadmap, a nation requires an administrative apparatus that is not only knowledgeable and competent but also transparent, accountable and adaptable. Efficient bureaucracies ensure that laws and regulations are applied consistently and fairly, promoting trust both domestically and with EU counterparts. Furthermore, as the EU’s policies span diverse areas – from environmental standards to consumer protection – a country’s administrative bodies must work cohesively across sectors, ensuring that no detail is overlooked. Without a robust and effective public administration, the foundational structure required to support and sustain the demands of EU membership would simply collapse, making it an indispensable asset in the integration journey.

The path to the EU, commonly perceived through the lens of political will, constitutional reforms and geopolitical nuances, dives much deeper into the granular, yet monumental, task of building administrative capacity. While high-level political decisions and geopolitical alignments are undeniably essential components, the actual execution of integration mandates lies in the hands of public servants and the machinery of bureaucracy. It is one thing for leaders to agree on policy directions and reforms, but it is another for a country’s administrative apparatus to translate those agreements into actionable steps, compliant with the vast expanse of the EU acquis.

Without a capable and competent cadre of public servants, the most well-intentioned political commitments can falter in execution. The process requires a deep understanding of EU directives, the ability to draft compliant legislation and the expertise to oversee its implementation across various sectors. This capacity-building is not just about numbers or staffing; it is about training, knowledge transfer, inter-departmental coordination and fostering a culture of transparency, efficiency and accountability.

In essence, while political will, constitutional reforms and geopolitical contexts set the direction for EU integration, it is the capacity of public administration that drives the journey. Delays in integration are as much a reflection of administrative capacity challenges as they are of high-level political or geopolitical impediments.

Clock tower and flags in Albania, taken by Marcin Konsek via Wikimedia Commons.

The real reason behind the delay

Emerging from the devastating wars of the 1990s, the Western Balkan countries found themselves grappling with the remnants of conflict and the challenges of building anew. One of the primary legacies from this tumultuous period, and from the times of the former Yugoslavia, was a public administration system that was predominantly influenced by Serbian bureaucratic traditions. While this system was adapted to the centralised governance of Yugoslavia, it was not primed for the comprehensive and nuanced demands of the EU integration process. Several factors come into play when understanding these administrative shortcomings.

First, the region’s reliance on a centralised, Serbian-dominated bureaucracy meant there was limited experience and expertise in managing diverse, decentralised administrative structures. In addition, the war left behind deep-seated mistrust among communities. Building an inclusive public administration system that catered to the diverse ethnic, religious and cultural groups in the region became a challenge. Second, the post-war rebuilding meant that many countries in the region were primarily focused on immediate recovery, reconstruction and reconciliation. Building an administrative system aligned with EU standards was not the immediate priority and thus it lagged behind other recovery efforts. Moreover, funds that could have been allocated to administrative reform were often redirected to more pressing immediate needs.

Third, the capacity and expertise in public administration was affected by the war. Many professionals either left the region, were involved in the conflict, or were part of a system that was not oriented towards EU administrative norms. This created a dearth of skilled personnel familiar with the rigorous demands of EU standards. The task of transforming public administration in the Western Balkans is monumental. It requires not only structural changes but also a shift in mindset, ethos and values to align with EU principles and standards. And while there is awareness within the EU about these challenges, the lack of efficient public administration capacity in the Western Balkans is not discussed enough as a reason for the delay of EU integration in the region.

What the EU can do

To expedite the Western Balkans path to integration, the EU must zero in on key strategies that not only bolster administrative capacities but also foster a deeper understanding of EU processes:

Targeted training programmes – Tailored training sessions specifically designed for Western Balkan public servants can bridge knowledge gaps and foster proficiency in EU law, policy formulation and integration requirements. By immersing these officials in specialised curricula, the EU can ensure that they are adequately equipped to navigate the intricate maze of accession demands.

Twinning projects – These collaborative endeavours between EU member state institutions and their counterparts in candidate countries can be game-changers. Through direct partnerships, Western Balkan administrations can glean insights, learn best practice, and draw lessons from those who have successfully tread the integration path. This hands-on approach is invaluable, creating real-world synergies and promoting mutual learning.

Encourage exchange programmes – Allowing public servants from the Western Balkans to spend time within EU institutions can provide an immersive learning experience. Being directly exposed to the functioning of EU bureaucracies, they can gather practical knowledge, build networks and understand the nuances of EU administrative processes. This experiential learning can be transformative, equipping them to replicate effective practices back home.

By focusing on these strategies, the EU can play a pivotal role in surmounting administrative challenges, thereby streamlining the Western Balkans’ journey towards EU membership.

Staged integration approach

A streamlined, efficient and responsive public administration is the backbone of any nation’s governance system. For countries aspiring to join the EU, this becomes even more significant. The integration process is not merely about political alignments or economic compatibility; it is an administrative exercise at its core. If EU enlargement is to be expedited, it is paramount that the public administrations of candidate countries be integrated first.

This argument lends credence to the idea of a ‘staged integration’ approach. Instead of expecting candidate countries to overhaul every aspect of their systems simultaneously, the EU should prioritise the integration of public administration. This means bringing administrative structures, processes and capabilities in line with EU standards before delving into deeper political or economic integrations.

The staged integration model posits that a strong administrative foundation will streamline subsequent stages of the accession process. Once the public administration is integrated, it can effectively manage, coordinate and implement the necessary reforms in other sectors, whether they are judiciary, economic or social policies. It is akin to building a sturdy base for a skyscraper; with a robust foundation, the subsequent construction becomes more feasible and resilient.

Furthermore, this approach can lead to more tangible, immediate results, thereby boosting the morale and confidence of both the candidate countries and their populations. When citizens see efficient administrative processes, transparency in governance and improved public services, they are more likely to support and trust the broader integration process.

Thus, for a swifter EU enlargement, integrating public administration should be the first order of business. A staged integration approach, anchored on this premise, could be the game-changer the enlargement process needs. As the world continues to evolve, it remains to be seen how the EU and the Western Balkans navigate their shared path toward unity and cooperation – and the very essence of what the European Union wants to represent in the future.

Source link