[ad_1]

Horror.

A word that I’ve been thinking about more and more. And the face of Colonel Kurtz who wasn’t real. He was a protagonist of a film, the embodiment of an idea, a symbol, energy, a phallus, a sign, pure evil, and thirst in hell. It suddenly occurs to me that I haven’t seen any trams in a while. It’s a strange thought, a phenomenological one. From the point of logic, it’s wrong, it doesn’t reflect actual reality because I see trams all the time. I walk past them every day downtown. Rather, I’ve stopped noticing them – they are also only a symbol, a bridge over the river of events that helps us understand that horror lingers around us. And, if you need to grab onto something, you’d better pick something large. Trams fit the bill. If you stop noticing them, you’d better believe you’ve hit rock bottom. They’re so strange: time after time, this red-and-white Soviet past trundles along, massive, iron, gray, monstrous, like an apparition, only a noisy one.

But it’s important to hold on to the thought that horror sneaks up imperceptibly, through a book for example. Books have always been a last refuge, that safe haven in a storm. Suddenly they’ve disappeared, too. Why read anyway? The authors haven’t seen horror, and the ones who have, have turned it into an altar. The colonel didn’t believe in it; he drank with it. A chalice face-to-face with the horror that became his friend, like those evening bonfires Nietzsche so loved. Nietzsche would allegedly clamber along the rocks at night and light fires. I can imagine him collecting kindling, the fire burning, being whipped up by the north wind. In time, the wind of history would bring concentration camps to Europe. ‘Earth’s great noon’ would eventually force humanity to take a look at itself through the light of World War I and later II: only naked existence with no social or cultural ‘shadows.’ But we were still far from the horror.

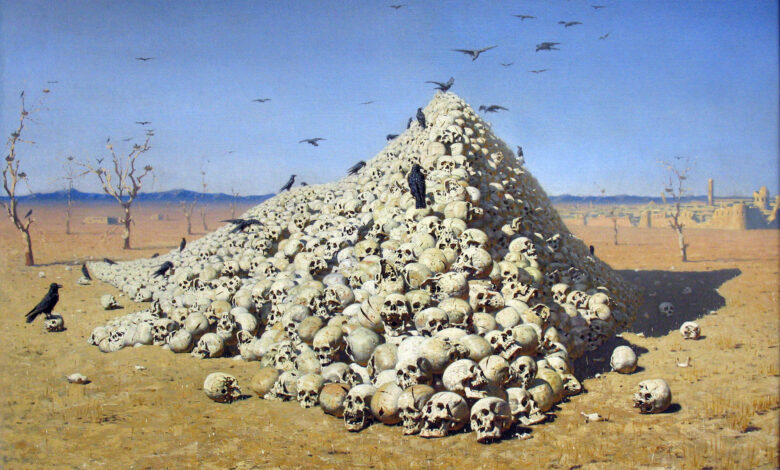

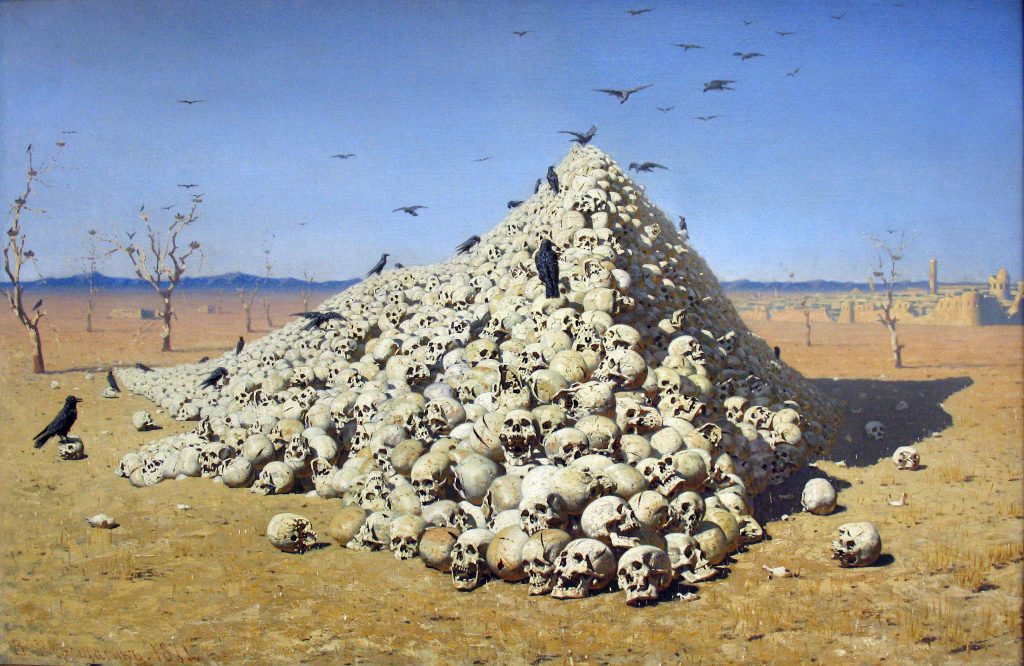

Vasily Vereshchagin, ‘The apotheosis of war’, 1871. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Every war encapsulates that which people would prefer to forget. In this sense, all wars are the same: since ancient times to the contemporary Russo-Ukrainian war, people have destroyed others like them with a particular cruelty that has come to be called ‘horror’. If you trace wars through ancient or medieval art, you’ll see severed heads impaled on pikes, captives skinned alive, the defeated with their limbs cut off, and so on. It is customary to believe that all that was a thing of the past, or at least peculiar to African countries, where local wars are still fought with demonstrative brutality toward one’s enemies.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shattered this shaky illusion. But the main point here is not only the mass murder and burial of civilians the Russian army carried out in the Kyiv and Kharkiv oblasts. After all, the Russian government officially refutes this, attempting through lies to save face in the so-called ‘rules of war’. The crux of the matter is Wagner. The private military company has become famous the world for its cruelty towards both the soldiers of the Ukrainian Armed Forces and its own mercenaries. What’s ‘unique’ about Wagner is that – unlike the Russian state – it doesn’t renounce its cruelty, but advertises it instead and turn it into a cult. This cult of horror not only ensures iron discipline within a structure made up of thousands of criminals convicted of particularly violent felonies, but also generates fear for the external consumer.

The Russian war in Ukraine has turned horror into a social phenomenon, yet another category of consciousness. Since ancient times, philosophy has viewed these categories as a way to approach the essence of things. Quality, Quantity, Place, Substance and Time have contained the world, remade and reflected it. Now the understanding of reality comes through existential horror: cutting off heads, filming it, collecting hundreds of likes and positive comments. A new demand for horror.

This brings us back to Apocalypse Now and its protagonist. Colonel Kurtz is the logic of war pushed to the limit. War is only a tool, an accident in a certain sense, one supposed to show the true evolution of humanity. And this evolution is by no means in iPhones. It has gone from the cross to the hammer used to drive in the nails. Love (Christ’s cross) has been supplanted by Horror – Wagner’s hammer. Dostoevsky’s ‘grand inquisitor’ of today isn’t a feeble old man in a cardinal’s red robe. He wears epaulettes with stars. He wouldn’t give a lengthy, impassioned monologue before Christ – more likely, he would just toss his bloodied hammer to his feet. I suspect in our time the ‘inquisitor’ wouldn’t say anything; his meeting with Christ would be silent.

This is a strange feeling of pure meaning, one that increasingly engulfs me. I often hear: why don’t you write, or write so rarely? There’s so much happening, just put it into words. But I have no words. They’re unnecessary. It seems everyone has already realized this: what could you possibly add to a head cut off or crushed in front of the whole world? Analyses, predictions, sympathy, even ire and curses are all incongruous. Everything is grotesque, a caricature of reality, except for the word ‘horror.’

But it is also empty, since it instantly crumbles into thousands of meanings: everyone imbues it with their own. Horror isn’t fear, which always has an object: death, heights, spiders. Horror is impossible to see in language, which is why only the existence of horror matters, the processes that happen in parallel, and the contrast – not the results or the shock. A tram noisily racing down the tracks carrying a dozen people on their morning errands while, at the same time, someone’s head is being pressed between a wall and a hammer. What were we doing when this was happening? Maybe buying groceries, putting eggs and ketchup into our carts, at the very moment that, in a stretch of forest in Donbas, a Ukrainian soldier’s head was being sawn off alive, the video ‘leaked’ to Telegram along with the screams.

I remember going to Bucha with my territorial defense unit. Our section hadn’t taken part in the fighting and we entered the city on the sixth day after the Russians had left. We already knew about the mass murder of civilians, and countless journalists from all over the world were standing around the church: bodies were being exhumed. We decided to drive down some side streets because a local guy said he’d seen a pile of burned bodies that way. Indeed, on Staroiablonska Street, which the whole world came to know, we came across the remains of the fire between some small cottages. We couldn’t tell for sure how many people lay there – I personally counted four. One of the bodies was ripped in half and a few meters away we found a burned leg that the hungry local dogs, abandoned by their owners when they evacuated, had chewed off. The Russians just piled up the bodies and set them on fire. If you stood just ten meters back, they looked like a pile of ordinary trash someone had burned in their yard. And, actually, that’s in part what it was: the charred bodies lay next to some construction detritus. The people who did this wanted to show, consciously or not, that human life meant no more to them than dirt.

But the horror on that day was hiding in the sun. It was a surprisingly sunny day for early April There was a small pine forest across the street and the yard itself was surrounded by large homes that until recently had been occupied by the local middle class. Presumably it was a portion of that class that was now being eaten by the dogs. It’s strange, but now, a year and a half since that day, I occasionally open a map of Staroiablonska Street on my computer and just look at it. I suspect that for me this is a stand-in for that April sun beating through those pines onto the burned bodies. You look at the straight line of the streets, the logic of the city, its ponds and trees, and can’t fully believe that it was at this spot on the map that you were overcome by nausea from the yellowed remains of corpses.

Now an obvious but important question: how to overcome the horror? Violence can always be met with violence, but responding to horror with horror creates something different: it doesn’t disappear, only drives people deeper into themselves. During one of Colonel Kurtz’s monologues in Apocalypse Now, the camera pans the books he has been reading deep in the jungle. One of them is Sir James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough, an allusion to the film’s final scene and all the suffering that Kurtz, who has experienced the horror of war and cultivated it around him in the form of the severed heads of locals, has gone through.

In the book, Frazer, a scholar of comparative religion, tells the tale of the rex Nemorensis, a priest of the goddess Diana. A dark figure keeps watch around a sacred tree from morning to deep in the night. He carries a sword and constantly glances around as if expecting an enemy to attack. This is the murderer priest and, sooner or later, the one he awaits will kill him and take his place. This was the law of that sacred place. The challenger for the priest’s place could gain the title only by killing his predecessor. The victor then held the position until a stronger challenger killed him.

At the end of the movie, Kurtz dies at the hand of an officer whom the army sends to assassinate him when his methods of war become ‘unacceptable’. At this, the locals bow down to the assassin who, in their eyes, has become the new priest. However, he rejects this status and leaves in his boat. Catharsis sets in: as the colonel is dying, he whispers, ‘The horror, the horror,’ and with that is finally freed of it. Neither his awareness (‘you must make a friend of horror’) nor his implementation of it in everyday life could free Kurtz from the horror he experienced in an Asian village, when he saw a mountain of children’s arms hacked off after they had been inoculated against polio. Only his physical murder frees him from it.

What about catharsis, anyway? In antiquity, this Greek word was mostly used in two senses: the expiation of guilt or physical alleviation of an illness. It’s interesting that, before he dies, Kurtz tells his murderer, ‘You have a right to kill me… but you have no right to judge me.’ It’s not about guilt. It’s about deliverance from a pure existence whose only meaning is the awareness of that pure horror all around.

What does this have to do with the Russo-Ukrainian War? Actually, a lot. Perhaps, if western analysts understoodthe deep cultural context of what Ukraine was hit with on February 24, then discussions about negotiating with the Kremlin would end. Western Europe needed the bitter experience of the first year of World War II before its politicians could understand that there could be no negotiating with Hitler. It would have been absurd to suggest that Nazis and Jews sit at the same negotiating table – even in a philosophical sense. What values would they start their conversation from? In the eyes of Nazis, Jews were not people and their extermination was a foundation of Nazi policy. For Jews, on the other hand, the Nazis were the personification of absolute evil, incompatible with their own existence. This was an either-or situation, just like in Ukraine, which Moscow is today denying the right to exist.

Wagner’s hammer is the contemporary key to understanding that a system built on the cult of death, of unlimited cruelty, and pure horror is a system doomed to destruction. It is impossible to to come to an agreement with it. It is capable not of compromises, but only short breaks before the new terror. Putin ascended to his throne over the corpses of his political rivals; consequently, he turned his sword also (or, perhaps, above all) against Wagner, who had already wounded him once with their ‘march on Moscow’.

I first encountered Wagner (albeit indirectly) back in 2017, in captivity, when a major from the so-called LNR was thrown into my cell. He had been moved from Luhansk to the Donetsk Izolyatsia, where they were trying to hide him as an important witness to the internal conflict among the occupiers in Luhansk. After a few days of conversations, he revealed that, in 2015, he had fought alongside Wagner commander Dmitrii (Dima) Utkin on the same section of the frontline. When I asked how he’d characterize Wagner, he gave a short answer: ‘It’s best to be friends with Dima.’ As it later turned out, the practice of beheading enemies, burning their bodies, cutting off their limbs and filming the whole thing started for PMC Wagner in Syria and Africa. Back then, this wasn’t intended to become the company’s official doctrine and was still hidden from journalists who, literally piece by piece, gathered evidence of Utkin’s and his men’s war crimes.

After 24 February 2022, everything fundamentally changed. Horror and the Kremlin’s lack of reaction (inability to react?) to it became a powerful promotional campaign for Wagner. That same mountain of tiny chopped-off limbs from Colonel Kurtz’s horror is now being embalmed and put on display for all who wish to see it in the notional museum of contemporary Russia. An exhibition has been made of them.

Ultimately, to use another metaphor, our tram is headed for a wall with a single inscription: ‘Why not?’ This is another question that arose outside of Ukraine and has taken a clear shape for European intellectuals for many centuries. Let us recall Dostoevsky and his ‘if there is no God, everything is permitted’ and, after him, Nietzsche with his reassessment of values. Following the World Wars with their experience of the concentration camps and the mass extermination of people conducted as efficiently as possible, the question of’Why not?’ re-emerges in a new way in Europe, at least on the pages of Sartre and Camus. In The Stranger, Camus’s protagonist asks us, ‘What did it matter that Raymond was as much my friend as Celeste, who was worth a lot more than him? What did it matter that Marie now offered her lips to a new Meursault?’[1]

The question ‘Why not?’ has now been cast down from the heights of scholastic metaphysics to kisses in Algerian neighborhoods. After the extermination of people in the gas chambers and crematoria, the Western logos no longer sees grounds for action in the world: what should a person be guided by if the concentration camps were defeated not by arguments or values but by planes carrying bombs that turned cities like Dresden and Nagasaki into nothingness? The question is then, is this a proposition that gives rise to horror, or its grounds, its foundation, the horror’s direct outcome?

A paradox: the Wagner group mixes the worst of the worst, people from Russia’s social bottom. But sometimes it seems like one of the founders might have in fact read those lines: ‘What did it matter that…’ and come up with their own answer – if it doesn’t matter, then everything is permitted.

Of course, all these thoughts are a foreign language for European towns where an ambulance racing through the city with its sirens on counts as an ‘event.’ This language is impossible to learn – you can only remember it when you’ve lived it. Just like the Baltic states, Poland and Czechia remember it. The same way the Germans used to remember it, especially in the works of their twentieth-century intellectuals, who are now increasingly lost in the deceptive calm of life in modern Russia..

About horror before total Nothingness, Heidegger wrote that people discover themselves in the existence of death, that is, from the perspective that one day ‘I will end’. From time to time, I imagine myself dead and someone quoting from one of my ‘prophetic’ essays such as this one during the funeral. This has become a daily practice in our country: the death of writers, poets and artists whose works are heard for the last time over their coffins. Death has ceased to be a theory and come off the pages into the anti-tank trenches and wailing of sirens.

But Kurtz himself meant with his apocalypse something that’s far from an abstraction: his ‘horror’ was closer to the ‘horror’ of Céline, who gave rise to it through swollen corpses, bomb bursts, human excrement, deep depression against a background of loud laughter, and so on. Journey to the End of the Night showed the horrors of war, but with a tinge of a carnival, where opposites don’t remain apart but get mixed together in a single cauldron.

Here’s what matters: the further the characters in Apocalypse Now go down the river into the jungle, the deeper they sink into themselves and the more their psychological state changes. I believe the director wanted to show the logic of war with this journey into the darkness of the jungle: the longer you’re in it, the more deformed your consciousness becomes. Is there a way back for those who have seen horror? And this isn’t an abstract question. It could be asked of someone specific, or an entire country that will be traumatized by a lasting horror amid its untouched, unharmed European neighbors. It’s likely that there was no way back for people like Colonel Kurtz: whoever merges with the horror of war and produces it themself, must ultimately dissolve in it by dying.

Here, again, it is worth mentioning the French. The writer Jean Cayrol, who survived the horror of the Nazis’ Mauthausen concentration camp, put forward the concept of ‘Lazarus literature,’ which is about the experience of surviving the concentration camps. Cayrol compared people who survived their horrors to the New Testament Lazarus whom Christ raised from the dead. But, for Cayrol, this ‘resurrection’ wasn’t positive, since the ‘resurrected’ can never fully return to normal life, which would entail a certain transcendence of their previous horror. People who have personally experienced horror (not just heard about it from someone else) can never again be ‘themselves’ in the world they are returned to. Psychologically, they are the same as Camus’s ‘stranger’: a lonely, apathetic outsider in the world of the ‘living’. In Cayrol’s opinion, after his resurrection, even Lazarus should have felt some unhappiness and even certain repugnance for the earthly world after experiencing the real transcendence of the afterlife.

Of course, after World War II, practically all of Europe found itself in this state: for a long time, yesterday’s concentration camps, the Gestapo, and frozen or starved children on the streets remained Europeans’ collective everyday reality, and this made them all alike. But, today, the situation is different: for the second year, Ukraine’s collective consciousness is exhuming mass graves and burying children killed by Russian missiles, whereas just beyond Ukraine’s borders the world of the transcendent reigns, wholly incomprehensible to Ukrainians.

But the Ukrainian experience is also a ‘stranger’ to the Italian Riviera or pubs in Prague. After Ukraine’s victory in the war, these experiences will collide. We have still not been accepted into the European Union because of a series of reforms and formalities that we must implement. But no one is thinking about the fact that, after the war, Ukrainians in Europe will feel like Lazarus, strangers incapable of rejoicing at the miracle of getting through the horror.

This is still a long way away. Not only because of the events on the frontline, but also because of the disparity of collective trauma within the country itself. In some places, its depth is equal to the horror of the trenches where you must sleep on enemy corpses for warmth. In other places, people hear about that on TV.

I’m standing in the middle of a sunny plaza in Kyiv. People are gradually coming up from their shelters: the quieting of the sirens brings them back to the heat.

And a tram rattles by…

The ‘War Is… Ukrainian Writers on Living Through Catastrophe’ essay project is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Source link